Read Part 1, here.

When most people sing your praises, consider yourself worthy of none, and when no-one praises and all condemn, that you are worth of much.

Diogenes, Codex Vaticanus Graecus

How vain it is to sit down to write, when you have not stood up to live!

Henry David Thoreau, Journal

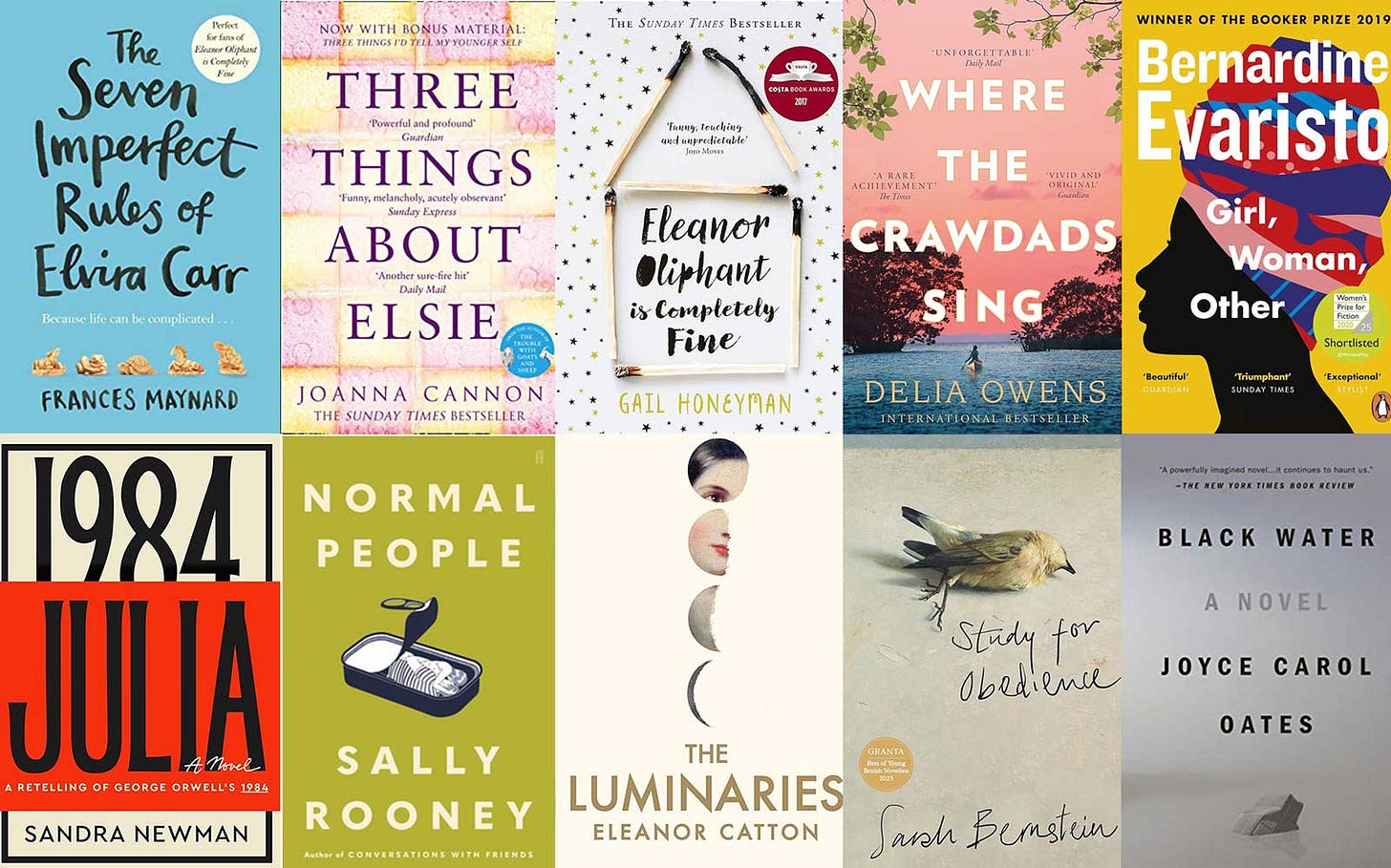

You’d think that the genius and the mediocrity would be easy to tell apart, given that the former gives us finely worked gold and the latter shards of broken plastic, but although time certainly winnows out the chaff, space is considerably less discerning, giving artistic ordure license to travel across the earth before literary magnificence has applied for its passport.1 Discernment has no defence against the popular delusion we call fashion, in this case literary fashion, the fearful need that types have to see themselves reflected in what they read. This is why the ‘powerfully imagined’ works of fiction we see today, clustered with swooning reviews and prestigious literary nominations, find a smooth path to publication, because they reflect the hopes and anxieties of, to take one conspicuous example of a ‘demographic’ that dominates book-buying today, middle-aged, middle-class women.

The reason mediocrities thrive for a time is not because their stories are brilliant, or because their art is transcendent, or because they offer any new insights into human nature, or because their milk-and-water style is anything other than rank dilettantism, or even because they are intelligible. They are read because they are reassuring. They offer, to the reader’s self, the warmth of ‘ah, yes, this is me’. I too am an identity. I too value words above their meaning. I too am a tender and beautiful mother. I too fill the universe with ‘wretched prattle which murderously stifles unconventional ideas in the cot’.2 I too am a disillusioned, nature-loving, ex-professional. I too am emotionally-retarded, functionally-illiterate and can read nothing more challenging than Neil Gaiman, J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling3 children’s books…4

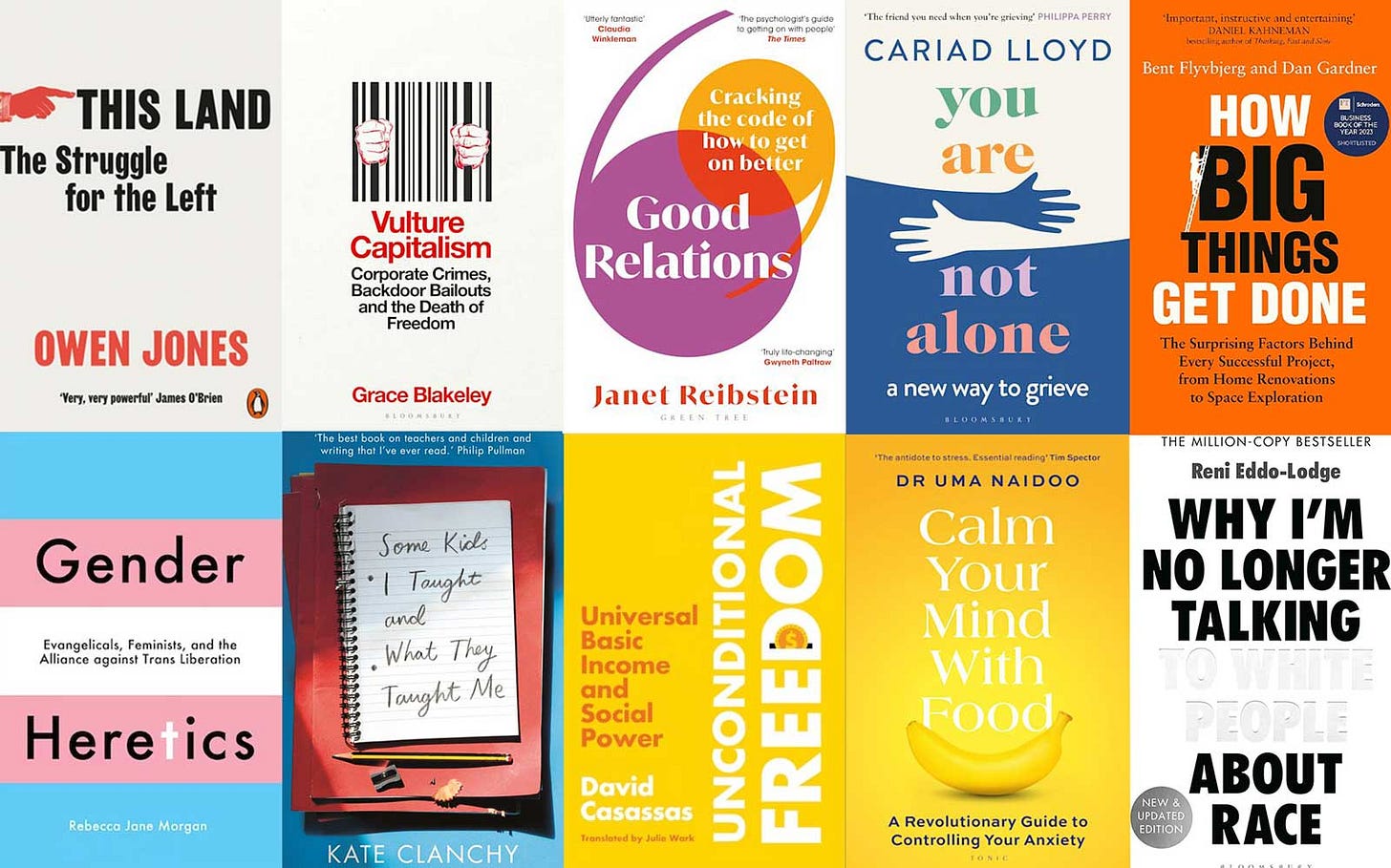

Thus, hard-nosed factual non-fiction which appeals to deeply institutionalised modern minds has no more difficulty locating an agent, a publisher and an Orwell-prize nomination than drippy fiction and experimental literature. Like love at first sight, the institutionalised book consumer senses out her factual allies, just as she does her emotional friends, from titles and covers alone. She wanders into Waterstones, tired after a morning of producing her pop-culture podcast, she sees a big pile of books with titles like Ultra Processed People, or Artwash: Big Oil and the Arts or Memoirs of an Early Arab Feminist or Everything I Know About Love, all enticing to be sure, but her trembling hands land on Calm Your Mind With Food and she thinks to herself, ‘I dunno, the book just spoke to me!’5

I mention professional women not because they are the only people who read books, and certainly not because their taste is any worse than that of professional men, but because they are now in near complete control of the culture industry,6 which explains its ‘hysterically conventional’ nature. Trends come and go, but they speak to the priorities of those who have power over propagating them, which is why there are now so many revisionist stories that substitute male protagonists for female. What happens is this. A young middle-class women,7 attracted to the arts, takes a literature degree, where she studies Hamlet, or 1984, or The Picture of Dorian Gray, or The Iliad. She graduates, works in management for a few years, until she feels rich enough to answer to her calling and write a masterpiece. Hm. But how? What to write about? I know! I’ll rewrite Hamlet as a woman! / Dorian Gray as woman! / 1984 from Julia’s perspective!8 / The Iliad from Briseis’ perspective! To criticise this as ‘sexist’ is as shamefully wrong-headed as questioning the positive discrimination that exalts White Teeth and A Thousand Splendid Suns.

Another favourite, this one employed by both sexes, is to move to the city on Daddy’s dollar, earn a good wage in publishing or media or somesuch, guzzle down some inspiring culture, meet a stable significant other, get ‘burnt out’ and feel cynical about the rat-race, move to a place of extreme natural beauty (where all the locals pretend not to hate you), and then become an elegiac nature writer. Or you can skip the city part and just be born to be a globe-trotting ‘pilgrim’ or a mountain-climbing ‘adventurer’. Throw in a personal tragedy or two, then it’s just a few months tip-tapping away on a sun-drenched glass veranda, or in your cosy rural cottage in Ireland, or Spain, and bingo, a Wainwright-prize-winning classic of raw, emotional, uplifting, triumph.

They just manage words.

Another, less energy-intensive, trick is to wander around your house until you come across something you like, then put your thoughts about it together into an article. The ‘lifestyle’ section of the mainstream press mostly comprises ‘why I like blinds’ or ‘how folding shirts properly changed my life’, but wander a little further afield and, with a bit of research, you can knock out a book-length Wikipedia article about badgers, or graves, or the letter ‘a’, or buttocks, or toilets. Writing books which bend to the religion of technocracy, which sees man’s history as ‘the progress of techniques’9 is a refined version of this, as are, in their way, books solely about books, one of the most futile and spiritually exhausting activities a man or woman can ever engage in; essentially an exalted form of ‘information management’. A fine task for management-minded academics, but the torments of the damned for anyone with blood in his veins.10

Talking of academia, yet another tactic for the wannabe ‘published author’ is to offer a practical guide to getting on in the world—based, of course, on what you have read. It has to be practical, and it has to be based on books alone, and not anything as recherché as actual, unfiltered life, because cultural managers, like the lonely mechanised minds they endeavour to appeal to, don’t really understand life, or have any insight into it, nor do they want to. They are afraid of life. What they want is to get on in the system,11 which means to know how to handle people, know how to ‘manage your emotions’ and know how to ‘be a better person’. The kind of openness to experience, generosity of heart and freedom of thought that being able to live well demands, these are all threats to the management class. They do not want wisdom, they want instruction manuals, and so a million self-help authors are employed to provide them.12

Another popular, if decidedly niche avenue for the writer and ahhtist is to be a professional cynic. This approach is favoured by readers of Emil Cioran, Thomas Bernhard, Fernando Pessoa and similar such authors who write books with titles like Breviary of Chaos or Melancholy of Resistance or Leprosy of Insight. To read and write Important Books about Deep Subjects demands a fear of Anglo-Saxon words, an anxiety about one’s message being seen naked, without the robes of scholarship, extreme conceit founded on bookshelves groaning under the weight of Nietzsche’s collected works and total, pitiless cheerlessness. This kind of tight-lipped hyper-intellectualism rarely finds a publisher,13 unless you’re Jon Fosse, but it is more or less guaranteed an audience of bitterly unhappy over-educated young men who are in love with their alienation (and with extremely difficult books by dead Austrians about that alienation).

I’ll mention one final, rather facile literary fraud that a modern writer can perpetrate with a good chance of being mistaken for meaningfulness; ‘magic realism’14. Thomas Pynchon, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Don DeLillo, Toni Morrison, Zadie Smith, Salmon Rushdie and many, many others have all done very nicely out of parodic characters called Sally-Sally-Sally-Sally, one of a quintuplet of other Sallys, separated at birth, but who all play the Hammond organ, belong to terrorist groups, can speak backwards (etc, etc, etc.) who are then launched into plots roughly as sophisticated as an Egyptian soap opera. Not, as mentioned in part one, that there is anything wrong with magic, or even with melodrama and caricature, but ‘magic realism’ is a misnomer; there nothing real about these books at all, nothing human to tear through the amusing mask. Nothing. Just titillating information.

One might note here that works of magic realism are, like so much Anglo-American fiction today, often presented from an extremely subjectivised third-person view (‘She hated that old washtub, her hands raw an’ achin’ from scrubbin’, mutterin’ under her breath ’bout how it never did nothin’ but make her days longer an’ her back sorer’ — that kind of thing). Such a technique has its value, particularly in shorter fiction where the intimate register is not a constraint, but its limitation is obvious; it cannot touch on universal truths. It cannot achieve any kind of spiritual grandeur or breadth of vision, which is why it is so popular today, and why the ‘authorial omniscient’ point of view, which dips in and out of characters minds but stands above them, is today considered, despite being favoured by the greatest novelists the world has known, at best démodé, unable to take in modern morality, at worst a stamp of fascism.

There are a few other tricks for getting ahead in publishing, not difficult to work out by spending an afternoon in Foyles or reading the New York Times book reviews—if, of course, you are one of the few on earth who possess some literary discernment. Not that you, dear reader, are lacking in that valuable substance. You are well aware that everything currently being published is worthless, but you’d be surprised how many people simply accept that a slickly illustrated book about Captain Ahab’s ex-wife, or how to get decision-makers to say yes in thirty seconds, or the hidden beaches of North Norfolk, or the cultural history of syphilis, or the management secrets of the Eskimos or the ‘wisdom of the Stoics’ wasn’t written by a hollow charlatan with nothing to offer but second-hand platitudes to an audience which cannot bear to read anything else.

Or maybe you wouldn’t? It’s no great revelation that charlatanism sells, that it’s not truth that is rewarded in the world, but the display of it.15 And oh, how wonderful the reward, how gratifying the back-slapping attention; but a secret background feeling of frustration lingers, a distant doubt. Perhaps, perhaps, I’m not as great as all my reviewers are making out…?16 Here we come to the most conspicuous difference between the first-rate writer and all the rest; confidence. All of us are prey to self-doubt, and even the greatest artists, being human, occasionally throw tantrums of uncertainty,17 but rarely. If reading the letters and diaries of great artists teaches us anything it’s that they have almost complete confidence in their powers, while mediocrities are prey to constant attacks of anguished uncertainty, manifesting as stabs of self-doubt in the company of their betters, to whom they inevitably nurture two basic emotions, either fawning adulation, or fear masquerading as haughty resentment.

And why would third-raters be confident? They’ve got nothing to be confident about! More often than not, they are as characterless as the tradesmen (or ‘journalists’18) who hawk their books. Reading through the biographies of celebrated contemporary authors, literary agents, commissioning editors and professional reviewers in the UK produces much the same effect as looking at their faces. What kinds of lives do you think these adventurers of the heart have led? What kind of spirit would you imagine animates their ambition to be involved in literature? You’d expect something of danger and depth, wouldn’t you? Some evidence of a meaningful life, of an inspiring character? At the very least you’d expect some kind of cultural literacy amongst all these men and women of letters. You’d expect them to be very widely read. You’d suppose them to list a great many superb authors and masterpieces of world literature as their inspirations wouldn’t you?

But no. Sorry, no. Their reading is as narrow as their lives. It’s a miracle if they know a second language19, they rarely know their own language very well20 and their culture, insofar as it is encoded in literature, is completely beyond them. Their attitude to culture is that of the average Christian to the Bible or Muslim to the Quran. They believe in it, they follow it, they’ve picked up a few second-hand ideas about it—but they haven’t actually read it, and they certainly haven’t learnt from it. And why should they? Meaning is an ideological hoax.21 There is no need to acquire the culture one pretends to contribute to, or the competence required to do so, because neither culture not competence actually exist, only one’s identification with them—or with their shadow and complement, the postmodern minority-worshipping ideology du jour; inclusionism. This is why those who actually understand their culture—particularly white, male members of the working-class—have as much chance of getting a publishing contract as they do of writing for the BBC or getting an arts council grant.

If culture is remote from the works of second-rate authors, life, as I’ve said, is completely absent. What professional writers know of life amounts to what has happened to them in their families, in their schools, and in their jobs; which is to say, in their institutions. They have never had to face raw existence, and so they neither write about it, or enjoy reading about it. They prefer to read and write books about books. This isn’t to say there is anything wrong with writing literary criticism or allusive parodies or even highly literate exercises in style; the form of all writing is after all, like the very body of the author, made from the bones of those who preceded him. What is so tragically, even nauseatingly, absent from mediocre literature is direct, lived experience. One gets instead observations of the surface of life, its sensual, sumptuous mound of mottled, marble-fleshed form; the appetites filtered through a thesaurus.

All this explains the feeling one often gets from reading the most lavishly praised PMC (professional management caste) literature, that one is not reading work by someone who can write, but by someone who can impersonate writing. One gets the same feeling listening to, say, The Clash or James Blunt, or watching Benedict Cumberbatch or Timothée Chalamet. The professional-management class don’t know what it means to live and to feel, much less to artfully write; all they know is how to impersonate those who do and can. The professional writer is a carefully curated simulacrum which appeals to similarly hollowed out readers, listeners and viewers, perplexed by the bitter revulsion expressed by those who actually do live and feel. And write.

Alongside the lack of feeling, experience, knowledge and confidence of the second-rate writer runs lack of joy in the task, lack of real, passional, interest in the art. Standard, professional writers are not motivated by a need to write, by a something-that-must-be-said burning in their bellies like a hot coal. Consequently, there is no real joy in mastering the means to give this fiery message literary form. This is why one hears, from second and third-rate authors, constant complaints about the difficulty of writing, the effort, oh the pain… Of course it’s painful! It’s painful to swim the channel if you can’t do more than a few laps of the local pool and have no great need to get to the other side. The greats almost never suffer from this, from writer’s block.22 Great sorrow there may well be (‘No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader.’23), indeed a whole vast river of feeling pours through the author as he writes, and there may be fiendish obstacles too—often deliberately placed, by the author, in his own path—and but suffering? at actually writing? Why would you read a book by someone who did not enjoy writing it? You’re as likely to find joy there as you are in the company of someone raised by parents who hate children.

Uncertainty and lack of love in the act combine to create another notable feature of mediocre writers, their need for recognition. Naturally, all artists love (and deserve) applause,24 but if they need it, it can only mean that the work itself is not sufficient. The genius, unlike the second-rater, does not need other people to tell him his work is great. He knows he is producing quality, and he loves to do so, even if nobody ever reads it. The mediocrity, by contrast, is pathetically dependent on a large readership, or even a modest one, or on agents and reviewers telling her that her work is brilliant, moving, profound, whip-smart, and so on, or even, most pathetically, on the contrived enthusiasms of friends and family.25 Success of course is a wonderful sedative, smothering self-doubt, but sooner or later it wears off

This explains yet another notable quality, or lack thereof, in writers who cannot produce good work. The fact that they would actually be just as happy doing something else with their lives. They love to tell themselves that they simply OMG must write, but the reality is, they’d get along quite happily if they had to live by some other, equally congenial, means. True writers, like true actors and musicians, simply cannot live any other way, as the fact that they continue writing through real hardship (not to mention constant rejection) testifies. They will go to absurd lengths to keep doing what they are doing, and make almost preposterous sacrifices; even, finally, of their lives. What will the best-seller risk? What will the hobbyist put on the line? What will the prize winner sacrifice?

This is why literary mediocrities slip so effortlessly from restaurant management to theatre management to academic management, for the simple reason that they are all managers. They don’t actually do, or create, anything; they just manage words. The fashionable writer simply reconfigures what he or she has read, or remembers, or can imagine. She has no real sensitivity to the truth of life, and so no real ability to express that truth. Again, the alienated middle-class reader, whose life is spent fussing over how to manage her money, her property, her family, her career, her mind or her emotions, sees no problem here. She welcomes a series of well-curated, second-hand ideas like an old friend. She loves galleries, you see, and museums, and gardens, and everything which speaks the language of management, provided that it is smoothed over with sentiment, nostalgia or enigmatic absence, so that the horrific reality underneath her tidy world will never push itself into consciousness.

Majesty does not live in a tidy manner. Compare the heroic biographies of great writers with those of the celebrated writers of today, or indeed of any day. Take a look at the profiles of Hot New Names, or read through the backgrounds of Nobel, Booker and Pulitzer prize winners, or examine the life stories of edgy radicals.26 They’re keen to wave around their credentials as outcasts, to humblebrag about the gruelling challenges they’ve overcome, because they well know that great writing demands a heavy pounding from the unsentimental fists of a difficult life, but look carefully and you’ll see that most of them have been very comfortable, thank you very much, in a cosy, dependable middle-class home27 and professional career, with a well-feathered parent or two (or their inheritance money) to fall back on if the crazy expedition to Iceland, the experimental punk band or the mad socialist sock startup doesn’t pan out.28

The lack of experience of professional writers explains the necessary pose of radical critique that so many of them, on the left and on the right, adopt, and in a sense must adopt. In an age such as ours, of dissolution, fragmentation and technolatrous abstraction, everyone is an ironic spectator, watching the performance of society-on-the-screen and gaining meaning and identity from the pose. Pull up the cover of this radical posturing and one finds no artistic truth, no surprising revelation, no salty aphorism, no memorable metaphor. Just facts and recommendations which stand in relation to true rebellion as complaints about the way a prison is run stand to freedom from it, or burning the thing down.29 But freedom is impossible in the present age, as the prisoners themselves are as dissolute, fragmented and abstracted as the prison itself. They exist under the same conditions as their confinement and so cannot conceive of freedom from it. It thus becomes impossible for such writers to have truly original ideas, because there is nothing inside that can recognise them. As Cyril Connolly noted, ‘A comfortable person can seldom follow up an original idea any further than a London pigeon can fly.’ They may, in their midnight hours, stumble across a gem, but in the darkness, it looks like a pebble.

Which brings us to one of the most depressing traits of the literary mediocrity, lack of humour. If you try and pitch a comedy to literary publishers and agents, they will tell you that ‘humour doesn’t sell’, which is a strange thing to say, on the face of it, when just about every masterpiece of world literature was either a comedy (before the modern era, practically all novels were comedies) or sparkling with humour, when even the darkest or most difficult authors can raise a laugh; Schopenhauer, for example, Goethe,30 Dostoevsky, Proust, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Orwell, Dick… all the greatest authors have a sense of humour, a silliness to their spirit, even Wittgenstein and Kafka.31

The reason that publishers and agents don’t look for humour, when the greatest writers (and directors and actors and musicians) all have it, and when everyone else in the world values it so highly, is because they, publishers and agents, do not know what it is. Cultural managers and professional-class writers and ‘artists’ lack the bawdy physicality of good humour, they lack the innocence that comic charm possesses—the personal exposure and honesty of people who are genuinely funny—and they lack the ability to perceive true paradox that great wit demands. They have none of that, which is why they are so boring, why their attempts at humour are harsh, stale, sadistic, vacuous, witless, dry and forced, and why they create and commission works of art that drain the life-force from anyone acquainted with wild joy and passionate love.

And here we come to the final, most terrible, handicap of the literary mediocrity, his lack of love. The reason celebrated writers say nothing to nobody is not, ultimately, because they cannot write, it is because they cannot love; and so they cannot be loved. Superficial writers and readers might — it’s unlikely, but they might — enjoy P.K.Dick‘s ‘imagination’, or Lawrence’s ‘sensuality’, or Dostoevsky’s ‘insight’ or Dickens’ ‘comedy’, or Shakespeare’s ‘poetry’ but they have no idea why these writers are infinitely superior to their contemporaries, and why their work endures. It is because the author is supremely, pre-eminently loveable — a word that the mediocre mind cannot distinguish from being merely likeable. Likeable authors (and broadcasters and journalists and so on) are popular because they do not love. Great authors are immortal because they do.

Conclusion: In the Temple

Søren Kierkegaard complained that his own literary culture was so willing to accept second-hand opinions that a book could be published, reviewed, and cause a sensation without having actually been written. Now we find ourselves in a world in which it is quite possible that none of it is being written. How do you know that any of the recently-published books you read now were not written by a sophisticated chat-bot? You don’t—because nearly all of them were. Perhaps not by an artificial language-generator, but at least by the second-hand, second-rate automaton that sits in the head of the celebrated writer.

If it were any other way, he or she would not have succeeded. The position of the great writer in the system, particularly in a corrupt and decadent system such as ours, is not much different to the position of anyone else with spirit, dignity, intelligence and a loving heart, in that such qualities can only be preserved at the expense of one’s position. The more spirit, dignity, intelligence and love you have, the more in danger you are of losing your job. Ergo, writers who make it through their career without having been ignored, banned, fired or demoted are unlikely to be saying anything worth reading.

This is true everywhere. Take a look at the most successful and secure doctors you know, or councillors, or roofers, or call centre operatives, or that most depressingly cultureless class of mediocrities, the small-minded ‘henchmen of the state’32 we call teachers. While the decaying system does allow a certain amount of laxity, goofing off and buggering around, generally speaking, anyone who is doing a good job—anyone who is taking their time, is generous with their resources, is unwilling to compromise and is committed to the truth—won’t keep their jobs for very long at all.

And so it is with writers. The task of the writer is (albeit indirectly) to expose lies and injustice, so they cannot hope to succeed in an immoral system, which cannot stand to be exposed. The task of the writer is to change language so that it better expresses meaning, so they cannot hope to succeed in a meaningless system, which relies on received, rigidly defined concepts. The task of the writer is to pursue original truth beyond artificial and arbitrary boundaries, so they cannot hope to succeed in a system which demands predictable standardisation. The task of the writer is to say meaningful things, so they cannot hope to succeed in a system which only rewards, and only can reward, the appearance of meaning.33 The task of task of the writer is love so passionately that life unmasks herself, so they cannot hope to succeed in a world which only honours the appearance of love.

Thus, those writers who do succeed cannot show you the nature of the self and system as they actually are. If a writer is to be successful, she must not experience too widely, or too deeply, or learn too much, or she is liable to find herself outside the prescribed limits of acceptable thought. Only if one can demonstrate that one is aware of these limits, and will not reach beyond them, can fame and honour be granted. Thus, the almost unbelievable uniformity of expressed thought amongst the rich, the famous and the professionally at-ease on matters of importance. While merely famous writers (actors, comedians, journalists, etc.) never offer an opinion which jeopardises their careers, great writers bite nearly every hand that feeds them.

The limited depth and experience of the cultural elite helps explain why sales figures from large publishing companies are so low. Although the findings from the recent Penguin Random House / Simon & Schuster merger trial were misunderstood,34 they highlighted that the so-called ‘mid-list’ that once made up most publishing revenue — and where all the best books could once be found — has given way to blockbusters at the top end, and a thousand books about white privilege, caring for kestrels and facing menopause at the bottom. The reason why is simple. It’s all written, both for and by a management class which prides itself on being unlike most of the planet, more specifically, unlike the working class, and so has no idea what those people (or rather ‘those people’) will really enjoy reading. Insofar as the perceptions, instincts, insights and values of those people threaten the management class, any books that they either write or want to read brings on, in publishing agents and commissioning editors, a bout of existential nausea which they are compelled to interpret as fineness of sensibility and delicacy of constitution.

This is why great writers today cannot get anywhere with agents and publishers,35 why they are ignored by their peers, and why mediocrities are honoured and praised. What’s more, as with all other postmodern institutions, the cultural industry doesn’t just promote decision-makers without taste but, as any kind of competence is a threat and an irrelevance, filtered out by a professional system which rewards money, connections, cultural capital and toadying to official totems, it more or less guarantees that editors and agents cannot carry out the elementary tasks of publishing. Authors find themselves ghosted by agents, even after months of rewrites, forgotten by editors, who have rarely read their book or do not understand it, and promoted by teams whose priorities have nothing to do with selling good books. A well-read publisher, genuinely interested in literature and in authors who produce it, is as rare as a moral lawyer, a healthy doctor or a sane psychologist.

Although we live in conspicuously decadent times, all this has long been the case,36 for genius is the worse crime anyone, artist or otherwise, can commit against those who stand guard over culture; the academics, reviewers, publishers, priests, princes and agents who determine whether work will be recognised. Nothing, but nothing, is as offensive to civilised people as artistic truth, originality of conception and the passion that brings it forth. Penetration of perception, freedom of thought, vivid intensity and essential, uncynical beauty fill the hearts of culture-makers, and most of their reading audience, with fear and disgust, which they blame the writer for. Only when he is dead, and his genius can be safely appreciated, does he gain the recognition he is due.

Conversely, when fashionable, award-winning authors die, or when the fashion that sustained them moves on, their mediocrity becomes clear and they vanish, sometimes overnight.37 Who will remember the famous and honoured writers of our day, those with huge follower counts on social media, weighed down with prestigious awards? In a few years Salmon Rushdie, Douglas Stuart, Anna Burns, Bernardine Evaristo, Gillian Flynn, E.L. James and Paula Hawkins will be as well remembered and honoured as Florence L. Barclay, Cecil Thurston, Gene Stratton-Porter, Jeffrey Farnol, Booth Tarkington and Zane Grey. Who are they? The famous and honoured authors of one hundred years ago, all now unknown.38 As Jean le Rond d’Alembert taught us; ‘The interior of The Temple is inhabited by none but the dead who were not there while alive, and a few living most of whom will be thrown out after they die.’

Part One…

Further Reading…

Which is one reason greatness has such a hard time doing business with publishers, producers, gallery owners and the like, because, when it appears, it’s never a very good investment.

J.K. Huysmans, Against Nature.

I read Tolkien and Gaiman when I was a young man and enjoyed both, and I hear that the Harry Potter series is very entertaining too — and what’s wrong with that? Nothing at all, unless that’s as far as your reading goes.

More subtle than the self’s surface need to see its trivial concerns reflected back at it is, but more profound, is an intuitive demand to have its status as a thing confirmed in art. This takes two apparently divergent forms which, like so much of worldly life, turn out to be the same illusion under different aspects. I am referring to the need of the isolated mind to constantly absorb rational facts, and of the self-bound heart to constantly absorb irrational facts. The practical, hard-headed man of science demands a constant diet of objectively true things in his literature, while the emotional, soft-bellied woman of art demands non-stop subjectivist impressionistic things when she reads. Supply either of them with a truth which supersedes both fact and emotion, and you will get nowhere. Or, to put that another way all work which transcends objectivity and subjectivity is instinctively rejected by objectivists and subjectivists, who then see each other in it.

Previous winners of Orwell prizes include (oh George, avert thine eyes) Suzanne Moore, John Harris, Peter Hitchens, George Monbiot, Polly Toynbee, David Aaronovitch and… Carole Cadwalladr!

Men, particularly white working-class men, have a rough time getting published in an industry comprising 80% women. Literary men — and by ‘men’ I mean masculine men, not effete hanky-wavers — are as rare in the publishing world as working-class men are in parliament, for the simple reason that success in literature is not earnt, but given; to women who produce lightly decorated smut, second-rate wish-fulfilment (‘romantasy’), ‘beach reads’, ‘wellness thrillers’ and ‘post-apocalyptic chick-lit-lite’.

Or aspirant to the middle-class.

I am referring to censorship-enthusiast Sandra Newman’s best-selling blockbuster Julia, a poorly-written, melodramatic rectification of 1984, which presents the case, over and over again, that Winston Smith — not to mention Orwell — is a racist, misogynist bore and Oceania really isn’t all that bad. As you might expect from a work of bourgeois fiction, it is optimistic about living in dystopian society (as the publisher’s press release notes Julia ‘understands the world of Oceania far better than Winston and is essentially happy with her life’), it is upbeat about all the terribly people of colour she meets and, of course, it has a happy ending!

Man reconstructs his history in terms of technology… It is no longer a history of great heroes, of wars, of charismas and gods. It is a history built up little by little on the progress of techniques.

Jacques Ellul, The New Demons

Obviously there are great and even urgently necessary books of literary criticism out there. Very few, but they certainly exist. I am speaking here generally.

Either the formal ‘mainstream’ system, or a fringe online version of it.

I’m thinking not just of Lose Weight in Five Minutes and How to Make Money With Your Immortal Spirit but more refined self-management books, the kind written by Malcolm Gladwell, Mark Manson, Jordan Peterson and so on.

One of the biggest selling books of recent years, you might have heard of it, is a highfalutin self-help book called The 48 Laws Of Power, by Robert Greene, with chapters such as ‘learn to keep people dependent on you’ and ‘pose as a friend, work as a spy.’ Greene quotes the foulest ideas of Nietzsche against a pomo straw man, while unironically warning us to ‘beware’ of people who do not wish to play power games. Not that people who say they seek ‘equality’ aren’t dangerous, nor that it isn’t important to possess and learn how to use power, nor even that the advice in the book isn’t useful, it is, a little; but largely as a weapon against vicious cynics like Greene.

Although that may change in the future.

Or, as James Wood correctly terms it, ‘hysterical realism’. There is nothing wrong with magic in a story, even outrageous fantasy, but these must be grounded in the still, simple reality of the human heart, and in the salt-in-the-eye realities of actual life in this dread world, or they are simply pornographic.

As Schopenhauer constantly reminds us.

‘Imposter syndrome’ they call this nowadays. If you suffer from this modern malady chances are you actually are an imposter. Go home.

Particularly actors, whose spiritually-demanding job brings on terrible attacks of self-doubt—although even then we tend to find it is actors who cannot act—cannot listen, or be affected by what they hear—who are most anxious (and who use ‘acting’ to cover their fears). In literature, music and painting, one rarely finds insecurity in a mature artist. Michelangelo wrote to a friend ‘my painting is dead… I am not a painter,’ but even this letter has an air of Italian theatricality about it. He doesn’t sound serious.

A great many bad writers make their whole living by that foolish mania of the public for reading nothing but what has just been printed, — journalists, I mean. Truly, a most appropriate name. In plain language it is journeymen, day-labourers!

Arthur Schopenhauer, On Authorship

Anyone who doesn’t know foreign languages knows nothing of his own.

Goethe, Art and Antiquity.

How many writers know what a relative clause is, or a transitive verb, or understand the difference between a gerund and a present participle? They usually give the feeble excuse that they weren’t taught in school!

‘…designed precisely to keep people from questioning it’. James Wood, The Broken Estate.

Or not until they’ve written themselves out, which takes fifteen to twenty years. The only great writers I am aware of who mentioned the effort of writing while they were in their pomp, and then only once or twice, were Hemingway (who was not after all very great), Kafka (who complained about everything) and Orwell. I know of no such complaints from pre twentieth-century authors, except Flaubert, who hated writing, hated his characters and hated life—and therefore produced hateful books.

One might also note here the mind-boggling fecundity of the greats. Are we to suppose that, say, Lawrence (who died at 44) wrote 600 works across multiple genres, or that Charles Dickens wrote fifteen colossal novels, or Chekhov 568 stories, or Kierkegaard 38 weighty books, or Shakespeare 38 immortal plays, or Aristotle 200 treatises, or Balzac (a superhuman) eight million words, all huffing and puffing and praying for the agony to stop?

Robert Frost, Preface to Collected Poems.

And appreciate (and deserve) money. Not paying a writer (or musician or artist) for his work is like not paying your baker for his bread. In this world it is unethical.

To whom one should, if one can help it, avoid showing one’s work, unless the writer should happen to have, among his friends and family, someone who stands far enough outside of society to recognise greatness. If, as French philosopher Jean Rostand, reminds us, ‘literature is proclaiming in front of everyone what one is careful to conceal from one’s immediate circle,’ then mediocrity is proclaiming to one’s immediate circle what one cannot or will not proclaim to the world.

Sally Rooney ‘worked as a restaurant administrator before publishing her first book at the age of 26’, Jon Fosse ‘worked as a journalist, graduated with an M.A. in comparative literature and published his first novel at the age of 24’, Slavoj Žižek’s father Jože ‘was an economist and civil servant from the region of Prekmurje in eastern Slovenia. His mother Vesna, a native of the Gorizia Hills in the Slovenian Littoral, was an accountant in a state enterprise.’

Physically warm that is.

Not that, I should add, great uncertainty and a gruelling slog through existence make for great art. If that were true half the world, the bottom half, would be writing Hamlets and sculpting Davids. The writer, like all artists, must bring certain personal qualities, above all conscious sensitivity, to his life, but it is striking, reading biographies of the very greatest among them, how rich that life turns out to be.

Why are our public intellectuals so tedious, narrow-minded and dull-witted? Think of the big thinkers of our times, the ‘intellectuals’ — David Graeber, Jordan Peterson, Noam Chomsky, Sam Harris, Steven Pinker, Slavoj Žižek, Richard Dawkins, Seven Fry, Yuval Noah Harari (to say nothing of small fry like Daniel Pinchbeck, Paul Kingsnorth, John Steppling, C.J.Hopkins and forty thousand Substack intellectuals sweating away to produce literature). If literate civilisation were to continue another seventy years, which is almost impossible, certainly not at anything beyond the medieval scale, all of these mediocrities and charlatans would be lucky to find themselves as footnotes in the history of ideas. Why? Because they have all been elevated into position by the bourgeoisie, a group of people whose values and tastes amount to little more than equality, which is to say, to bringing people down to their petty level. Great thinkers annoy them. They have no need of their ideas, nor any real desire to engage with them. The thought of past masters, as well the work elevated minds of recent times, is useless to the professional management class.

Worth noting Goethe’s warning though;

Humour is one of the elements of genius—admirable as an adjunct; but as soon as it becomes dominant, only a surrogate for genius.

Goethe, Art and Antiquity.

But then these people are all Old White Men, and so incapable of creating anything meaningful. This is why they are gradually being ushered off the cultural stage. Shakespeare? Dickens? Dostoevsky? Lawrence? All misogynist, racist, heteronormative bigots.

Thomas Bernhard. Referenced elsewhere in this essay disparagingly, but, like Cioran, no fool. Many of his aphorisms are excellent.

This is one reason why ChatGPT can never write a novel worth reading; it cannot intend, and so it cannot produce meaning. The other reason being, as Ted Chiang points out, that AI-produced art can only ever be an over-simplified form of plagiarism that smooths out the thousands upon thousands of artistic choices a novelist makes in the course of writing.

Contrary to the viral claim that ‘50% of books sell fewer than 12 copies,’ trial data revealed only 14.7% of titles from major publishers (PRH, S&S, etc.) sold under 12 print copies annually (and this didn’t include ebooks), while 51.4% sold 12–999 copies. Still surprisingly low numbers.

I think they are stupid to even try. Notwithstanding a freakish stroke of luck, success guarantees failure.

As Dostoyevsky notes, in The Devils…

…all these talented gentlemen of the middling sort who are sometimes in their lifetime accepted almost as geniuses, pass out of memory quite suddenly and without a trace when they die, and what’s more, it often happens that even during their lifetime, as soon as a new generation grows up and takes the place of the one in which they have flourished, they are forgotten and neglected by everyone in an incredibly short time.

And just as those who were never really writers but who achieve success are forgotten the moment they die, so, if they do not achieve success, they themselves forget that they ever really wanted to write…

I am sure that some are born to write as trees are born to bear leaves: for these, writing is a necessary mode of their own development. If the impulse to write survives the hope of success, then one is among these. If not, then the impulse was a best only pardonable vanity, and it will certainly disappear when the hope is withdrawn.

C.S. Lewis, Letter to Arthur Greaves.

Even the best-selling lists for the 1970s are full of nobodies.