The Technological System

A Critical Guide to the Machine

…those who use cunning tools become cunning in their dealings, and those who are cunning in their dealings have cunning in their hearts, and those who have cunning in their hearts are restless in spirit, and those who are restless in spirit are not fit vehicles for Tao. It is not that I do not know of these [tools you wish me to use]. I should be ashamed to use them.

Chaung Tzu

The last place the addict looks for the source of his ills is his addiction. If the spotlight of attention falls upon it he squirms, then lashes out. His attention is hopelessly narrow-minded, focused on a range of secondary effects, but never on the cause. Take the technoholic. He worries about the despoliation of the wild, ‘fascist’ mission creep, the criminalisation of gender, outrageous inequality, the state of the youth, rising prices and so on, but he ignores what all these things have in common. It’s like someone who never washes and, rather than deal with this, spends his life fretting about his itchy skin, oily hair and fungal infections, buying medications to deal with these second-order effects and finding ways to ingratiate himself with people who are offended by his smell.

So it is with the wider world. When it comes to our social ills, it’s not just that most people cannot see the wood for the trees, they are terrified of the wood and hypnotised by the trees, transfixed by the isolated ills that face them and afraid of tearing their attention away from isolated bad guys and bogeymen; not to mention from all the conveniences and gimmicks the system provides. This is not an intellectual bias and it has nothing to do with class interests. It is a deep-seated unconscious fear of grasping a truth so immense, so awful, that to do so would annihilate everything they’ve built their lives on.

What then is ‘the woods’? What is the root problem with the world? Is it the ‘New World Order’, a shady group of villains who are pulling strings behind the scenes for their own benefit? Are we speaking of a ‘conspiracy theory’? Is Big Money the problem here? Do we need to expose the secret agendas of multibillionaires? Must we come to an understanding of how corporations, states and — the real power players — investment companies and banks, operate? Clearly we must. Clearly all of this can throw light on our parlous situation.

As can analysis of that great modern bogeyman, ‘capitalism’. Despite the fact that socialism and communism are both integral elements of the system, and ultimately support it, we do live in a world built on capital, on private ownership of the means of production, and we do live in a world in which wage-slavery and debt-slavery, the twin pillars that capitalism is built on, have made a wasteland of the earth. This is why, despite the disastrous limitations and inherently tyrannous nature of socialism and communism, the Marxist tradition has a great deal to teach us, and is a fearsome weapon in our fight with the owners and creditors that control our lives.

But. Neither Globalist Supermen nor the capitalist wing of the system is the cause of our troubles any more than immigrants, my parents, snowflakes, communism, Trump or ‘the devil’ are. Those who believe such isolated, secondary effects are causally ‘behind it all’ are ensuring that, at best, the real problem goes undetected. By ignoring the ground and root of our ills, those who spend their lives focused on attacking capitalism, zeroing in on the oligarchs, billionaires, banks, and the autonomous ‘vampire-like’ activity of capital, only end up reproducing tyranny in another form.

Here we might make special mention of ‘the left’, that group of people who pour their energies into getting a fairer wage for Bangladeshi sempstresses, defending minority interests, promoting what they call ‘democracy’, trying to save the sea-plankton, criticising the American military juggernaut and battling away at greedy, ‘undemocratic’ landowners. These may be noble crusades, but, as a whole, focus on such symptoms draws fire away from the sickness which produces them; which is why leftism (in all its forms) is the most effective means by which the system can protect and perpetuate itself..

Obviously, ‘the right’ aren’t any closer to seeing things clearly either, obsessed as they are with controlling the uncontrollable (the people, the weather, the market), excluding the unexcludable (minorities, foreigners, women), hoovering up every last shekel on the planet and trying to return to a world that is lost forever. The left and the right are perpetually at odds about how to go about organising society, constantly criticising each other — the fraternalist left focusing on the monstrous greed and small-mindedness of the right and the paternalist right on the moral hypocrisy and individuality-annihilating blandness of the left — but neither of them are even slightly interested in the real problem, because they both benefit from its continual existence, which is why, when confronted by a threat to it, they forget their differences and instantly unite to crush their common enemy.

So what is The Real Problem? What is the ‘woods’ that so very few people can look at squarely, that stands both behind and part of all the menacing, monstrous ‘trees’ they heroically confront? What is that which both the right and the left serve, which runs their lives and ours? What is the cause of the horror we see around us — and feel within us — and that, many of us now know for sure, can only get worse? It is the technological system, and it is the human ego which built and maintained it. I’ll restate that. The horror, the nightmare world we live in, which is set to get worse and worse and worse, is the result of the unnatural technological system we have built, and, deeper than that, the ego which built and which continues to maintain and defend it.

By ‘the technological system’ I mean the unnatural industrial-technological world-machine that surrounds us. The ‘hardware’ of this machine is the superstructure of iron and steel, coal and oil, plastic and polycarbon, copper wire and fibreoptics, diode and microprocessor, box-ship and plane, computer and smartphone, road and rail, and so on. It is the mind-made substance of modernity which surrounds us; all the engines, factories, instruments, computers and various tools of the world. The ‘software’ of the machine is all the modern institutions we are familiar with — the prisons, schools, universities, law courts, offices and so on — and the information these organisations ‘run on’ — the ideas, ideologies, theories and beliefs — and capital — required to keep it all going; all the intangible organisations and organisational processes which operate the tools of the world, and all the facts required to build, maintain and justify them.

Thus the technological system is consubstantial with capitalism and socialism. ‘The technological rationale is the rationale of domination itself. It is the coercive nature of society alienated from itself’ as Horkheimer and Adorno put it, meaning that the rational demands of the machine, the rational demands of power, its imperatives of subjugation and control, the techniques of bureaucratic fact-gathering and data-flow which the system demands, all are one and the same (which is why schooling everywhere in the system promotes the professional self-suppressive ‘values’ it does). That we are focusing here on technology as a primal fact of the system should not be taken to mean that technology is fundamentally something other than the states, corporations, religions and professional institutions it merges into.

For many thousands of years, even until quite recently, it was possible to escape from the reach of the technological system, but eventually, over hundreds of generations and after many setbacks and cracks, through which free people were once able to slip, it all came together. This final consolidating process began in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, with a massive lurch forwards in the power of the ‘software’ of the system (including the software of newly-individualised egos, cut loose from old social ties), then, in the industrial revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in its ‘hardware’. Finally, around fifty years ago, all barriers towards a complete world system were lifted and we hurtled towards the state we are in now, standing before the doors of a complete technological dystopia, one so pervasive and invasive it literally inhabits the psyche of those who are part of it, such that it becomes, to machine people, meaningless to speak of freedom. Freedom from what? The prison and the prisoner have become one.

Now, it is critical to understand that although, as I’ve said, there are people who are responsible for all this — the owners of the system, particularly, but also its management class, its academics, doctors, priests, journalists and so on — and although such people should (and will) be held to account for their monstrous violence and cowardice, the technological system itself is, to a significant degree, autonomous. It has its own objective priorities and demands which its human servants must obey or be crushed.

To take a recent example, why is the communications technology of the developed world being upgraded to ‘5G’? Nobody really needs it, nobody really wants it, except perhaps a few technolotrous lunatics. The internet works fine — too well in fact; but we certainly don’t need it to be a hundred times faster. So who does need it? We can certainly say that tech companies do, who depend on continual ‘innovation’ for their power and profits, and we can certainly say that states do, who need hyper-rapid internet systems to more easily monitor and control their citizens. But the most important thing to understand is that ultimately the development of the technological system itself ‘requires’ 5G. As the system becomes more and more complex, more and more invasive and, consequently, more and more destructive, its communication systems require more and more power — which is why it must have 5G. Then as soon as one state or institution adopts this technology, and more ‘perfectly’ controls its environment through it, so everyone must immediately do the same to prevent themselves being overwhelmed.

Technology, the dominance of alienating machines (rather than empowering tools), has worked this way since it first took control of human affairs, many thousands of years ago. Every time a foundational tool or process has developed to the point that it has become too powerful or complex for individual human beings (or local communities) to control, it has forced complete social upheaval in order to accommodate the change. When, for example, two aspects of British society industrialised—mines and cotton factories—a vast number of attendant aspects had to be industrialised; because you can’t have machine power and machine-fabrics without machine-foundries, machine-logistics and machine-education. Every step of every ‘progress’ requires an accompanying development in every other technology — not to mention in the thoughts, feelings and lifestyles of the people who must use or be subjected to the use of these technologies. This leads to all kinds of unforeseen problems which then require more technological fixes.

Such problems today include the immense, swollen power of tech companies and of bureaucrats, the annihilation of the wild, the predominance of domesticated herd-rule (aka ‘democracy’), the death of culture (and of nuance), the ruin of children and the corruption of innocence, the humiliation of the spoken word, the decay of community and conviviality, the abolition of human dignity (particularly through meaningful artistic-artisanal work), vicious and callous abuse of the poor, suffocation of spontaneous instinct and the hollow, purposeless, futility of modern existence.

All of this is, ultimately, a result of the technological system. Right-wing owners make critical decisions, as do left-wing managers; but it is the system itself which commands them. People complain about the withering away of traditional values, about the rise in crime, about their heart-dead children, about their stressful lives, about the blasted immigrants buying up the town, about the poor quality of goods and services and about the maddening frustration of trying to get through to someone who can help them, and then they seize on the next most immediate cause of these things, without realising that the horrendous frustrations of modern life are because they live in a colossal machine which inevitably produces all these results.

Take for example immigration. For the past century the technological system has demanded that huge numbers of people shuttle around the world; and so they do. That so many ordinary people don’t like to have the places they live in overwhelmed with foreigners, or their families fragmented and their traditions diluted, is neither here nor there. The technological system needs it, so everyone must put up with it. This is why, when the system started to need the mass-movement of people, ‘tolerance’, ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusiveness’ became religiously important and why ‘racism’ — which here refers to forms of social complaint — took on the status devil worship did in medieval times.

Or take another example, the utter destruction of childhood innocence and freedom — and therefore sanity. Again, the technological system demands it. It must have children rigidly schooled in its procedures and values, and it must now have them engaging with ‘society’ through the screen. This, combined with parents’ terror of the real world and a social premium on ‘non-violent’ permissiveness — both of which are also consequences of the technological system — combine to create the stupid, sickly, cultureless, sick, sleep-deprived, anxious, anti-social, egomaniacal, hysterical and yet creepily unfeeling laboratory monkeys we once called our children (not to mention a society of child-minded adults who dress, speak and behave like fourteen-year olds).

Perversely, this annihilation of sensitive minds has gone hand-in-glove with a morbid worship of youth and youthfulness. Why? Again, we need look no further than the technological system which, as Jacques Ellul points out, prefers its users to be fungible (if the youth don’t resemble each other more than older people, they certainly fear the exposure of individuality more), full of energy and able to adapt to today’s technological requirements, which are of necessity quite different to those of a few years ago. This is why ‘the face of the youth inspires confidence’, just as a new car does, or a well-ordered spreadsheet.

Plastic is another example of ‘technological necessity’. For the past century the technological system has demanded that we build our entire world from plastic, with catastrophic consequences. Plastic slowly degrades into tiny particles which infiltrate the things we use, our food and water and the air we breathe and have been shown to act as vectors for a wide array of contaminants, including pesticides, persistent organic pollutants, heavy metals, and antibiotics. These particles, which are chronically toxic (neurotoxic, genotoxic, hepatotoxic) and carcinogenic, are then absorbed by and accumulate in biota tissue, organs, and even cells, causing a range of diseases. They also degrade soil fertility. What choice did we have in all this? None.

Or let’s consider social control. Western countries are headed towards a society, in which citizens, rated for how trustworthy or contagious they are, are automatically disciplined and controlled through invasive, automated systems of surveillance and punishment. Even in places like China and the UAE this system is in its infancy. The techno-dystopian horrors to come will be far, far worse than the automated ‘security’ systems already on the horizon, and will all but extinguish the human spirit for good. Why? At this stage only lunatics, morons and cowards believe it is for our health, safety or security. But neither is it happening, ultimately, because Machiavellian demons are consciously designing a world of living death. Once again, there are such monsters at the top of the Pyramid of Evil, and they do have significant control over banks, investment companies and the like, and they will get what’s coming to them, but all this is happening, and must happen, because a high-tech prisonworld is what the technological system itself demands. The supermachine is inherently unstable, unnatural and anti-human, which means the more powerful it becomes, the more rigidly it must control things (and turn people into controllable things) to keep it all together.

Or there’s the mind-crushing borrrrdom of modern life, its total absence of adventure, mystery and surprise. Once again, this is a requirement of the machine, which cannot operate in an environment of unpredictable danger or irrational ineffability. Everything which does not fit, which cannot be rationalised into a discrete thing, which cannot, thereby, be managed, must be levelled out by a machine system. Everyone feels the pain of living in a boring dystopia, all the way up the ladder, but all who work within the system are helpless to do anything about it, because allowing things to go haywire, allowing the kind of free spontaneity which leads to the wild, adventurous uncertainty we all (despite ourselves) crave, or allowing people to work slowly and carefully to create mysterious fractal beauty; all this disrupts the rational ordering of society, sending ripples of fear through the boring monsters who own and manage it. This is why everyone everywhere, with astonishingly few exceptions, looks as if they are stuck in a traffic jam.

Related to this, is the heart-rending loneliness of modern life. Not, note well, the liberation of genuine solitude, in which free individualism reveals itself, but a constraining atomisation in which, although one appears to be ‘free’ to pursue gratification, it is in a personal, virtual space untethered to reality, the result of advanced technological devices, such as cars, televisions, central heating, smart-phones and washing machines which detach men and women from focal, and therefore social, locations, such as the fireplace, the stage, or the river. Technology panders not to the individual character, allowing it to exalt in solitude, but to the needy personality, which grasps at a self-assertive ‘freedom’ that hi-tech devices offer while, at the same time, turning away from the focal places of the world where other people were once found. This is why the more advanced the technology, the more atomised, and therefore bored and lonely, the society.

Or there’s ‘the woman problem’ — that’s what feminism was called when it first appeared in the nineteenth century, when industrialisation forced women to enter the male domain, where they faced a radically different form of subjugation to that they had known. Prior to industrialisation women often had as much power as men; contributing to the wealth of the household and controlling its expenses. When they found themselves in the novel and unpleasant situation of being ordered around in their work, they responded with ‘feminism’. This ‘feminism’ was then used by the system, over the century and a half which followed, to coerce women into an economy which they had and still have absolutely zero meaningful power over. The only ‘power’ they could obtain was that offered to those who crawled their way up the mountain of excrement called ‘career’, a process which corrupted or compromised the femininity it might have liberated. Finally, as the technological system overcame the whole self, not just gender but sex itself was abolished, sexual difference being a barrier to the undifferentiated, bodiless ghosts the virtual system demands. The technological system, in other words, created ‘the woman problem’ and solved it by effacing woman.

Another consequence of living in a machine, perhaps the final and most awful of them all, is the rise of so-called ‘Artificial Intelligence’, which, as everyone is now aware, is rapidly turning life into an inhuman nightmare. Artificial Intelligence is, as the name proclaims, artificial; it is not real. It is, unlike natural, embodied, human intelligence, innately unempathic, innately hyper-rational and innately ruthless. Its decisions cannot even be described as ‘cold’, as there is no possible feeling, or consciousness, which it can betray. If you push the wrong button, or add the wrong file, or are late by one second, you fail, you lose. On top of this, the hyper-complexity of artificial intelligence guarantees constant failure and error and the growth of this complexity—along with its omnipresent invasiveness—ensures that these errors become more and more horrific. But again nobody is to blame; AI is being introduced everywhere because it has to be introduced. The system cannot allow real intelligence to operate; it is too slow, too generous, too disordered, too costly.

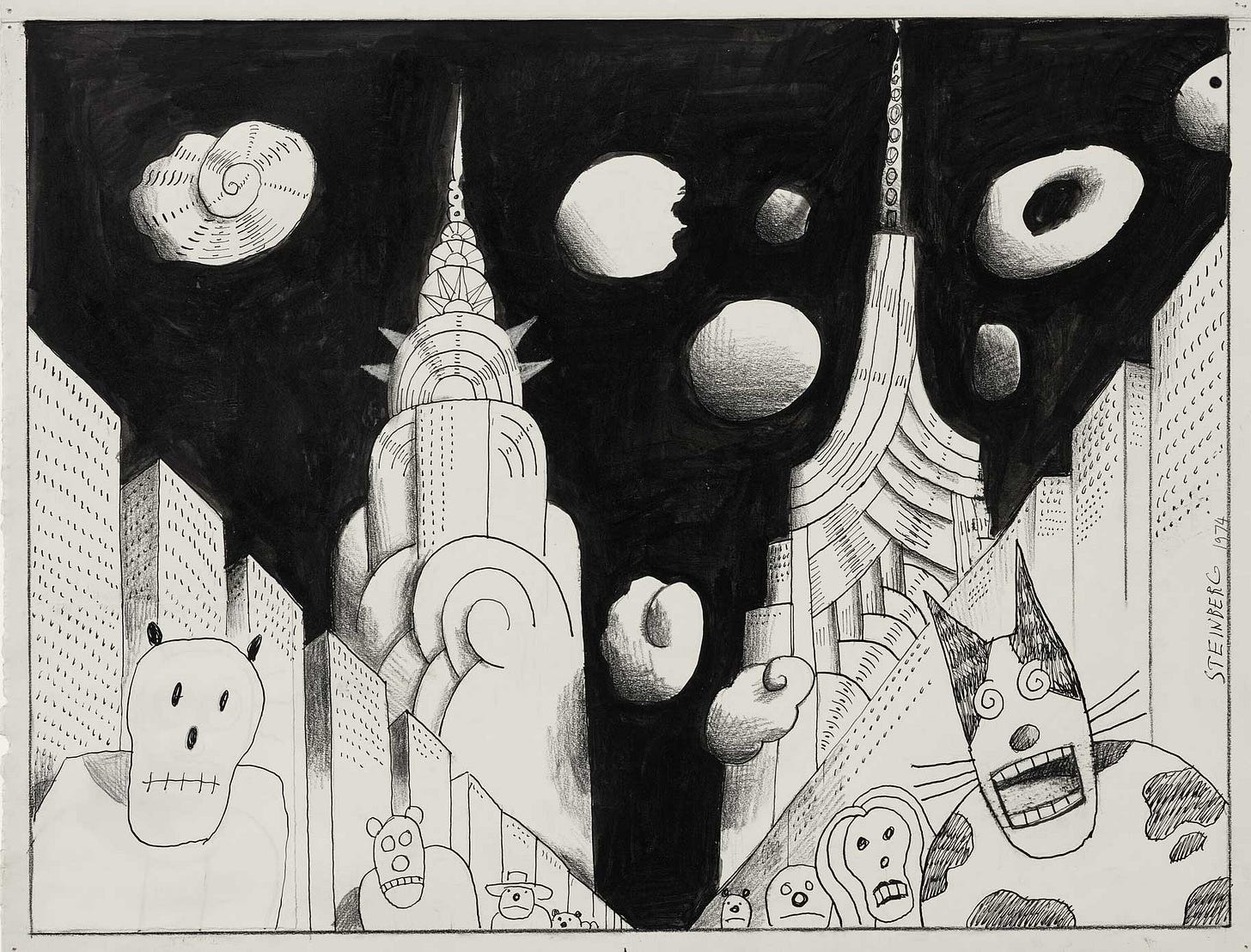

Not that, it is very important to understand, the social wasteland we live in is a result of AI, or even of the internet. Man has been alienated from his own existence since the birth of civilisation, and the creation of a civilised God that took all his creativity, wisdom, consciousness and love and threw it up into the inaccessible heavens. Nevertheless, until the modern machine age, man was not alienated from his own sensory existence on earth, which flowed through time as his life and his labour. The industrial world took this meaningful experience of time out of his hands and replaced it with the things of industrial production which then appeared to him as alien artefacts. He had no more idea of how his gadgets were made — above all the mega-gadget of the modern city — than he had of where the ingredients of his breakfast came from. He was now an exile from his own existence, alienated.

Alienation compels man to substitute meaningful living with objects. Man no longer exists consciously in time, and so he throws his consciousness out into the things — including the ideas and symbols—that appear to him in space. These fetishised things include his possessions, his status, the idea of his family, his money-value, his beliefs and his identity, including all his problems and ambitions, all of which provide him with the semblance, or image, of meaning, without the pain and difficulty of having to live differently. This is why it is usually fruitless to try to solve the problems that people come to you with, because the problem is not the problem.

The problem is not this or that ideology, religion, ‘mental illness’ or way of thinking; it is the way man must live in order to fit in to the technological system, a system which compels man — particularly the professional man—to suppress strong feelings and individuality, in himself and in his perception of others, because they interrupt organisational efficiency. Flattened affect (‘yeah, not too bad, yourself?’), absence of strong likes or dislikes (you never know if someone you upset might be useful to you later), a blasé attitude to experience (shrug), blunted discrimination (a complete inability to tell the difference between useless genius and marketable talent), a cold, reserved, yet restless intellectual gaze (the flat, inexpressive eye of modern people) and a constant ‘pricing up’ of people and things (knowing the cost of everything and the value of nothing), are what modern life demands, which is why there are so few individuals in modern life with any real passion, or any ability to discriminate, or who care very much about quality, which, further, is why everything and everyone who lives in and as the technological system is more or less the same, lifeless, fungible thing; necessarily packaged in glaringly novel forms, to compensate for inner nothingness and to meet the needs of a system which forces man to compete for custom by occupying ever finer niches — adopting ever more special appearances — in the expanding machine.

We cannot leave this carnival of nightmares without touching on the philosophy of the machine, the cultural trend known as ‘postmodernism’, which, consonant with the demands of the technological system—the demands of its software, that is—rejects all limits, barriers and distinctions, justifies or actively promotes the dissolution of cultural boundaries, celebrates the end of sex and of gender, effaces the difference between childhood and adulthood, or between the public sphere and the private domain, justifies the obliteration of tradition, and makes all discernment, between beautiful and ugly, right and wrong, good and evil, life and death, and love and hate, at best meaningless (at worst, fascist). The ideological industry had to manufacture this philosophy because the software of the machine world demands complete permeability of form. Form—what we might call manifest, boundary-limited, meaning—must, in a totalising mechanised system, be ‘free’ to meet the machine’s operative demands of the moment without being constrained by anything; the embodied mystery of femininity, for example, or the place-specific quality of natural culture, or the innocence of childhood, or the demands of craft or a morality empathically rooted in actual experience. The virtual space is bodiless, placeless, knowable, manageable, instantly acquired, without ethical ties or moral responsibilities, without history or memory or any sense of destiny, which is why it demands a philosophy, or cultural idiom, that justifies all this; postmodernism.

The postmodern horrorshow both justifies and perpetuates the complete destruction of sensate culture. We now live in a shredded social wasteland, in which human relations have been replaced by monetised simulations which can be autonomously managed in the same way that a bank account or a character in a game can. Human virtues, such as empathy, sociability, loving kindness and justice have no place in the virtual condition, because they cannot and must not. Intricate natural complexity (or ‘fractality’), sensation which incites reverie, which slows consciousness down, which frees it from emotionally potent stimulation, which is difficult, which requires intelligence and sensitivity to makes sense of — all of this must be banished from experience, from urban and virtual environments. Only those attributes and non-experiences which serve the system are allowed to thrive; technical skill, narcissistic apathy, absolute egoism, restless, painless abstraction and numbed passivity. Result? People are going out of their minds. Depression, anxiety and schizoid insanity are now everywhere, and with them, the dissolution of human individuality.

The machine, itself a product of the highest intellectual energies, sets in motion in those who serve it almost nothing but the lower, non-intellectual energies. It thereby releases a vast quantity of energy in general that would otherwise lie dormant, it is true; but it provides no instigation to enhancement, to improvement, to becoming an artist. It makes men active and uniform—but in the long run this engenders a counter-effect, a despairing boredom of soul, which teaches them to long for idleness in all its varieties

The machine is impersonal, it deprives labour of its dignity its individual qualities and its defects that are characteristic of all labour that is not done by machines—therefore, a portion of humanity. In other times every purchase made from artisans was a distinction conceded to a person, whose signs were all around him: so the usual objects and clothing became symbols of mutual respect and personal affinity, while today it seems that we live only amidst an anonymous and impersonal slavery. The lightening of the burden of labour must not be bought at so high a price.

Human, All Too Human, Friedrich Nietzsche

The hardware of the machine requires a different, but complimentary ideological foundation. This is called ‘scientism’ (or materialism / physicalism), which is the assumption that reality is made up entirely of discrete, isolable bits, called things or facts, which have a rigid causal relationship to each other. This, for the physicalist, is ‘reason’, ‘reality’, ‘truth’ and ‘sanity’, because extreme fidelity to caused facts is both necessary to build the machine and is impossible without it. Non-causal, non-factual experience is, for the physicalist, indistinguishable from the lies and insanity of postmodernism, which scientism appears to be at continual odds with, just as the right appears to be at odds with the left, craftsmen with artists, crew with cast, men with women. Appears to be, but the egoic foundations are identical, and are founded, in our world, on the monolithic, totalising technological system.

All of the above explains why people are going out of their tiny minds. Their lives are meaningless and they, as human beings, are becoming redundant. I don’t mean they are losing their jobs—which would be a reason to celebrate—I mean they are useless, superfluous to requirements, not just unable to do anything with any skill, but unable to contribute in any meaningful way to society and punished for even trying. This inevitably leads to ghastly feelings of futility and depression, which people are encouraged to assign to all kinds of reasons (chiefly ‘mental illness’) but the real one; the technological system, which must expel as many humans as possible from its operations or, if that’s not possible, expel genuinely human qualities—such as creativity, generosity, fellow-feeling and so on—from the people who remain within it. Such qualities cannot be controlled and, more often than not, disrupt the smooth operation of the machine, so they cannot be allowed, which is why only machine-people rise to the top in the technological system; unempathic, cowardly, hyper-analytical humanoids.

Owners and managers might occasionally have some need for beauty in their lives, they might value spontaneity and generosity, they might love wild nature, they might have all kinds of human qualities. It’s unlikely that there will be many such qualities or that they will be of much profundity — for it’s the ‘least among us’ who lead — but there might be something good somewhere in there. The system, however, has no use for the good. None. Radical beauty, innocence and honesty, integrity and decency, genuine originality, thoughtless generosity, ungovernable wildness, unconditional love are all threats to the smooth running of the machine, which is why all these things are vanishing from our lives.

All the problems I have mentioned are a direct or indirect consequence of living within and being forced to serve the technological system. This includes the financial and legal systems and the demands of capital, exposed by Marx, to innovate workers to death (into machine-like productive processes), but it is also independent of them and, more importantly, ignored in the Marxist tradition which, like every other political system, accepts technology as a neutral substrate on which the organism of society grows. Radicals might want to end biofascism or the destruction of the wild or the abuse of women or private property or wage slavery, and that’s all fine, but if technology is allowed to maintain its hold over men and women, nothing will or can really change and all ‘solutions’ are merely palliatives.

Consider the following story. An insecure man — let’s call him Tom—greedy for wealth and power, takes a stressful job in the middle of a city. Tom has no access to wild nature, no community around him to speak of — just work colleagues and a partner — and he is working flat-out at an essentially pointless task in the city, with no free time to discover and pursue interests which are meaningful. He is surrounded by thousands of objects that he has no meaningful connection to, that, for all he knows, were beamed down from an alien planet, he is completely dependent on an army of specialist fixers to feed, clothe, transport, entertain and protect him, and on an immeasurably complex technological system to communicate with his society; which, actually, is no longer a society at all, but a series of algorithms masquerading as a society. After ‘living’ like this for a decade or so, Tom gets sick and unhappy and starts to deal with his sickness and his mental health problems. He gets stomach pains, so he takes painkillers or alters his diet; he feels stressed, so he meditates or goes on holiday; he is bored, so he watches a movie or gets high; he is lonely so he uses social media or sees a prostitute; he is angry, so he criticises the government or goes on a march… and so on. All the problems are seen in isolation. At no point does he identify the technological system as the problem. Why? Because the actor and the play are one.

I’ve chosen here rather a crude example, a fellow that some readers will no doubt dismiss as just one of ‘them’, but everyone within the technological system is attached to it in much the same manner, from the most aggressively independent right-wing businessman to the most groovy, eco-radical leftist author, from the wealthiest billionaire, at the pinnacle of the techno-pyramid, through all the intellectuals, thinkers and professionals, down to the ordinary workers and the poor. All are plugged in, to their roots, which is why so many people, from all classes of society, are disturbed by the prospect of genuine independence from the machine. The socialist who wants ‘a fairer society’ or ‘an eco-friendly city’ or a ‘civilised world’ — we might not like such people, but we understand them. The madman who does not want a ‘society’, a ‘city’, a ‘civilisation’; this is the devil’s work.

All man’s egoic insecurities and cravings, his docile conformity and numbed passivity, his restless need for stimulation are plugged in, at every point, to the technological system, manifesting as his whole life. He cannot see the big picture, because to see it means that everything must change. Not just this or that activity or habit, but everything, his whole being and, consequently, his whole way of life. So he goes on identifying this or that problem and pursuing this or that isolated, short-term solution, until he dies.

This is how evil grows, by offering the lesser of two evils

until all the good has gone.

Those who own and manage the system well know that people are like this, and so they make sure that problems are presented without context and that solutions amount to nothing more than relieving immediate fears and stresses, all but ensuring that the passive mass are all together caught up in the panic of the day and all too willing to sacrifice more of their freedom and dignity for a short term fix; a little less fear, a little less insecurity. This is how evil grows, by offering the lesser of two evils until all the good has gone.

None of this means that men and women weren’t or aren’t capable of being greedy, selfish or stupid before or outside the technological system, nor that those men and women who are independent of the system to any significant degree are necessarily paragons of virtue. What it means is that, naturally, selfishness has its limits; it is restrained by the people around us and by the limitations of the society around us, which prevent selfishness from ruining our lives or those of our fellows. When the unnatural system reaches the size, extent, invasiveness and power of the modern world, there is no limit to how much the ego can feed from or be fed by it.

Opportunities for addiction, escapism, irresponsibility and so on are virtually limitless in the fully developed system. Not only that, but the power of the system to pander to the ego, to flatter its vanities, excuse its fears and feed its baser impulses makes it almost impossible for men and women to resist its insidious creep into their lives. The system — by offering constant micro-hits of social-media fame, by rewarding failure, by lulling men and women to sleep with central heating, smartphones, video games, antidepressants, Pringles and endless porn, by rewarding those who comply, who bend over, who are obedient and subservient, by making it impossible to ever fully confront pain, dirt, loss or hard work, by rebranding self-love, conceit, cowardice and spite as mental illnesses or even as laudable values and by making love completely unnecessary — all this, along with the various illusory myths that the system furnishes its addicts with (chiefly that there was a lower quality of life in the pre-civilised, or even pre-modern, age), lets the selfish ego entirely off the hook which, as spoilt children everywhere testify, turns us all into monstrous egomaniacs, pitiful cowards and craven addicts.

Completely rejecting the system might seem like an entertaining idea, but when voicing your doubts — much less doing something about them — threatens your bank balance or your job, suddenly ‘prudence’ and ‘caution’ are required. This is why almost nobody can see the wood for the trees, because to do so, in the advanced system, means to reject a parasitical false self which has so overwhelmed consciousness that nothing else — no other quality — can be experienced. An inability to see the woods, to see the true cause of the world’s ills is not a question of intelligence and certainly not of taste or education — usually the most educated are the most morally blind and the most tasteless and uneducated the most perceptive, at least when it comes to seeing the true nature of the system. Men and women do not turn away from the truth of the world because they cannot intellectually understand it, or through error or blindness. They turn away because to see the nature of the technological system is, for the ego, to look straight into its own death; because it must die to be free.

Fortunately the system is dying, as all things do. It too is reaching its limits (imposed on it by its energy requirements, which exponentially outstrip cheap supply). This, like the much-vaunted ‘end of work’ that is also coming down the tubes, would be a cause for celebration were it not for the fact that these final stages are going to see the nightmarish perfection of the technological system. Its hold over our lives is going to be complete. We will be locked into a dystopian horror that our greatest writers could scarcely imagine.

But not for long.

Meanwhile, what can we do? If you understand The Problem clearly enough, the response to it is obvious. What happens when you clearly see, for the first time perhaps, a bad habit that you were not aware you had; that you don’t pay attention, perhaps, when someone is speaking to you? Do you need a solution to this problem? Do you need to be told what to do? Or is it obvious?

Well, we are not paying attention. If we were, we would live differently. We would liberate ourselves, as best we can and, in so doing, we would feel good. It feels good to have a noble purpose and to work towards it, even if you never objectively succeed. It feels good to strive to overcome your machine-made fears and desires, even if you are never completely free. It feels good to be independent, even if you must compromise somewhere along the way.

This doesn’t mean you must immediately give up using all industrial technology. That is also impossible — as the fact I have written this on a laptop demonstrates — as well as absurdly simplistic. The technological system has, as we have seen, distorted our relationship with each other; it has taken simple tools from our hands and made us forget how to use them; it has placed us under the thumb of technocrats, professionals, teachers, doctors and professional ‘security’ forces; it has corroded our intelligence, drained us of energy, sickened us, confused us; it has even deprived us of our language, inserting itself between our understanding of our lives and the means by which we once creatively expressed that understanding. Freedom from the machine world isn’t just a question of chucking the smartphone, nor even of identifying and confronting our alienated cravings and justifications. It’s not enough to fight the machine on one front, the most obvious, the most direct — although that too, obviously — but, as it has insinuated itself into every aspect of our lives, even our thoughts and feelings, so every aspect of our lives is an arena of engagement, a nemesis to overcome, a prison to escape from — and the prison is ‘I’.

I don’t mean to suggest that self-overcoming and personal revolution are the only way out of the technological system — obviously not. That would amount to chronic self-absorption. Even the revolutionary acts we are called upon to make in the world, once we are determined to free ourselves of its hold over lives, are not enough (I am referring to our battles in the workplace, in the neighbourhood and with the various institutions we must deal with). Something much more thorough is required to bring the system down.

Here we must recognise something else that is not always obvious about the technological problem, aside from its breadth and depth; something that must also be considered if we are to confront the machine-world intelligently, and that is the fact that it cannot be reformed. Ever. Just as every major development in the system immediately generated concomitant developments everywhere else, which seamlessly integrated themselves with each other, so the autonomous nature and almost inconceivable power of the system — not to mention the sludgelike passivity and learned helplessness of the domesticated mass — remains completely untouched by piecemeal adjustments, which almost instantly hit institutional limits by virtue of the fact that everything else in the system is threatened by them.

We’ve looked at one intimate example of this in the life of poor Tom, who is unable to deal with any of his problems because they are all rooted in the same sterile soil. Just consider, by way of just another, less personal, example, what it would mean to meaningfully reform schooling, so that children could learn their culture in the manner they have learnt it for hundreds of thousands of years, by directly participating in it. In order for this to work, everything would have to change — all of society would have to become educational; it would have to become a place that children can learn from, rather than a place they can do nothing but passively observe. And when I say ‘educational’ I mean meaningfully educational; allowing children to discover who they are, rather than forcing them to do what the system requires. What’s more, all the system-made distractions and addictions which would instantly absorb the attention of children allowed to live freely would have to be removed from their lives. All of this would mean the total disintegration of every aspect of the system.

Similar considerations prevent us from ever taking any of our technologies a step back. Consider what it would mean to return to horse-drawn carriages, or to coal-burning heating systems, or to paper- and tape-based information and filing systems. Again, everything would have to change. Only forward makes sense to the technological system, only more, only bigger. ‘Less’, ‘backwards’ and ‘smaller’ are as inconceivable to machines — and to mechanised minds — as better. So it must go forward, and those who dream of a future utopia must assume that it will be, with various permacultural frills and eco-harmonious designs, more developed.

All of this applies to meaningfully addressing — as in actually solving — any one of the following problems; nuclear weapons, the emptying of the oceans and the erosion of top-soil, overpopulation, genetic engineering, the proliferation of microplastics and other pollutants, widespread madness (addiction, anxiety, depression, etc.), the death of culture, the death of gender, generalised incompetence, outrageous inequality, corruption, the iniquitous exploitation of the poor or any of the other problems I’ve mentioned so far. Even if any one of these things could be effectively dealt with within, say, a hundred years — which is very unlikely — dealing with any one of them throws the whole system into disarray, which is why defenders of the system simply will not allow any aspect of the system to meaningfully change — even if it could — which is why, further, as any reader with the slightest intellectual honesty will recognise, there has been no real progress dealing with any of the serious problems humanity faces. None.

You can believe that a few new laws will fix things, or that a new green technology will be invented which will magically clear everything up, or that a successful anti-lockdown movement will liberate us, or that the ‘right leadership’ will rescue us all, but only by not paying attention to how tightly integrated the system is, how widespread the wasteland world actually is, or how profoundly invasive it is, the result of a process which, as mentioned, has taken thousands of years to reach its current global form. Such development cannot be turned around in a few years or even decades. If genuine reform were possible it would take centuries to change society from within, far longer than we have before nature and human nature are obliterated.

The best that can be (vainly) hoped for is that one group of technocrats are replaced by another, trendier group. Such a hope is rarely articulated by radical (leftist, socialist, Marxist or nominally ‘anarchist’) authors, they are rarely aware of it, but this is the inevitable outcome of reforming society without meaningfully addressing the technological system. You can have the landscape scattered with permacultural cloud farms and propertyless vegan love-ins, but if no meaningful movement has been made towards addressing the global machine upon which society is built, a powerful technocratic, bureaucratic class of intellectuals will have to exist to maintain it. This class will then be what powerful professionals always are — bland, bodiless brains on legs — and do what powerful professionals always do — dominate society in the name of caring for it.

This is why the perennial objection to these kind of critiques — that ‘technology is neutral’, that it ‘depends how it is used’ — is so short-sighted. Technophiles assume that the internet is the same kind of thing as a stone axe, when vastly complex machines are not just different in degree but completely different in kind to simple tools. It may be the case that a nuclear weapon is ‘neutral’ in the already absurdly limited sense that it can be exploded or not, but, like all the high-tech devices we now rely on, they are part of a system which demands a certain kind of society; namely, the one we have, in which education, politics, law, transport and health are, and can only be, technical concerns.

What’s more, who is to decide how all this technology is used? It’s ridiculous enough to make the claim that we have ‘a choice’ about how we can use bucket-wheel excavators, it’s even more stupid to assert that the technological system which demands the use of such machines is ‘neutral’, but even given these fantastic assumptions, there is nothing in the training of scientists and engineers to enable them to decide how hyper-complex machines should be used, nor can there be; as not only can morality never be found in technical (‘scientific’) education, but is a threat which is and must be eradicated by that education. So what if technology is ‘neutral’ when those with power over it are guaranteed never to be able to use it wisely?

If you have ever discussed these matters with people you will have noted how similar counter-arguments are to those of religious adherents, with the same kind of redemptive beliefs; for indeed we are talking about a religion. Man’s being is so fused with technology, his dignity and strength so dependent upon it — witness the manner in which men compensate for their impotence with big cars and loud music — his pleasures inconceivable without it — he cannot make music, paint, dance, talk, do anything without technology — that any criticism of it evokes irritation, emotion, anxiety, outrage, fury; just as criticism of his religion would, or his nation, or his mental illness or his over-active penis, or whatever other surrogate thing (and it must be a literal thing) he’s poured his lonely, alienated, lifeless being into. It’s not just that cars are fetishised, phones fiddled with, bombs given names and perfectly ordered spreadsheets sighed over, it’s that man himself is a machine, which is why he charges technology with existential power, even erotic power, and why he refuses to take into account the vast whole in which his fetishised gadgets have their place. If he does, if he ‘opposes the machine’ or is ‘anti-tech’, he is always very careful not to let that little part of it that he is spiritually attached to — professionalism, perhaps, or institutional Christianity — to be critically scrutinised.

The technological system has its high priests and fanatical crusadors, and it has its casual believers and lapsed lay folk, but regardless of how conscious individuals are of their technophilia, all are enfolded into the system which produces it. We live to the rhythm of the machine, we encase ourself in its shields, we filter our senses through it and, if we own or manage it, we gain our livelihood from it. We are already cyborgs, our intelligence is already artificial, our reality already virtual. This is why, although a typical modern may well never have uttered a word in its defence, he will react to the idea that we are imprisoned by the technological system, that it is unreformable, that it is not ‘neutral’, that it has its own priorities, that it runs the world and that it ruins man and woman, in the same way as all believers react to the reality of the illusion they live by. He may agree, up to a point, or he may passionately disagree, but he will not change the way he lives.

An earlier version of essay appears in Ad Radicem, a collection of radical reflections on the system and the self.