The Myth of Culture

Why our cultural world is a wasteland

The system’s cultural industry suppresses originality; both individual creativity, or genius, and collective creativity, or scenius · · · It does this because genius and scenius both come from outside of the system, and therefore cannot be controlled, categorised, or packaged by it · · · Suppression of genius and scenius occur through the automatic, unconscious activity of technology and of the market, which prevent people from accessing their own society, and the ego, which prevents people from accessing their own consciousness.

‘Innovative’ and ‘new’ are two of the most used words in the system’s lexicon, but, as with ‘growth’, ‘freedom’, ‘democratic’ and ‘newsworthy’ innovative only really counts as innovative if it serves the system, which seeks new answers to one question only; how to accumulate more capital.1 New ways to extract more work from labour, new technologies to increase production, manage consumption, or suppress dissent, new methods to fix people into the system, new inducements to buy more, new techniques of generating profits, new products, new markets and new marketing campaigns all represent the needs of the system and therefore the acceptable direction of innovation.

The nature of the limits to systemic innovation is exposed in the contradiction that exists between ‘innovation’ and ‘risk’. In the literature of the system, the word ‘risk’ always refers to minimising risk to the lowest possible levels, thereby ‘maximising return on investment’. Anything which cannot be predicted or controlled—creative inspiration, autonomous choice and all spontaneous natural and social processes—represents an enormous threat to the system and must be, at all costs, restrained or controlled. This is either achieved through direct compulsion—which is why capitalists always seek to control governments, which can indemnify risk and control those who upset capital by not paying their rents or turning up for work—or through indirect influence—by reshaping the environment2 to funnel awareness towards its priorities, forcing activity down canalised, controllable and, as it were, socialist pathways. Genuinely free choice, inspiration, life itself, must be induced, only under such conditions is the system prepared to allow ‘risks’ in a ‘free’ market.

Annihilating the threat of uncertainty results in the endlessly expanding technological system, the proliferating omni-identical suburban death-zone we term the town (and, especially, the suburbs), the monocultural agricultural wasteland, devoid of free, natural life, we call the country, and the predictable sameness of all graduates, professionals, jobs, schools, films, books, songs and newspaper columns; in short, the death of nature and the death of culture. Only such a monoworld (a.k.a. the interzone), one in which all components are comprehensible, predictable, controllable and interchangeable, is acceptable to the system. More of such a world counts as ‘innovative’ or ‘new’, less—no matter how original, useful, vivid or beautiful—is automatically rejected.

The rejection of originality, truth, creativity and so on is not a personal, explicit, focused activity, but a systemic output. Collective originality (a.k.a. ‘scenius’) is automatically suffocated by time-scarcity, absence of conviviality, digitisation of experience and other consequences of the expansion of the system into the cultural realm, which forces artists to depend upon the machinery of the system to realise their work. The culture industry in turn judges art by how suitable it is for the system, pouring its energy into ensuring that system-friendly titles will be successful. This premium on market success means that art cannot be produced that will antagonise any class, stratum, geographical or religious section of the prospective readership. Murder and mayhem are fine, as is a little bit of controversy, but the serious suggestion, for example, that religion, scientism, feminism, capitalism, communism, nationalism, professionalism, sexism, consumption, mental illness, democracy or communications technology are bobbins will not sell, and so cannot be produced. Genuinely radical social criticism, which concentrates on laying bare the roots of social evils, is taboo among all publishers, producers and critics (‘too incendiary, too controversial, too angry’ or perhaps, ‘cliched’), as is any work which crosses genres (‘falls between two stools’) as is any song, novel, film or work of art which expresses the nature of human life, as opposed to its systemic appearance and priorities (‘I like it, but I’m afraid I won’t be able to sell it’), as is any work that meaningfully suggests there might be a natural, social or existential reality beyond the self (‘I didn’t understand it’ or ‘it didn’t speak to me’).

There is nothing like a recognisable social reality in system fiction. When it does appear it has the strangeness of an alien world. In fact alien worlds usually seem more familiar to readers and viewers. In the art of the system, man scarcely lives in a social world at all. Or a natural one. Ponderous imitation of nature is permitted, as is the sickening relativist sentiment of green and neo-green doomers, but the essence of natural majesty or harmony in artistic form is as rare in painting and literature as the wild is in society, and greeted with the same incomprehension.

Market priorities, and the intense conservatism of the cultural industry, also demand that preference is automatically given to producers of culture (authors, artists, musicians, etc.) whose fame or whose imitation of other successful cultural products, provides advance assurance of a large market. Over time, Big Names dominate the mass-media in the same way that huge corporations dominate the mass-market, no matter how mediocre or meaningless their output.

Rebels do not question it and even talking hot-dogs unthinkingly submit to it.

Another pressure on cultural scenius is the destruction of the society from which it naturally arises. Massively inflated land prices3 drive up the cost of living, which prices out the free time required to make great art. And just as gentrification forces up rents in the physical world, so the ‘gentrification of the arts’ excludes poorer people and the working classes, who have neither the time nor the connections to enter public broadcasting or gain access to the means of artistic production4; not to mention understand their own cultural tradition or the reality its greatest contributors endeavoured to express.

This is why internet on the beach, pianos at school, William Morris graffiti, Ozu on teevee, Beethoven’s seventh on the London to Brighton or any other kind of ‘democratisation’ of the arts are all next to useless. Consumers of entertainment are supine before neoliberal ‘creative industries’ which have completely colonised cultural life, replacing meaning with novelty, technological ‘innovation’, ‘diversity’, and other market-friendly ideological instruments, which are then taken to be culture; anything else feeling ‘weird’, or ‘boring’, or ‘offensive’, or ‘hopelessly out of date’. In addition, such consumers are harried, stressed, lonely, working all day at meaningless tasks for the enrichment of others, living in ugly accommodation owned by others or bamboozled by a lifetime of emotional overstimulation, hyper abstraction, sensory deprivation, alienation, advertising or grinding poverty. Under such circumstances the eternal truth and apocalyptic beauty of great art and wild nature, their revolutionary harmony, subtlety and power, have either been co-opted, or they cannot be perceived at all. The organs to do so have withered; and even when the problem is grasped or the solution glimpsed, the energy required to do something about them, much less create enduring works of beauty oneself, is absent. Most people do not know what to do with free time and when it appears they feel only an anxious need to consume corporate fun or, at best, cultural familiarity. This is also why media reform is, ultimately, useless.

Talking of familiarity, it is worth pointing out the cultural ruin that peer orientation has resulted in. Culture is no longer handed down ‘vertically’ from adults to children, but is now only passed ‘horizontally’. It can of course be a very good thing for children to reject the values of their elders, but for the young to break entirely with adults, to reject tradition completely—to dress, think, talk and act like other children—is a social disaster. The young no longer seek to express themselves through the long-evolved scenius of their cultures but through the tastes and preferences generated by cliques. That these are sterile and degraded is putting it mildly. Just take a look at the cultural icons of the youth—happily provided by corporate power—to get an idea of how far we have fallen in just forty years. And it will get much worse.

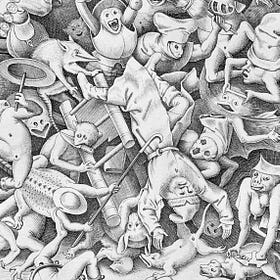

The final, and one of the most catastrophic means by which scenius is degraded and banished, is the curtailment of play. Children have no opportunity to play outside of artificial, mind-made, intensely managed institutional or virtual environments. And nor do adults. Joyous laughter, ‘inappropriate’ language, satire and uncensored play are banned in all workplaces everywhere, supplanted by ‘fun days’, ‘informal working spaces’, ‘bonding exercises’, ‘jolly good fellows’ and other market-friendly morale-boosters. Non-work play usually amounts to intoxication, competition or passive consumption of fun. Free cooperative creation, unmanaged joy and psychologically liberating ritual—the living foundation of collective genius—are now so far from most people’s experience that there is no need for centralised authority to bust the party; general awkwardness, apathy, confusion and the uptight distaste of the internal censor are far more effective police. We do not need the authorities to direct our behaviour when we have an inner voice which tells us that spending free time on anything but enhancing employability is frivolous ditz, that playing with other people’s children is tantamount to paedophilia, that spending a weekend engaged in improvised theatre in the forest is ‘not my thing’ or that being silly will expose you. Such instructions cut subversion off at the root, and with it subversively original culture.

The result of all these pressures is that almost nothing by way of genuine living culture5 is now fed into those most in need of it, the poorer classes, who are overwhelmed by mass produced pap which, in lieu of their own direct experience of reality, they tend to reproduce in their shoddy and superficial artistic output; an omnipresent pornography which deadens the souls of a great many young men who would otherwise have been sanely wanking their guitars.

When ordinary people no longer hang out together, jam and idle, when they no longer have access to creative resources, when they are priced out of their own neighbourhoods, and when they are as far from the wild, and from a dignified, natural life within it, as it is possible to be, a self-reinforcing cycle of cultural degradation takes hold, whereby only the most mediocre (albeit technically competent) painters, producers, directors, musicians and writers can afford to produce art and gain an influence over culture; which they inevitably use to expand the reach of second, third and fourth-rate work, which, in turn, conditions artists no longer able to create beauty, into believing that the word ‘genius’ refers to hairdressing, phone manufacture, burger recipes, graphic design, digital effects saturated fight sequences, luxury porn, literary characters that sound like middle-class graduates, reboots, hyper-bland aural pap, bleak, titillating or ‘ironic’ modern art, modern artists that look, sound and behave like upper-managers, hip-hop, superheroes, rich kids with deep voices who can do impressions taking the place of actors and oceans upon oceans of pornoid mediocrity.

We have lived in such a cultural wasteland since the 1990s (although the death-blow was delivered at the beginning of the 80s). Since then, joy has given way to mere excitement, surreality to mere randomness, vividness to mere intensity and the superb insane strangeness of free comedy has given way to the witless sniggering of bourgeois ‘comedy’.6 The difference can no longer be detected because artists no longer have access to a reality which forces them to discern it. Those who would create the art we need are isolated from the harmony of lived nature and genuine culture, and can no longer detect its presence. Cultural ugliness and aesthetic squalor colonise the earth and come to seem normal, until the building of a great work of art comes to be as difficult, and as unlikely, as the building of a cathedral, while those who look back with longing at the cathedrals we once built appear hopelessly out-of-date.

Thus the control of cultural output and the control of the multitude from whence it must arise, go hand-in-technological-glove. The freedom of ordinary people to produce original works of art or culture is intolerable to power, which must convert their lives into commodities and then counter the effects of the resulting misery with a pacifying spectacle of fun and authoritarian normality, bonding the population to the status quo by endlessly promoting or reproducing those ideas and ways of life which serve both it, and the ego which feeds it.7

This time-bound (or fashionable) ego has always been8 inimical to great art or to any kind of meaningful advancement in human knowledge; the output, that is to say, of genius, the timeless, natural, intelligence of life that great people empty themselves out to host. Ego, feeding off the intellectual, moral and aesthetic fashions of the group, and beyond that the system, that it huddles to for warmth, is terrified by anything which gestures to a reality beyond what it knows, and what it feels it knows. The unknown—originality, that is—always greets the ego as an incompatible known, which is to say, as some kind of violence, threat, offence, or some other kind of devil. It is instructive, in this regard, to read of the lives of Jesus of Nazareth, Shakespeare,9 Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, Monet, Dostoevsky, Van Gogh, William Blake, J.M.W. Turner, Herman Melville, D.H. Lawrence and Nietzsche; all of whom were rejected by those around them, passed in and out of fashion, and struggled for money, and all of whose works are now in the hands of critics, curators, auctioneers and other bourgeois guardians of culture; the dust people who haunt classical music recitals and fine art retrospectives.10

Ego will do everything in its power to protect itself against the reality that genius represents; if that reality has the chance to get anywhere close to awareness. The unquenchable thirst that ego has for reflections of its own beliefs, desires and fears is enough to drive it away from genius and into the mountains of meaningless drivel (or meaningless doughnuts) that it consumes for reassurance. This reassurance it calls ‘pleasure’, ‘fun’ or, if the object is that of a now safely dead, system-subsumed artist, ‘appreciation’. Serious engagement with living genius and profound expressions of the inner life of the individual (as opposed to the mass or minority type) bores, offends, confuses, annoys and horrifies ego, which does whatever it takes to make sure that it does not get in the way of its self.

This is the essence of cultural life in a late-capitalist or Huxleyan system, which doesn’t promote ideologies, or force explicit propaganda upon a captive audience, but automatically promotes submissive, ego-driven people, who automatically take their thoughts and desires to be reality, into positions of cultural power, providing them with a platform to endlessly—‘freely’—duplicate stereotypical behaviours, established social roles and reassuring, ego-friendly cultural ordure. Books and films about the history of the spoon, or how to calm your mind with bananas, or Moby Dick with a lesbian Ahab, or biopics about rock stars, scientists and other businessmen (rise to fame, fall from grace, return as low-grade caricature of former self), mashed up multiverses in which Beethoven does battle with Darth Vader, and all the ideological puppet shows of the postmodern screen blend seamlessly into the puppet show of the postmodern life.

The unhappy, stressed, ambitious, insensitive and psychologically imprisoned teacher, shop assistant or factory worker finishes work in order to consume entertainment in which a world of unhappy, stressed, ambitious, insensitive and psychologically imprisoned teachers, shop assistants and factory workers is either normal or given a flavour of paradise. Even cartoons set in the afterlife, fantasy epics set in alternate realities and dystopian sci-fi of the year 3500 must exalt intense specialisation, alienating commerce, infantile technophilia, meaningless or coercive bureaucracy, rigid hierarchies, scientism, relativism, self-obsession, tense emotionality, specious literalism, restless desire, hyper-rationalism, reassuring groupthink and the denial of life. You may, indeed you must, resist enemies within the given world (even, and ideally, ‘The Man’11), but there is no space to even conceive of resistance to the world itself, its deep structure. You may even be dimly aware that all this is shit; but, the message is, the ego and its system cannot be changed. It is eternal and omnipresent. It is I and I am it; rebels do not question it and even talking hot-dogs unthinkingly submit to it.

You have been reading an excerpt (myth 19) from 33 Myths of the System, a radical guide to the world, rejected by scores of agents and publishers. See also…

The Myth of Meaning

There is no meaning in the system, nor can there be. The system only understands, and only can understand, expansion · · · Meaning is the result of conscious being and of purposeful doing, both of which are impossible within the system and violently suppressed when they appear · · · The perfect system is therefore comprised entirely of unconscious peopl…

The Myth of Education

Education in the system means compulsory schooling in a world of artificial scarcity · · · Schooled activity stunts maturity, punishes experience, corrupts initiative, and cuts the individual off from the world, making self-sufficiency and self-confidence all but impossible · · · The most schooled people on earth are generally the most stupid; the most …

Or defend it from attack, which amounts to the same thing.

Including, via advertising, media ownership and academic sponsorship, the intellectual and emotional environment.

Due to property speculation taking over from productive investment.

Which are increasingly dominated not just by wealthy artists but by layer upon layer of artistic bureaucrat—producers, curators, design managers, ‘creative consultants’ and God knows what else—all of whom stifle actual creative output even further.

As opposed to that imposed and acquired; such as that of those most cultured of people, ancient Romans and modern Nazis. Cultivation of culture from above is a sure sign that its living roots are dead.

Check out contemporary comedy on the BBC, or the (bitchy-yet-politically correct) ‘jokes’ that journalists and wealthy professionals share on social media.

‘One of the contradictions of the bourgeoisie in its period of decline is that while it respects the abstract principle of intellectual and artistic creation, it resists actual creations when they first appear, then eventually exploits them. This is because it needs to maintain a certain degree of criticality and experimental research among a minority, but must take care to channel this activity into narrowly compartmentalized utilitarian disciplines and avert any holistic critique and experimentation. In the domain of culture the bourgeoisie strives to divert the taste for innovation, which is dangerous for it in our era, toward certain confused, degraded and innocuous forms of novelty.’ Guy Debord.

Since the inception of the civilisation which it created and which, in turn, creates it. See Self and Unself.

Was Shakespeare widely praised by his time? Given that you can’t read of his life—i.e. that we have so little material about his life, not even a reliable portrait—it seems unlikely. We also know that he was soon dumped, lying in obscurity for a century while second-rate dramatists had their strutting hour. See The Art of Literature by Arthur Schopenhauer—himself, one of the great ignored voices of history—for a superb, and hilarious, account of how genius is systematically ignored. Presenting artistic truth is, for Schopenhauer, like putting on an astonishing fireworks display to people who are not just blind; but are also fireworks makers.

‘The interior of the temple (of fame) is inhabited by none but the dead who were not there while alive, and a few living most of whom will be thrown out after they die.’ Thus, Jean de Rond D’Alembert, who could also have added that the Guardians of Culture who manage the temple are as blind as Schopenhauer’s fireworks makers. If J.S. Bach turned up at the Proms he’d feel much as Jesus of Nazareth would listening to an Anglican bishop read the Sermon on the Mount in Winchester Cathedral. It’s true that great artists probably felt despair at the larger part of their own audiences, but at least they comprised ordinary living human beings, rather than bloodless stamp-collectors and accountants who appreciate great art in their spare time.

Amazingly, the system actually functions better if the mythic bad-guy is the corporation, the bland company man or the monolithic otherness of the modern world. It is superficially accurate, and therefore superficially reassuring, to see one’s anxieties projected onto the cinema screen—to see the techno-beast overwhelm us, or the plucky young misfit crushed by work—but it all happens in the realm of the known. The structure of human society as we find it, modern ways of thinking and feeling and communicating, these are accepted, unchallenged. Except of course in the finest, and rarest, art.