This is a four-part essay. Part one, here, comprises a look at Orwell’s Newspeak and an enquiry into The Petrification of Metaphor. The other three parts are for paying subscribers. Part two, The Spread of Plastickese is here. Part three, The Humiliation of Speech is here. Part Four, Modern speech is here.

Introduction: Orwell’s Newspeak

Speech is becoming sterile, hollowed out and incapable of expressing meaning. The domain of language was once as rich and extensive as that of its mother, nature, with hundreds of thousands of languages and dialects, each reflecting the depth and variety of existence with an elegance and subtlety which is unimaginable today. Our language is a wasteland. And not just English. Speech everywhere is an empty echo of what it once was. Like varieties of apple and corn, like species of cow and butterfly, like styles of dress and architecture, like faces and character and experience itself, language has been humiliated, corrupted, bleached of flavour and of colour, and reduced to an assortment of manageable things. It is not language at all, but code. Neospeak.

For George Orwell, the means by which dystopian ‘Newspeak’ replaced ‘Oldspeak’ was a relatively crude and straightforward operation; a central power, the state, seeks to control thought by controlling language, which it does by radically simplifying vocabulary and grammar, so that speech can no longer express dissent. Practical, quantitative, utilitarian language, for example, is retained in Newspeak (‘scientific and technical terms resembled [those] we use today’1) because such communication, confined within the realm of the known and the knowable, cannot be radically heretical. Technical language cannot express the qualitative nuance of our inner experience, or that of our social lives.

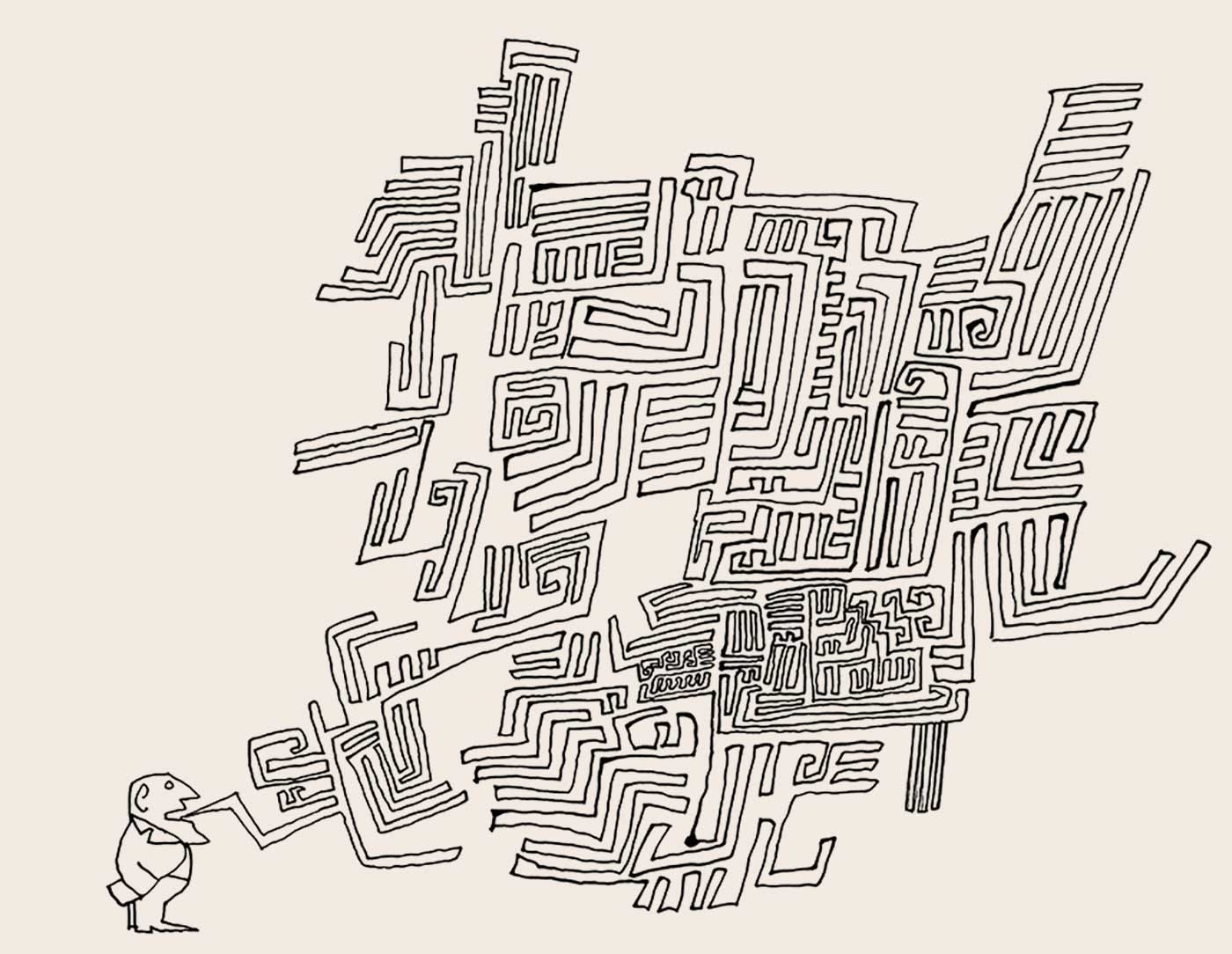

Making speech a technical, quantitative concern automatically deprives it of a vast number of utterances which can express human sense and meaning, particularly those which refer to a personal or social experience that differs from that officially approved; ‘a few blanket words covered them, and in covering them, abolished them.’ The Newspeaker is to think in rudimentary, generalised images which call up strong monovalent emotional associations, while, at the same time, only vaguely referring to the ‘real’ world, a world which is now nothing more than the manifestation of the will of the party, and so innately hostile to a personal, individual apprehension of fact or reality. On top of this, non-literal forms of expression, are also, at least to some degree, curtailed in Newspeak. One is to forced to speak in a ‘gabbling style… at once staccato and monotonous’ which precludes tone, and therefore ironic implication.2 Orwell does not dwell on this, although, as we shall see, it is in its hermetic nature, segregated from gesture and implication and the music of speech, that the dystopian language we actually speak — Neospeak — is at its most nightmarishly dystopian.

Orwell’s analysis of the nature of Newspeak was influenced and restricted by his rational socialism and, consequently, by an excessive focus on the formal, authoritarian state as the primal source of the dystopian information-exchange we call ‘language’. He neglected the wider, subtler, and largely unconscious, system of which the state forms merely an executive part, and this neglect limited his otherwise perceptive analysis of the death of language. Orwell points out that Newspeak is possible only ‘so far as thought is dependent on words’, and of course he’s correct, thought is not dependent on language; but he does not explore the implications of this. Orwell’s Newspeak is founded instead on the idea that subjective experience follows language, and so, if the state cuts down language, the radical subject can be cut down with it. But while thoughts, not to mention feelings, actions and perceptions, certainly are shaped by words, and human beings can be manipulated by language, along with the reality we perceive, ultimately language follows experience, not the other way around. The appalling state that speech is in today is, as we shall see, only partly and secondarily due to Orwellian control of language by institutions. The state endeavours to criminalise and thereby eradicate certain ideas, the cultural elite feel they must fiddle with our pronouns, and advertisers are very keen for us to associate certain words with certain products; but all of this has a relatively trivial effect on our inner life. Even the influence of the languages we speak on the way we perceive the world, which, as anyone who has ever lived with someone from a different culture knows, is certainly of some significance, is trivial in comparison with the effect that experience has on language, which is how we can live together in the first place, much less speak to each other and be understood.

It is quite possible to have radical thoughts and feelings even if we do not have the words to express them; just as it is possible to know ‘what I mean’ without being able to say what I mean. The problem is not that we are forced to speak Newspeak, but that we live in a manner from which Neospeak automatically emerges, a way of life which makes speech meaningless. Just as the sterility of the soil is reflected in the sickness of the trees which grow in it, and in the bitterness of the fruit they produce, so the radical impoverishment of the lives we live is automatically reflected in the radical impoverishment of our speech. The words and expressions we use every day to converse with our fellows has been reduced to match an increasingly stunted and scoured experience, which has no more need of words and expressions which refer to the complexity and subtlety of the natural world or of a natural social life or of the subtleties of conscious experience than an instruction manual for a washing machine needs poetry or a porn movie requires a plot.

Language which describes colour, smell, taste and touch has blanched and shrivelled to fit an external world that demands such speech becomes colourless, tasteless and remote from physical contact.3 Similarly, shades of meaning that mark out nuances in character, feeling, appearance and so on are invisible to modern people and do not need to be reflected in their speech, which withers accordingly. We do not need to develop relationships with our fellows, and to unite with them in a speech that honours the sensitivity and uniqueness of the other, and so the speech, tone and timbre we need to do so just dries up and crumbles to dust, like a flower pulled from the earth. There is no need to impose an unnatural, coercive, degraded language upon this husk, from above, it happens by itself when man separates himself from the living earth, imprisons himself in an unnatural, coercive, degraded world; one which Orwell, for all his inspiring integrity and clarity, could not clearly see.

Orwell described the four basic features of our contemporary unlanguage, but because he neglected the full reason why our language is degraded — the autonomous growth of the egoic system — he missed certain subtle, but critically important features of that degradation. He understood the corruption of reason that Newspeak engenders, for example, but missed the means by which the image has brought this about. He was aware of the utilitarian brutality of Newspeak, but only sketched the connection of this to modernity’s hostility to metaphor. He described the nuance-killing modularity of Newspeak, but was unable to draw parallels between this and the septic spread of anti-culture. He was alive to the erasure of quality in modern language, but was unable to see how this emerges from the slow suffocating death of consciousness, and its unity with the context.

Orwell understood modernist Newspeak, but we now that we actually find ourselves in a degraded dystopian postmodern world, one of neotruth, neomeaning and people, we can more clearly see the features of Neospeak, the empty shadow of language.

The Petrification of Metaphor

The power of speech to express actually existing qualities has been under continual attack for centuries, principally through the literalisation, or petrification, of metaphor. First of all a fresh metaphor appears, a way of expressing a new quality by bringing together two incompatible ideas which share that quality. New words, jokes, puns, idioms — all kinds of shared thought-forms appear this way, from faddish slang, which might last a few years, to idioms and expressions which embed themselves in our everyday language, to high poetry, which spreads across the world, to metaphysical paradigms which extend their reach down through the centuries. A few hundred years ago, for example, a few philosophers began comparing the universe to a machine comprising parts, or ‘bodies’, motivated by various causal agents, such as ‘mind’ or ‘will’ or ‘force’, which enabled us to understand and interact with the universe in a new — useful — way. Initially, this machine metaphor was, like all other metaphors, used knowingly, as a metaphor, but over time the metaphorical element was forgotten or dropped. Just as we no longer think about ‘honey’ or the ‘moon’ when we go on ‘honeymoon’ — the word now simply and literally means a holiday after marriage — so we came to unthinkingly, unconsciously believe that the universe really is, literally, a machine (when it is not), or that causality really, literally, exists in the world, as a discoverable fact (when it does not), or that the objects of the world really are, literally, separate from the subject which experiences them (when they are not).4

Before we killed scientific metaphors, we killed the gods. In order to speak to a society in which form and quality were separated, the gods came to be seen as literally real and existing things, until these things became more important to us than the characters and qualities they embodied and we were left with an empty mythology of dead ideas, a hollowed out, iconographic language of ossified metaphors, which science was able to take, and make mere use of. The word ‘enthusiasm’ for example, which once meant, metaphorically, to be immersed in the mystery of God (En-Theo-Ism), came to inhabit a halfway state, one of religious ecstasy, before the original divine referent was completely lost and the word came to merely, literally mean ‘intense and eager interest’. Likewise, the god Helios became mere fire, Kratos became mere force,5 and then fire and force took on a metaphorical existence of their own which, in turn, sank into the petrifying bog of the self-serving system and became literal things; useful concepts, but unable to describe non-literal reality and, far worse, concealing it from us.

The fluid mask of metaphor thus fuses to the face of meaning, and then becomes it. We are victims of our own creations, victims of metaphor.6 Those still free of the dead weight of literalism are those whose speech delights us with its creativity, who possess an ability to express the quality of the moment by drawing together disparate experience. Not just novelists and great comedians, but ordinary people, particularly those without years of schooling on their shoulders, whose speech is — or until recently was — rich with living metaphor (not to mention living music). They are still directly in touch with experience, which they can draw from to form the slang, idioms and expressions we all use; the unacknowledged legislators of our spoken world. If, somehow, they are able to avoid the stultifying influence of the official cultural world, plumb the rivers of tradition and master language, they become the people we honour as poets, storytellers and philosophers.

Great writers and speakers, those rare folk who are both bright with consciousness and brilliant with the power to express it, are both sensitive enough to detect actually existing quality and intelligent, not to mention disciplined, enough to metaphorically express it. This means they are a primal threat to the guardians of dead metaphor, to the cultural elite above, which builds its power upon the petrified myths of its ancestors, and to the mass man below who, prevented by the system from discovering meaning for himself, builds both self and society upon the literal ideas which are handed down to him. Both groups, the dominator and the dominated, then form an uneasy alliance, constantly at odds over power within society, but instantly united when threatened by a metaphorical incursion from outside it. Both slave and master are intolerant of non-literal language, detest alternative paradigms and viscerally reject new myths and stories, those which apply to reality as it is.

Until recently in the West, the dead metaphor that society was constructed upon was that of a race of sinful, slothful outcasts created, and tormented, by the domineering God of the Torah, the Bible and the Quran. This was superseded by the metaphor of the machine-universe, and the machine-mind, of Hobbes, Bacon, Descartes and Newton, the founders of the dominant ideology of the modern world, scientism. Scientism’s monomaniacal hatred of living metaphor, no different to that of the religions it replaced, makes meaningfulness exclusively a literal, technical concern, one that requires years and years of specialised training to comprehend. This training doesn’t just alienate those who do not have the brainpower, or the class privilege, to master it, but also, ironically enough, those who do, those who spend their lives becoming specialists; for their knowledge can only be gained by splitting the whole of life into slit-thin avenues of expertise which one must spend decades journeying down, only to find that, as soon as one steps a single millimetre outside of one’s specialised knowledge, one is rendered speechless by an inability to apply what one is sure of to what is now before one’s eyes. Witness the specialised scientist when confronted with something which requires a new feeling, a new quality of consciousness, a new form of empathy. He goes to pieces.

The degradation of metaphorical language is a consequence then of the metaphor-resistant ghosts of meaning which haunt our institutions; but only partly, and only secondarily. In truth, the source of our metaphorical poverty, and the drying up of the non-literal waters of speech, is the fact we inhabit a blighted rock, a blasted ruin in which nothing real lives or grows, and no meaningful activity takes place. There is no experience to draw upon to make metaphors. Take, as one simple example, ‘to be out on a limb.’ This expression, one of a countless number we use every day, comes from gathering fruit from trees — from actually being out on a limb, recklessly scrabbling for ungathered cherries — an experience which was carried across (the original meaning of ‘metaphor’) to express similar, but non-literal, experiences of precarious over-reach. But who climbs trees today? Or gathers fruit? Or chops wood? Or does anything practical in the natural world? Who, further, pursues genuinely useful, non-alienating craft activity, the mastery of real tools in the world, the creation of real things, with one’s own hands? Who even uses their hands? Or their bodies? Who seduces or is seduced? Who fights the elements to survive? Who explores new worlds, new feelings? Who does anything human? We do not live in the real world,7 so where are we to draw our metaphors from? Answer; the virtual world. If you want to see or hear what that leads to, listen to the slang of young people, or to the sterile uniquack8 of technicians, or to the self-indulgent, empty metaphors of prize-winning authors, or, if you dare, to the modish fiddle-faddle of journalists, influencers and the like. It is the machine speaking, discharging unreal ideas like a forestry mulcher spews out woodchips, as stripped of metaphor as the earth is stripped of moss and weeds and flowers.

The unreality of their experience, sheltered from the real world, explains why the comfortable upper classes are so stupendously boring, why fame destroys creativity and why great men’s sons, at least insofar as their greatness is a question of genuine creativity, seldom do well. Money, success, attention, power and painless ease all insulate consciousness from the functional world of the senses, from qualitatively new experience and from the subtle realities of social life — actual social life, that is, in which man must, without the crutch of money, depend on his fellows. When the working class rises to a position of propertied privilege the wealth of their culture melts through their fat fingers, when the struggling genius receives the applause of the masses his songs lose their savour, when the son of the great man attempts to follow in the old man’s footsteps, he turns to draw water from a well that is empty.

Assertion of any kind of distinction in a world of indiscriminate cultural or psychological mush becomes indistinguishable from the ravings of a Nazi.

The lack of reality informing the ideas of the coddled and deafened explains their pathological abhorrence of speech with non-literal content. This is particularly evident in highly developed professional Neospeak, the dialect once called ‘politically correct’ when it was confined to university campuses, but, now that it has metastasised into wider society9 is called ‘woke’. The reason why woke speakers of Neospeak are deranged by implication and metaphor; the reason why they need ‘trigger warnings’ and ‘safe spaces’ to protect them from ‘offensive’ language; the reason why it becomes officially impossible to say one thing, such as ‘no’, and mean something else, such as ‘yes’; the reason why no distance must be permitted between how one speaks and who one is; the reason, in short, that implicit meaning must, in highly developed Wokespeak, be conflated with explicit communication, is that there is no implicit meaning left in the lives of those who speak it. They have no quality to draw from by which to interpret speech, so they have to parse, and police, its formal expression. This is why Wokespeakers are, despite spurts of flashy exuberance, so extraordinarily uncreative and humourless and why, now that culture is in their hands, our social lives have become drained of the prerequisite for culture, playfulness.

Absence of reality in official discourse also explains why not just those who use language to refer to actually existing qualities (such as beauty, honesty or excellence), but those who use it to refer to objectively existing facts, are excluded from or punished by modern institutions. Ultimately language, for the institutionalised mind, serves one function only, to manage moral consensus. Thus, even literalism is abandoned if one appears to be using words in a manner which refer to anything other than ‘how things are done around here’. Overtly, vague ‘values’ of ‘inclusion’, ‘diversity’, ‘transparency’ and so forth are celebrated, while covertly they are employed to identify and expel anyone who refers these words to any actually existing thing (e.g. ‘a problem’) or quality (e.g. ‘solving it well’). This helps explain why wokeism inevitably leads to the constant bungling of politically-correct institutions and the creation of a mutinous, beleaguered, dissident minority who are still focused on doing things well.10

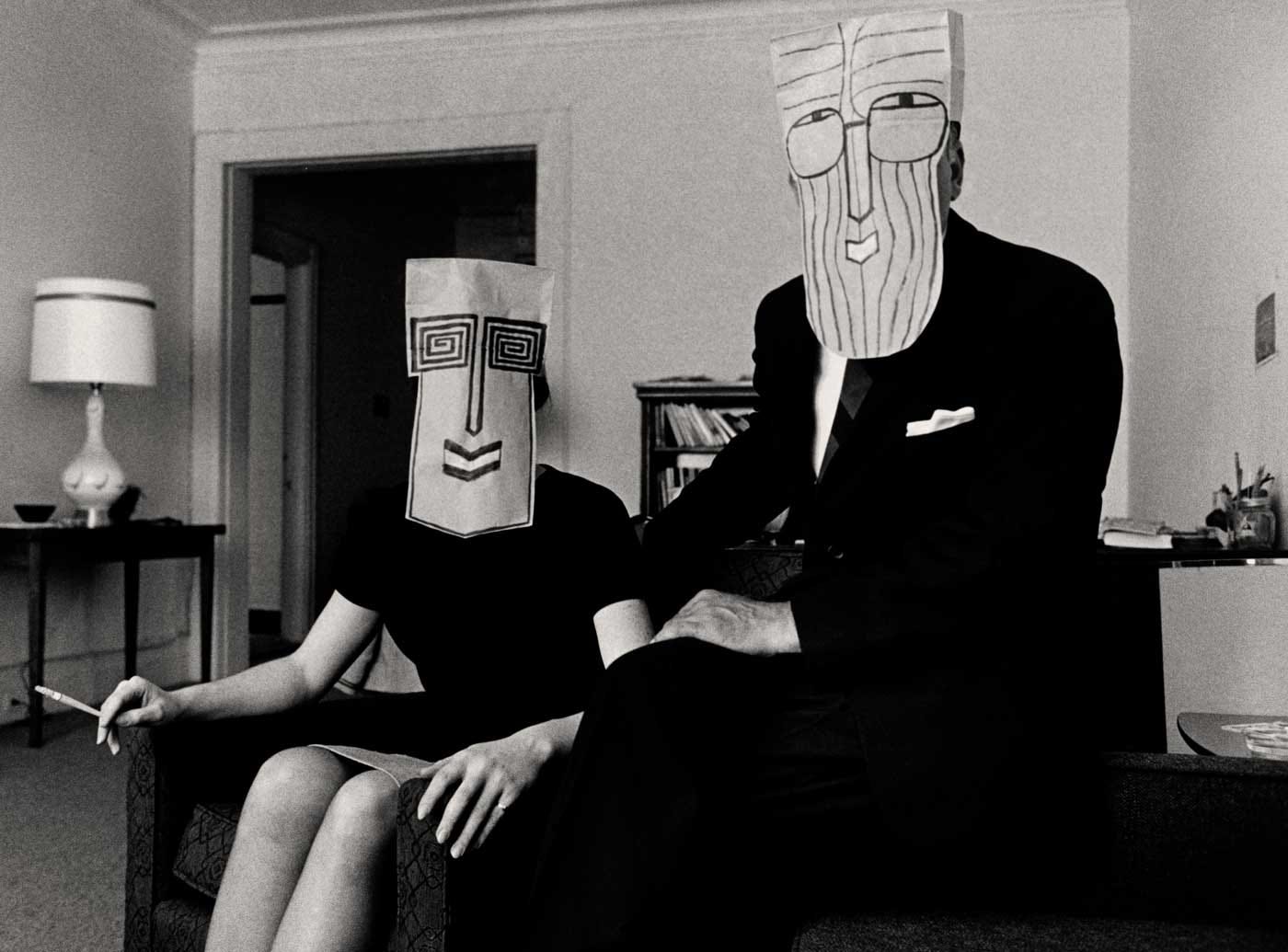

But again, ‘cancel culture’ does not come down from above, via institutional decree. Certainly, institutions do punish heresy with ostracism and absurdities like ‘hate speech’ are now being written into law, and, as always when prohibitions on speech become so encoded, these are abused by power to silence crimethink. Nevertheless, the compulsion to speak an antiseptic unlanguage, stripped of implication, does not come primarily from leftist snowflakes, but from the wider postmodern culture they speak for, a culture in which words cannot refer to or imply anything more real than moral consensus and, what’s more, in being entirely self-referential, take on the status of reality itself. Language, in postmodern thought and culture, only means itself, which is why critical speech, words which attack the ideas or beliefs of another, is conflated with actual violence, and why the act of telling the truth is defined as literal terrorism. Postmodern man is nothing but a self-definition, an ‘identity’ or mask. Because he has no contact with any reality from which to experience a sense of self which transcends the spectral sameness of this masklike identity11 any idea which questions it is existentially speaking, no different to a punch in the face.

For postmodern thought there is no reality, no consciousness, no meaning, except — a contradiction which the postmodernist simply waves away — the assertion that there is none. This again is not primarily a matter of overt indoctrination or cultural infiltration from the woke police, but an automatic consequence of our postmodern existence, in this case the breakdown of boundary and limit, which the highly developed technological system, which has no use for the borders the same system required to build itself, forces upon us. Distinctions which separate states, institutions, genders and people — including the border between my subjective self and the objective world — must be broken down by an increasingly virtual system which is hampered by them, leaving a kind of apocalypse of meaning, reflected in the absurd ideologies and senseless languages of the postmodern system.

For Orwell the dissolution of distinction was, as with the rest of Newspeak, a simple, localised affair, enshrined in his famous party slogans, ‘War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength,’ prototypical examples of what he called ‘Doublethink’, the ability to hold two contradictory political ideas in one’s mind at the same time. For us, who live in a postmodern world which is far more dystopian and disabling than Orwell’s12 limit-and-logic evaporating ‘Doublethink’ extends well into our social and personal lives. We live a pseudo-reality in which ‘public is private’, ‘man is woman’, ‘fat is thin’, ‘man is the machine’ and ‘reality is unreality’.13 It is then a small matter to make criticism of such statements verboten. Assertion of any kind of distinction in a world of indiscriminate cultural or psychological mush becomes indistinguishable from the ravings of a Nazi.14

Despite the strictures imposed by postmodern doublethink and top-down censorship, it is first and foremost the ‘tyranny of public opinion and feeling’15, which rules over the menacing barracks16 that classrooms have become, which silences Wrongthink in academic discourse and which prevents any book which questions the manifest moral certainties of Wokechurch from even being considered by a literary agent, let alone published or reviewed. Those who punish thoughtcrimes do not need to consult the will of the leader, all they have to do is what ‘feels’ right. This feeling is an internalised sense of what the group is likely to approve of, an approval which has taken the place where morality, dignity and integrity used to be. There is no need to overtly compel people to fall in line with such groupthink when the prevailing experience of reality is that there is no internal state upon which moral reasoning can be founded, and that, therefore, one must constantly be on the feel for consensus; for who we are allowed to laugh at today, for who the bad guy is now, for who currently deserves our charitable compassion. This goes a long way to explaining why a great deal of outrage, offence and cancellation, so often seems to happen on behalf of someone else. I am not offended, but the mythical ‘we’ might be.

Just as woke Neochurch is one institution within the overarching hegemony of Newchurch, which spans the right and the left, the sciences and the humanities, the West and the East, so the contradictory, doublethink of Wokespeak appears to be in opposition to the consistent, monothink of Technospeak, or scientism, but both are complementary parts, or poles, of the same Neospeak. Both Wokespeak and Technospeak are divorced from consciousness and context, the union of which allows us to experience the other as an actual quality of event, and so both dissolve into Neospeak literalism, either the dreary x = x of outraged Wokespeech or the smug, cheerless hyper-logic of Technospeech. Those who favour the latter are as unable as those who speak the former to grasp the elusive undermeaning of speech, the marriage of difference — self and other, man and woman, child and adult — from which true, instant, empathic understanding emerges and upon which our words are just a pretext. This is why both the pomotron and the technocrat see, in the miracle of communion, nothing but the ghost of themselves, reflected in the face of the enemy. Just as the fabulous ‘creative’ who considers herself above mere fact takes appeals to reason and reason as an inhuman, quasi-fascist constraint, so those who insist on the primacy of the rational fact take the chaos and hyperbole and paradox of free speech as artistic pretension.

Postmodern Wokespeak and the Technospeak of scientism then are both, ultimately, the same. The former robs speech of its reason,17 the latter of its unreason, but both rest on the same illusion, that speech and an abstract meaning, or intention, are somehow distinct when they are, as Steven Knapp and Walter Benn Michaels argued in their seminal essay of 1982, the same thing. The only possible meaning of speech is what the speaker intends, not because that intention lies ‘behind’ the words, but because it is the words. They are one and the same. While the scientist separates them out and declares there is one, true, meaning which we must find in the mind of the speaker (or author), the postmodernist separates them and declares that intention does not exist, that meaning is therefore socially constructed. The world of theory, for all its utility, collapses under the unacceptable simplicity of speech, just as it does under the unacceptable reality of phenomena.

The fundamental identity of the objectivist and the subjectivist is why the ‘wildest’ artists and the most ‘serious’ scientists both look and sound so similar — like managers — and why they speak the same abstract, literalist language, the only form of communication that can be understood in a highly developed machine system made up of isolated concepts. Modern scientists and modern artists, superficially at odds, possess the same artificial intelligence as that of the machine which they create and which creates them; which is why AI is capable of perfectly emulating their work, either artistic or scientific, and why it will soon supersede both.

AI is just as incapable of understanding that which is imprecise, polyvalent, non-literal and real (rather than fancifully invented), as its fleshy appendages, the soft machines we still mistakenly call modern people. Neither machine-man nor man-machine can make meaningful metaphor,18 unless meaning is already present. Although we will soon be watching artificially generated films, listening to artificially generated stories and reading artificially generated books, almost nobody will know or care, deprived as their lives are of genuine, living content. The metaphors we find in our new artificially generated unculture are empty, dead, reconfigured clichés or meaningless arrangements of words designed to remind us of what we already know, rather than to express the genuinely new; but we won’t care, because the unknown and the unknowable have been excised from our lives, like an ugly mole.

A final point. Speakers of Technospeak and Wokespeak are also alike in their astonishing lack of courtesy. Neither can perceive the actually existing but unspoken and unspeakable ground that we, you and I, share, and so neither feel the need to reach for the common-or-garden form of metaphorical speech we know as courtesy to express it. Courtesy is not the spontaneity-suppressing social and linguistic manners of the middle-class, the ‘correct’ way of eating or the ritualised language which that most dangerous class of human being, the polite man, hides his heart behind. Courtesy, insofar as it is a spoken, refers to delicacy and sensitivity as expressed, naturally, in understatement and implication. ‘Sorry, could I just squeeze past?’ does not mean ‘sorry, could I just squeeze past?’ It means ‘I am aware of your presence on earth, and do not wish to impose myself on it.’ ‘That’s a bit inconvenient’ does not mean ‘that’s a bit inconvenient’. It means ‘that’s a totally unreasonable request, but I don’t want to embarrass you by drawing overt attention to it.’ (Women tend to understand this better than men, and to feel the slow death of courtesy more acutely.) As meaningful metaphor becomes a forgotten myth, so do all the unnecessary decorative and hyperbolic aspects of speech, the curlicues and flourishes that we doodle over the things we say to each other, that we use not to literally say something, but to remind each other of our humanity, without having to lower ourselves to saying exactly what we merely mean.

Part 2 (of 4), Plastic Language, is here. Part 3, The Humiliation of Speech is here and part 4, the Final Word, is here.

For further discussion of the nature of metaphor, see Self & Unself.

George Orwell, 1984

Ibid.

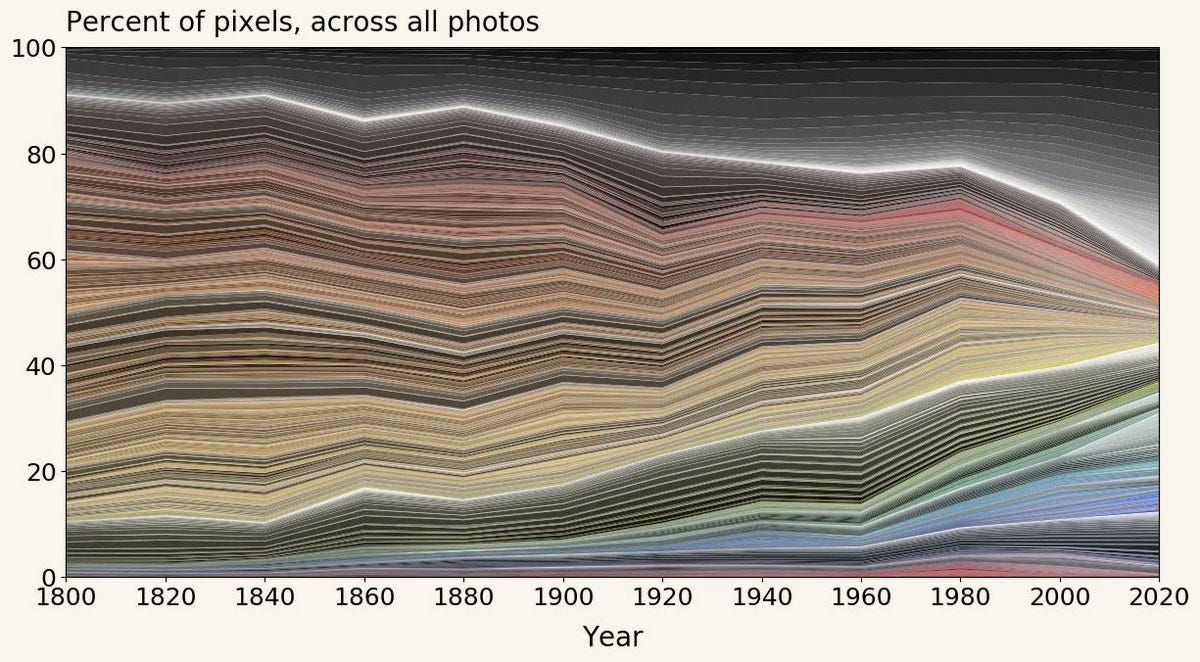

‘Dozens of words for shades of perception have disappeared from usage. For what the nose does, someone has counted the victims: Of 158 German words that indicate variations of smell, which Dürer's contemporaries used, only thirty-two are still in use. Equally, the linguistic register for touch has shriveled. The see-words fare no better.’

Ivan Illich, Guarding the Eye in the Age of Show

Changes in the colours of objects since 1800, from pictures of 7000 objects in the collections of UK science museums. Grey is winning, and not just in science museum artefacts. Colour is being drained from cars, clothes, walls, superheroes, shops, all of which tend to the desaturated, the monotone, the grey, which also predominate, analogously, in taste, smell and sound.

See Colin Turbayne, The Myth of Metaphor

Ivan Illich, The Scopic Past and the Ethics of the Gaze. Something similar happened to the Hindu gods of the Vedas, although India never had the same ‘analytic’ drive as the ancient Greeks.

Turbayne’s expression.

Nor are we conscious of the unreal world. Consciousness is reality, and follows us into dreams. To the degree that we can remain conscious we can, as it were, ‘enclose’ one experience and draw it into metaphorical union with another, a skill vanishing as rapidly as joinery.

The drive toward the formation of metaphors is the fundamental human drive, which one cannot for a single instant dispense with in thought for one would thereby dispense with man himself. The drive continually manifests an ardent desire to refashion the world which presents itself to waking man, so that it will be as colorful, irregular, lacking in results and coherence, charming, and eternally new as the world of dreams. Indeed, it is only by means of the rigid and regular web of concepts that the waking man clearly sees that he is awake; and it is precisely because of this that he sometimes thinks that he must be dreaming when this web of concepts is torn by art.

Friedrich Nietzsche, On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense.

Ivan Illich and Barry Sanders, ABC: The Alphabetization of the Popular Mind

And forms the political base of left wing political parties, who abandoned the trade-union movement. See Norman Finkelstein, I’ll Burn that Bridge When I Come to It.

From Mary Harington, Mystifying the Appearances.

The word ‘identity’ once referred to the Latin concept, ‘idem’, or sameness, and the word ‘mask’ has its origins in the Latin for spectre.

Incorporating, as it does, features foreseen by Aldous Huxley — technophilic permissiveness — Franz Kafka — schizoid arbitrariness — and Philip K. Dick — nightmarish virtuality. See 33 Myths of the System.

Slavoj Žižek is a fan of this kind of surface faff; ‘Love is evil’, ‘Hitler was a Jew’, ‘Ghandi was more violent than Hitler’ (or ‘Hitler was not violent enough’). Note though that these are boundary-dissolving contradictions, which are purely thought forms, as opposed to paradoxes, the kind that, say, Oscar Wilde excelled in, which refer to an actually existing mystery.

Or as the father of postmodernism, Jacques Derrida, put it, ‘Logocentrism… is the most original and powerful ethnocentrism,’ which is to say prioritising truth — qualitative or quantitive — is really a form of racism.

John Stuart Mill’s phrase.

Norman Finkelstein, I’ll Burn that Bridge When I Come to It.

This partly corresponds to the power that women now have in the system. Feminists occasionally voice the hope that the world, when it is run by women, will thereby realise feminine virtues, such as compassion and sensitivity. What actually happens is that an insane world can only privilege feminine vices, such as an inability to reason in a detached manner (without taking criticism personally), which then, as women gain power within the system, become institutionalised.

Or even meaningful utterances. There is no intention behind the ‘speech’ of AI, which means it cannot be meaningful, because it cannot be language.