Read Part 2, here.

Introduction

Among the multitude of scholars and authors we feel no hallowing presence; we are sensible of a knack and skill rather than of inspiration.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Over-Soul

When I have waded through one of these books its insipid descriptions and interminable harangues go instantly out of my mind, and the only impression that remains is one of surprise that a man can write three or four hundred pages when he has absolutely nothing to reveal to us—nothing to say!

J.K. Huysmans, Là-Bas

It’s not difficult to find great writers skewering their contemporaries. Similar passages can be found in Shakespeare, Fielding, Dickens, Schopenhauer, Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, Lawrence, Miller, Orwell and many others, complaining that charlatans and hacks dominate the world of letters, that beneath literary sentiment and pretension there is nothing, there is nothing, there is nothing.

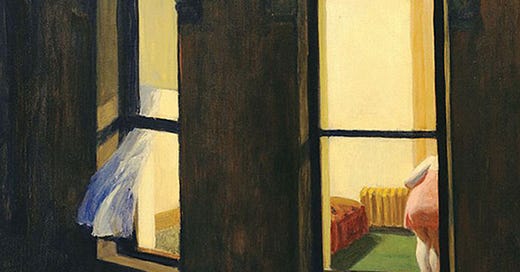

And nothing has changed. Pick up a book in the display section of Barnes & Noble, Foyles or Fnac and then pick up another, and another, and another, and it’s all the same. Like ready meals in a posh supermarket, it all looks the same, feels the same, tastes the same; the same concerns, the same approach, the same style, the same content, the same reviews, even the same covers. In non-fiction a single point, which could have been condensed into a paragraph, is strung out for a whole chapter, with irrelevant details, ideological niceties and tedious personal reflections filling up the page like undigested cellulose. In fiction, pages and pages go by without any real plot development or, if plot is not central, any entertaining or insightful episodes.1 There is nothing.

There is a frustrating weightlessness to published literature, because so little of it traces its pedigree back to the senses, for the simple reason that the senses of the author do not function properly. They’ve been amputated by their senseless lives. The literary second-rater has no real interest in ‘sensual communion’,2 no capacity to lay wide his soft-conscious attention in order to absorb the strange quality of the moment, the hidden subtleties of life or the unspeakable understory being played out in the world behind the world. Reality, the sensate reality of life as it is, is always out of fashion for the literary mediocrity, or out of reach, and so he must instead focus on subjective imagination (‘synthetic hallucination’—whatever he can merely think up) or objective reportage (the isolated—and therefore arbitrary—facts of experience). This will ensure that what he writes has an air of, on the one hand, magic, wonder, creativity or, on the other, hard-hitting truth-telling factual accuracy while, actually, being imitative, dull and fundamentally misleading.

Characters in books are interchangeable because characters in the world are.

The conscious reader gets a curious sense, from both ‘hard-nosed’ non-fiction and from ‘transcendent’ creative fiction, that, actually nobody is really there. The I—the passionate I—is absent. In the case of non-fiction, with the popular science or self-help book, the political ‘call to arms’, the philosophical tract or the authoritative history, there is no sense whatsoever that the author is passionately involved with the truth he or she is presenting, no sense that the author’s life or consciousness—the source of meaning, after all—can bring anything of vivid import to the question. With ‘literary fiction’, there appears to exist, on the contrary, an extremely personal ‘voice’, one that oh, bloods and smokes its heart-truths like a confusion, like a darkness, like an old, wet loaming (and so on and so forth), yet this narrating persona is paper thin. Underneath there is no sense that the author is passionately realising a recognisable truth, there is no distinct context, no recognisable society and no vivid, living characters, who speak and think individually.

Perhaps you have noticed this in myths and stories? A strange tendency for superheroes of the future, speaking seagulls, five-year-old children, ancient tribes-people and alien mind clouds—to say nothing of ordinary people—to all speak like comfortable middle-class graduates working in the entertainment industry? Or fifty year old tenured academics? Perhaps you have heard the neck-clenched mono-voice which speaks in the bestsellers and literary prize winners—the same voice you hear on the radio, on the television, in the newspapers…?3 Or maybe you’ve had the uncanny sense that all of the characters in a story are interchangeable. They speak the same, they feel the same, if they didn’t have different names, skin-tones and a few bolt-on quirks (or, in drama, weren’t played by different actors) you’d never be able to tell the difference between them, certainly not from their speech.4

The ‘mono-character’ can be traced back to the unreal, discarnate awareness of ‘creatives’, living in an abstract, mechanised world. Characters in books are interchangeable because characters in the world are.5 Meaning in literature does not exist as unique quality, which inheres in people, but as a series of unconscious urges or political ideas which float disconnected above existence like a parade of mythical flying machines. ‘Seriously’ reading literature today means, first of all, breaking it apart (‘deconstructing’ it) in order to reveal the fact that the author ‘really’ wants to be sodomised. The shallow socialist version of this professional pursuit for a spectral ‘unconscious’, that what the author ‘really’ intends is nothing more than a condition of social antagonisms, is the second component of professional discussion of literature, where even to speak of ‘character’ marks one as a hopeless fuddy-duddy, while to speak of the intention6 or character of the author, as expressed in his work, is beyond the pale.7 Literature today, like the modern conversation it seeks to justify, is seen as an exchange of text messages, a collection of word-things without reference to anything real at all. Real!? Hahahaha—you fascist! There is no ‘real’, didn’t you know? There are just words.

Observation and Metaphor

Another conspicuous lack in the literary wasteland—and another consequence of the unspoken belief that meaning resides in words alone—is original observation; aphoristic reflection on life as it is, on people as they are. There are no ‘that’s so true!’ moments of recognition in the modern novel8 or work of non-fiction, no quotable quotes, no sharp aperçus, no interesting insights into human nature. Compare a celebrated novel of today, something by, oh I don’t know, Toni Morrison, Philip Roth or Ian McEwen,9 with, say, Honoré de Balzac, one of my favourite authors and far superior, I believe to Dumas, Zola and Flaubert. Here are a few quotes, far from exhaustive, selected from one of his books… Pere Goriot.

…one of the most unattractive habits of Lilliputian minds is to imagine that others share their pettiness.

According to the logic of the empty-headed, who keep nothing secret because they hold nothing sacred, those who keep themselves to themselves must have something to hide.

Mademoiselle Michonneau kept her eyes lowered, not daring to look at the money, for fear of revealing how she coveted it.

Maxime, looking searchingly at him with that melting concern which betrays a woman’s secrets without her realising.

However gross a man may be, the minute he expresses a strong and genuine affection, some inner secretion alters his features, animates his gestures, and colours his voice. The stupidest man will often, under the stress of passion, achieve heights of eloquence, in thought if not in language, and seem to move in some luminous sphere.

Eugène was smouldering with that suppressed rage which drives a young man to plunge still deeper into the hole he has dug for himself, as if he hoped to find some way out at the bottom.

The open drawers of his brain, which he had banked on finding full of wit, slid shut, his aplomb deserted him.

Rastignac had one of those heads packed with powder which explode on the slightest impact.

I could go on.10 You might wonder how modern writers can read this list, let alone a book by Balzac (or by Kafka, or Sōseki, or Nietzsche, or Dickens), and not feel an anguished impulse to set light to their oeuvre, but it’s simple to explain; they just don’t read such books, or if they do, they feel the truth of them, because they can’t really feel the truth of anything. Their ‘Lilliputian minds’ may swoon at a few favourites,11 but on the whole they see nothing but their own pettiness in the majesty of great writing. Reading the above excerpts the modern author feels the same way Madame Vauquer would in the company of Anna Karenina; fawning adulation, supercilious lack of interest or open contempt.

This helps explain another feature of third-rate writing; empty or shallow metaphor. I suggested above that ‘subjective imagination’ and ‘objective reportage’ are really the same in that both indicate flight from reality, rather than reconciliation with it. This, the fact that literary mediocrities have to combine dreary, literal, materialism with equally dreary, but equally literal, idealism12 accounts for the notable lack of vivid, living metaphor, expressing recognisable depth, that one finds in their output. The writer has no access to an actually existing reality which eludes the literal mind—which miraculously unites objectivity and subjectivity—and so he has no instinct to express such panjectivity in meaningful metaphor.

I’ll explain. In great literature two different things are compared to show us a real and recognisable, albeit enigmatic quality they both share. Take another look at the last three of the Balzac quotes above, which use digging a hole, a chest of drawers and a bag of gunpowder to express recognisable human qualities. Compare these images with those in the metaphors of celebrated modern literature, where, instead of an actually existing quality being revealed through two concrete images, one thing is compared with a signpost for quality, an advert for depth — ‘the air is raining messages’, ‘blood spilled from his skull like a secret’.13 Unlike ‘his head was packed with gunpowder’ there is a kind of smeared vagueness about these comparisons, a wearying lack of actual content, which is why they are swooned over by people whose lives lack actual content.

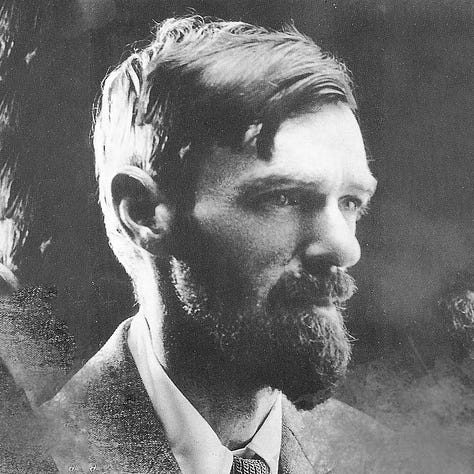

Not that, I should add, metaphor should be as sturdy and sensible as Balzac’s.14 He was, after all, a sensual realist, and therefore on the opposite pole to, say, J.K. Huysmans, or D.H. Lawrence, or Philip K. Dick who were also realists (as all good novelists are15) except that they perceived and expressed the unfathomable mystery of matter and so used metaphor more liberally, and most experimentally, than Balzac or, to pick another conspicuous example, Tolstoy, who, despite being a brilliant ‘metaphorist’ is, like most realists, disposed to metonymy, to expressing quality through association (through what a character wears, or how pink his skin is, and so on) and so will go for many pages with barely a ‘like’, and very few flamboyant images.

Nowadays the realism of Tolstoy and Balzac is out of fashion. Celebrated books of the materialist professional class are saturated with metaphors, but these have no real, profound meaning; ‘snow keeps falling, like a ceaseless repetition of the same infinitesimally small mistake’.16 Such writers telegraph depth because they have no idea what depth, which is to say what reality, actually is, which is why modern writers produce and applaud metaphors which do not refer to actually existing qualities. To take an example of a metaphor which does, and which is the complete opposite of Balzac’s solid style, try the following famous passage, from one of his near contemporaries, Comte de Lautréamont.

He is fair as the retractility of the claws of birds of prey; or again, as the uncertainty of the muscular movements in wounds in the soft parts of the lower cervical region; Of rather, as that perpetual trap always reset by the trapped animal, which by itself can catch rodents indefinitely and work even when hidden under straw; and above all, as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella!17

Here, as befits a decadent stylist, the relation between image and referent is extremely, even comically, remote, but it is still sharp and distinct. An actually existing quality, the character of a young man, is being revealed by the contrast between sensory phenomena,18 even if the contrast is wildly, madly, clashing. With the ‘her knickers smelt like sacrifice’ school of prose, we are not given access to any quality at all, but are being told to be impressed by it, a kind of literary despotism, not much different from a teacher telling children to be impressed, or to be good.19 Naturally enough, people who spend their lives in schools have no problem with this kind of thing.

More ‘muscular’ writers will avoid the silliness of ‘his mouth was full of bigness and importance’20 and reach for more trivial, nakedly clichéd, comparisons, ‘like a dog,’ ‘like a snuffed candle’, ‘like the dawn’, while true highbrows, authors of Serious Fiction, will wow us with images which make no sense at all, something like ‘the sense-captive mother-sense of petrichor’ or ‘his lips stood like proud herons over her crumb-clustered doubt’.21 After a few pages of such bonkers imagery, the kind that set serious critics’ eyes bulging, the reader actually ceases to think about what words mean and becomes numb to genuinely poetic language—which is precisely the point; Lilliputian minds like to be mystified.22

Put on some wellies and take a wade through the following passage, from Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses;

While inside the vaulting of the ribs between his knees the darkly meated heart pumped of who’s will and the blood pulsed and the bowels shifted in their massive blue convolutions of who’s will and the stout thighbones and knee and cannon and the tendons like flaxen hawsers that drew and flexed and drew and flexed at their articulations of who’s will all sheathed and muffled in the flesh and the hooves that stove wells in the morning groundmist and the head turning side to side and the great slavering keyboard of his teeth and the hot globes of his eyes where the world burned.23

Compare that with a passage from Laurie Lee’s Cider With Rosie. On the face of it, just as florid and sensuous, but God what a difference…

Never to be forgotten, that first long secret drink of golden fire, juice of those valleys and of that time, wine of wild orchards, of russet summer, of plump red apples, and Rosie’s burning cheeks. Never to be forgotten, or ever tasted again…

I put down the jar with a gulp and a gasp. Then I turned to look at Rosie. She was yellow and dusty with buttercups and seemed to be purring in the gloom; her hair was rich as a wild bee’s nest and her eyes were full of stings. I did not know what to do about her, nor did I know what not to do. She looked smooth and precious, a thing of unplumbable mysteries, and perilous as quicksand.

I can only hope, dear reader, you can see that ‘the great slavering keyboard of his teeth and the hot globes of his eyes where the world burned’ is at best a ludicrous caricature—this is supposed to be a majestic, sinewy who’s will incantation of who’s will; then Goofy walks in—and at worst an empty signpost for depth (we are, after all, talking about a domesticated herbivore24). ‘Her hair was rich as a wild bee’s nest and her eyes were full of stings’ on the other hand, conveys specific, sensate quality and, unlike the jarring clash between ‘keyboard-teeth’ and ‘hot-globe-eyeballs’ has an elegant, poetic ‘bee-themed’ (itself consonant with summer) consistency, of a piece with the woman herself. Those unacquainted with their senses are, alas, unlikely to see my point.

Not that sensuality does not figure in the poetry of celebrated writers who, one notices from reading five star masterpieces, is cover-to-cover packed with metaphorical descriptions of sensory experience. Here we come to another kind of metaphor, not one that expresses any psychological depth, which the mediocre writer has no real experience of — hence ‘her smile was like a mystery’ — but confines itself instead to sensual impressions, to the relatively shallow qualities of material experience.

The best of such ‘shallow metaphors’ are of course as lovely as they are necessary (‘I felt like a wind sock on a windless day.’ or ‘Elderly American ladies leaning on their canes listed towards me like towers of Pisa.’25), and in the hands of a master, rich with meaning (such as, in Great Expectations, Wemmick’s ‘letterbox mouth’26) but, like the work of the cynical king of empty sensuality, Gustave Flaubert,27 what we are getting here is not actually insight into the depth of experience, but its material surface. Like cooking, this is difficult to do well, but it’s extremely easy to do well-enough, which is why so many books are stuffed with this kind of thing;

The wood duck flew away. I caught only a glimpse of something like a bright torpedo that blasted the leaves where it flew. / I sit on the downed tree and watch the black steer slip on the creek bottom. They’re a human product like rayon. They’re like a field of shoes. They have cast-iron shanks and tongues like foam insoles.

Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

There circled two black hawks about the sun slowly and perfectly opposed like paper birds upon a pole. / They crossed a vast dry lake with rows of dead volcanoes ranged beyond it like the works of enormous insects. / Far out on the desert to the north, dustspouts lurched onward like some drunken djinn.

Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

And so on and so forth. Literally hundreds of thousands of examples of the same sort could be extracted from modern texts, pulled from them like bones from a small fish, like splinters from a schoolboys fingers, like rotten teeth from peasants’ heads, like sandworms from receding shorelines (you see? It’s really not at all hard; it’s nothing like doing what Balzac does, which require more than just looking at things and thinking of other things they look like). But in any case, this is all okay, books should describe things, but, as I say, this is trivial stuff, language as food, a trick of the light, like the photorealistic still-lives of the Dutch masters, which replace artistic truth for saliva. Our eyes widen, our heart races, we eat the meal, and then we forget the meal and hunger for more. This is quite different from the delight that an apperceptive depth-metaphor, one that reaches beyond appearances, provides the reader.

Style, and its Absence

Empty and shallow metaphor aren’t, of course, the only tricks used by writers to conceal the emptiness of their work. Others include;

Sloppy, sleazy, oozy, fat, dribbly, darkening adjectives in their straining, creaking, crunching, chunky, glistening cartloads; ‘gentling the gleaming dirigible’, ‘like a drug dripped down the spiraling canals of their ears’ and so on and so forth.28

Porn of any kind. Decadent imagery, food, celebrity tittle-tattle, explicit sex, horrendous violence, and ‘controversial subject matter’, but not too controversial, at least nothing that might diminish one’s chances of appealing to a ‘demographic’.

A common form of porn, found in lowbrow literature, is sentiment. This might appear as the queen of pornographic allusion, nostalgia, or the author might prefer titillating references to shared knowledge, such as sequels full of in-group, fan-servicing allusions to part one.

Sentiment is the holiday of cynicism, another favourite of the literary second-rater. Simply write a book, or a series of books, that expresses nothing but nihilistic despair, hatred for life and endless, bickering finger-pointing at them, and you can be sure of a decent return.

A trick favoured by women authors, particularly those who aspire to the coveted status of ‘literary it-girl’, is to spend 40,000 words over-sharing. Like the secretary at work, you might have nothing to say about existence, but we still want to know all about how the guy who broke your heart can’t get it up.

Related to this, although sometimes a little more difficult to spot, is to tell the reader what the novel is all about, the significance of what has happened and what is going to happen. This gives [stupid] readers a nice reassuring feeling that they get what it’s all about.29

That said, all authors, men and women, can find an easy route to literary success through the cheap genre of confession, appealing to the salacious curiosity of the reader by presenting their own experience undigested, without filtering it through the craft required to make great art.30

Excessive literariness and pointless difficulty also finds a paying audience. Books full of classical references, for example, or arcane language, serve the same function as quiz shows do for lower sorts, as a consoling justification for a mind full of useless knowledge.

Formal experimentation is also very important if you have nothing much to say. Make it impossible to work out which character is speaking, or when,31 or omit all punctuation, or write the book backwards, and your vacuity becomes harder to identify — but much easier to identify with.

Postmodern techniques are also popular today; demolishing the fourth wall (the author appears as a character, the characters remind you they’re not real,32 Darth Vader swans in, etc.), or cross fertilising stories with characters from other books, or random rather than revealing onions and ninjas.

A pomo favourite is hyperfocus on microscopic fragments of sensation, such as six pages on a shade of blue, or a shade of doubt. Reportage, the tedious minutiae of a character’s life, is another pomo staple, appearing in books and films as five minutes (or five pages) of a character eating a pie.33

Naturally, none of these things are really bad in themselves. All great literature employs such tricks to some degree, to embellish or even to express artistic truth. The point is that they are all used, in substandard work, to conceal meaning, just as salt and sugar are with nutritionless unfood. Because quality—beauty, harmony, truth, love and so on—is so rare in most people’s experience, its absence is not really missed. The reader fans herself in breathless wonder at the slender, snaking, smokey poetry, she is titillated by references to lollipops she used to suck and she sobs at a heart broken just like her own, but, ultimately, she is left frustrated, as after a Big Mac. The world remains as it was before, if anything—as fraudulent artistic experiences tend to move the reader to feeling an satisfied up which always leads to a dissatisfied down—less alive than it was before she opened the book.

We are now speaking, in rather a broad sense, of good style, lack of which makes the literary landscape look much like the urban landscape that shapes it, a mixture of bleak, brutalist tower blocks and multicoloured perspex pop-ups; both aspects fronting nothing. Great writing also has two aspects, on one side a kind of transparency that lets the light of meaning shine through—Homer’s, for example, or Hume’s, or Tolstoy’s—and on the other, a more forceful, ‘stylised’ or individualistic ‘stained-glass’ that provides its own colour. Tacitus might be an example from the ancient world, Shakespeare from the early modern period and Proust from the modern era. All these writers seem, stylistically, to be very different, but both of the extremes they represent are expressive of something else, an artistic truth which, through the character of the writer, actually exists. By contrast, the prose of poor stylists, to stretch my metaphor a little further, resembles a muddy window, allowing no light through, providing no beauty of its own and, if you can get the thing open, looking out onto a car-park.

I don’t mean to say that good writers can sustain a good prose style from first to last, nor do they have to. ‘An imperial crown cannot be one continued diamond; the gems must be held together by some less valuable matter.’34 What’s more, unless you are James Joyce, lack of finesse and errors of judgement, like unconscious plagiarism, creep into writing like mites into furniture. Really only an obsessive can keep out every cliché, every tired metaphor, every ungainly repetition, every misuse of psychic distance, every misstep with register, every unmotivated shift in rhythm, every bizarrely structured sentence, every cloddishly irrelevant detail and all the rest of the gunk that clogs up amateurish literary expression. That said, great writing is about as close to faultless as man’s activity can reach and even errors contribute to its greatness. A good style is, like a good metaphor, careful, distinct and vivid,35 even when it is expressing enigma and disorientation, and poor writing is ragged, vague and shapeless, even when it is endeavouring to be hard-nosed and cowboy-fingered.36

This does not mean that good style is necessarily unique. One of the worst crimes a writer can commit, now so common as to be as universally accepted as practically every other crime, is to try and do what Joyce, Faulkner and company did and develop a style that is unlike anyone else’s. Ultimately uniqueness in literature comes from something far deeper than how an author presents dialogue, the point of view she chooses, her diction and register and so forth. A writer can use the same kind of omniscient authorial voice that Hugo and Dumas employed, that hundreds of other great writers have used, and produce a work that is still unlike any other on earth, rich with individual — not to mention universal — meaning. What tends to happen is the reverse, a writer comes up with a personal style, never seen before, and then uses it to write a book as shallow and meaningless as all the others that do the same.

There are four basic forms that poor style can take, pornography, sentimentality, frigidity and mannerism.37 Pornography, as noted, titillates the senses, and endeavours to substitute appetite, or excitement at its consummation, for genuine artistic truth. Sentimentality (as discussed here) pushes unearned emotion into the reader’s face, by waving around signs for depth, by having the book telling you that something is sad, moving, heart-breaking and so on, by appeals to unconscious animal instincts (‘ah, the puppies’, ‘consider the children!’ ‘dulce et decorum est pro patria mori’) or by reminding the reader of his or her youth. Frigidity is lack of seriousness, of treating one’s characters like pawns, like things, that can be manipulated in service of a plot, a message or a gag. And mannerism, which is a type of frigidity, and perpetrated by the same unfeeling criminals, is the use of literary effects, highfalutin language or downright obscurity to conceal absence of meaning or dramatic interest.

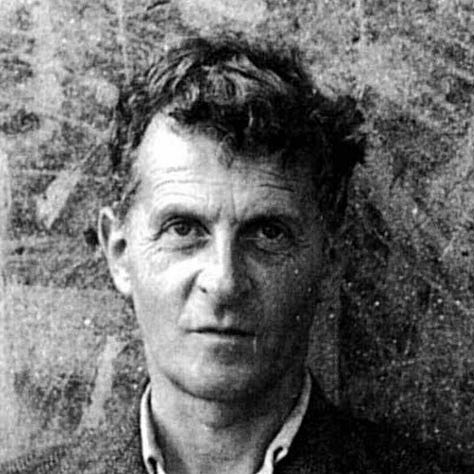

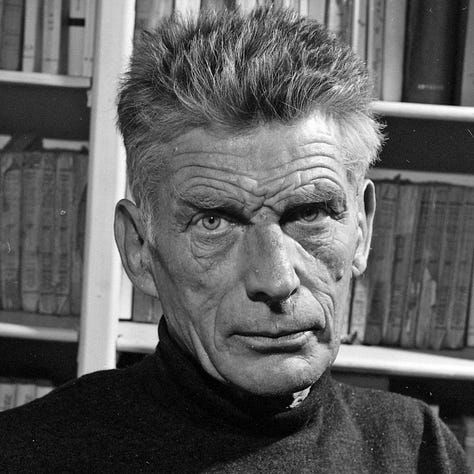

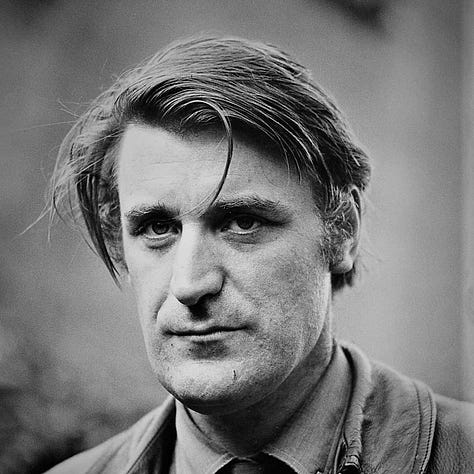

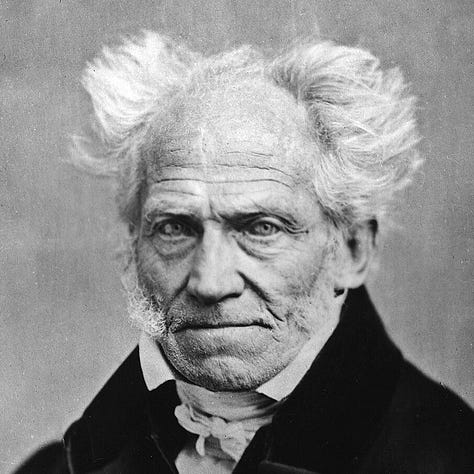

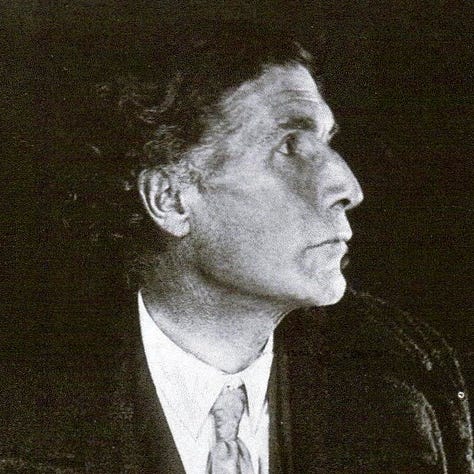

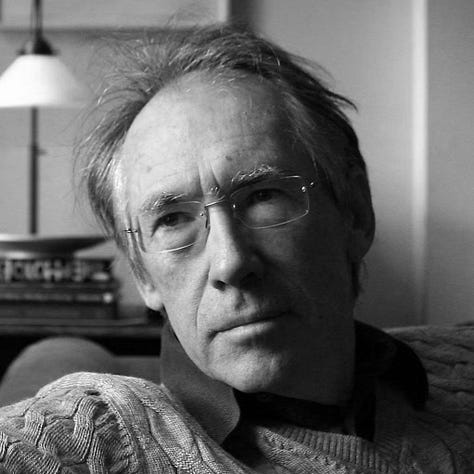

Nowhere, if you’ll excuse the oxymoron, is frigid, stylistic obscurity clearer than in modern philosophy, where mystification brought down to its murky nadir, because nowhere is it so necessary to conceal lack of meaning—confusion and triviality—with verbiage. Philosophers, taking their cue from the German godfathers of obscurity, Kant, Hegel and Heidegger, are only too willing to dress up nonsense or vapidity in baffling circumlocutions and impenetrable fiddle-faddle. Style, as Goethe, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche all realised, is the physiognomy of the author’s soul which, in the case of writers who do not want to be clearly understood, is not worth revealing. This is why the faces of modern authors are as bland as their prose. One need not look very deeply into the lives, or eyes, of writers who write without meaning to see that there is very little there to meaningfully speak.38

Writers of fiction are just as guilty of course. If one has very little to say it is imperative that one obscures this from both oneself and from one’s reader. The literary amateur will simply fill his books with porn and sentiment — with sex, violence, nostalgia, plucky whores, weeping mothers, supernaturally intelligent detectives and so on and so forth — but serious writers, who’ve been to university, or read some difficult books, will quite naturally choose excruciatingly convoluted syntax, clauses clustered upon each other like courses at a king’s banquet and all the Latinate words his thesaurus can offer in order to give the impression that here a writer is at work. Bizarre slips of register can give the game away here, but if he is careful he’ll maintain the illusion that he is very, very clever right to the end.

Logically enough, obscurantism is strenuously defended as somehow necessary in philosophical expression and serious fiction. Apparently it is impossible to express profound meaning in clear language—insurmountable opacity is the only form depth can take. Readers of Jacques Lacan and Thomas Pynchon might suspect that bad writing is just that, bad, or that highly literate writing, philosophical or otherwise, is difficult to understand because it is written by and for people who live entirely on the page. What such hopeless naifs don’t realise is that hyper-abstract speculation does not have to be interesting, relevant or clear, because only words matter in educated discourse.39

The reality that closely-inspected words once referred to is of diminished importance in modern Deep Thought, likewise the character of the writer, likewise his passions, likewise the context of the reader. Even the clarity of the text is irrelevant, because, as a text, it is always there to refer back to, to work out. This, you see, is what you are supposed to do with highly literate philosophy, as you are with ‘great’ literature; not listen to it, enjoy it, converse with it, apply it (albeit intuitively) to your struggle to live more intensely, no no no; you’re supposed to work it out, as you would five-metre square Sudoku puzzle. Actually this is reasonably good training for engaging with the world, which is an extremely difficult and purposeless puzzle, but for anything which really matters—love, life, death, truth, beauty—such an approach scorches what it affects to illuminate and imprisons what it pretends to set free. We get the meaning: but so what? So what?

Part 2 of this essay, focusing on the literary mediocrity, here…

Alternatively, a story will be all plot, all cleverness and message, but peopled with cyphers, people-shaped devices, without individuality, and so rarely described, and almost never located in anything like a ‘personal world’ or ‘life world’. See below.

Bad poetry always suffers from the same defects: synthetic hallucination and artifice. Invention is not poetry. Invention is defence, the projection of pseudopods out of the ego to ward off the ‘other’. Poetry is vision, the pure act of sensual communion and contemplation.

Kenneth Rexroth, Poetry, Regeneration and D.H. Lawrence

And not just in adult fiction. In textbooks, in children’s books, in instruction manuals, in classical music recitals, in powerpoint presentations, in office gossip; everywhere one hears this same tidy, comfortable, colourless, monitonal monomind.

We should note here that, as with maintaining good style, it is nearly impossible for an author to completely inhabit the language of his characters. Shakespeare doesn’t, Lawrence doesn’t, even the fastidious Joyce slips up and gives Bloom poetry far beyond his sensibilities. The point here is not that a good author colours his character’s minds, or occasionally intrudes into them, but that he allows them to live independently, as unique individuals, which mediocre authors cannot do, because they cannot even really perceive individuality, let alone know how to express it.

The world machine is comprised of human parts which, like every other machine, are interchangeable. This is why we find, for example, an unskilled worker is just as suited to working in a fish factory as a phone factory. Or, at the other end of the social scale, why a politician can become minister of health, then minister of defence, minister of culture, and do each job equally well (or equally badly). It doesn’t matter that he knows nothing of these things, any more than it matters that the wheels don’t know where the car is going. They just have to go round.

James Woods, in The Broken Estate, has this to say about the politicised postmodern denial of intention.

…a poem is the most delicate, the most realized form of intention there is. It is the quintessence of intention. To read it as if intention is always failed simply denies what is most distinctive about the literary: its intention-rich status. Without a rich idea of the achievability of a poem, the poem disappears as the poet’s achievement and becomes the reader’s negative achievement, or the epoch’s: for if a poem has a political unconscious, then it has been written partly by the political discourses of the age. This tendency is strong in New Historicism and cultural materialism, in which, largely, it is assumed that Shakespeare’s plays are conservative, because the age he wrote in was conservative. (Whatever that means.) Leonard Tennenhouse has argued that “Shakespeare uses his drama to authorise political authority, and political authority as he represents it, in turn authorises art.” That Tennenhouse can allege this about Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, two of Shakespeare’s most wildly rebellious plays, only shows Tennenhouse to be the true conservative. But then, such critics do not believe in radical texts; they believe only in radical readers, whom they fondly imagine themselves to be.

There is, in both fiction and non-fiction, a taboo on understanding literature not just as something produced by certain people but as a consequence of being the person that wrote it. This taboo is put in place by people who know they are nobodies. Of course ideas do stand alone and of course they are, to some degree, shaped by the unconscious and culturally determined, and it would be reductionist to confine works of art entirely to the nature of the author. But to rule out the author entirely (or his artistic intentions, or his interest in people) is to say, in effect, that books write themselves. No surprise then that the idea that the author is dead took hold just at the point when machines appeared which could replace him.

Unless of course you were raised in modern house, went to a modern university, then got a modern job—punctuated by a few modern holidays—and raised a modern family of your own. Then nothing happening for page after page after page seems like the acme of perceptive acuity.

A casual search for ‘greatest quotes’ of these three novelists results in gems such as these (I invite readers to direct me to profound aphorisms from these authors that I might have missed)…

Morrison: “Freeing yourself was one thing, claiming ownership of that freed self was another.” / “You are your best thing.”

Roth: “Stop worrying about growing old. And think about growing up.” / “Life is just a short period of time in which you are alive.”

McEwen “A person is, among all else, a material thing, easily torn and not easily mended.” / “Not being boring is quite challenge.”

You don’t say Ian.

It doesn’t end there though. Take a look at the jewels dropped by Paul Auster, Marilynne Robinson, Jon Fosse, Annie Proulx, Paul Kingsnorth, Anna Burns, Paul Lynch or any Pulitzer or Booker prize winner, or nominee, of the past three or four decades. I’m not saying that one has to be a master of the epigram to write well—a few greats weren’t—but the dearth of aphoristic insight, and the preponderance of ‘poetic truths’ along the lines of ‘Love is holy because it is like grace,’ or ‘Old things climb out of my mouth and set themselves free in the air’ or ‘Happiness hides in the humdrum’, is not because proverbs are out of fashion, but because there is not a single original thought in a single published head.

Some of these are not immortal insights of course — Balzac wasn’t very penetrating; nothing like Dostoyevsky, say, or Lawrence and he could certainly offer tasteless trivialities by way of observation (‘Happiness is the poetry of woman as make-up in their rouge.’ ‘Is not a sentiment a world in thought?’, etc.). Furthermore, as Eric Auerbach points out in Mimesis, he was ‘unable to create the true atmosphere of the higher spheres—including those of the intellect’. But Balzac himself understood all this; ‘I am not deep, but very wide, and it takes time to walk round me’. The point is that, unlike literary journeymen, Balzac constantly touches on universal truths.

In his characterisation too, Balzac could express qualities of ‘type’, that we can all recognise, and which we enjoy recognising, in specificities of individual character, packed with an energy which threatens to ignite the page and delineated with what today appears to be supernaturally observant care.

Take a read of the entrance of Madame Vauquer in Père Goriot…

Now the widow herself appears, shuffling along in her puckered slippers, a crooked hair-piece poking out beneath the tulle bonnet perched on her head. Her flabby, sagging face, her protruding parrot’s beak of a nose, her stubby, pudgy hands, her plump tick of a body, her overstuffed, wobbling bodice, are all entirely in keeping with this room, where the walls sweat misfortune, where enterprise kicks its heels and whose fetid fug Madame Vauquer breathes in without gagging. Her face is as cold as the first autumn frost, the expression in her crow-footed eyes shifts between the fixed smile of a ballet-girl and the baleful scowl of a sharper; in all, everything about her points to the boarding house, just as the boarding house leads to her. There can be no prison without a warder, the one is unimaginable without the other. The short-statured woman’s blowsy embonpoint is the product of the life she leads, just as typhus emanates from the vapours of a hospital. Her knitted woollen petticoat, drooping below an overskirt made from an old dress and poking out through the slits where the cloth has worn away, epitomises the drawing room, the dining room, the garden, anticipates the cooking and prefigures the boarders…

Auerbach analyses the above…

The portrait of the hostess is connected with her morning appearance in the dining-room; she appears in this centre of her influence, the cat jumping onto the buffet before her gives a touch of witchcraft to her entrance; and then Balzac immediately begins a detailed description of her person. The description is controlled by a leading motif, which is several times repeated—the motif of the harmony between Madame Vauquer’s person on the one hand and the room in which she is present, the pension which she directs, and the life which she leads, on the other; in short, the harmony between her person and what we (and Balzac too, occasionally) call her milieu. This harmony is most impressively suggested: first through the dilapidation, the greasiness, the dirtiness and warmth, the sexual repulsiveness of her body and her clothes—all this being in harmony with the air of the room which she breathes without distaste…

And so on. Obviously our tastes have changed since the nineteenth century, but how many novels today present characters as part of their ‘milieu’ in this way, how many have such a sense of unity? Indeed, nevermind Balzac’s mighty eye; how many show any powers of observation when it comes to human character, in all its embedded completeness and all its fascinating variation?

The BBC recently put out an unintentionally funny documentary series called, Jane Austen: Rise of a Genius. No, don’t watch it — I couldn’t get past twenty minutes myself (of three hours!) — I mention it because it’s a good example of shallow, frigid middle-class minds going all gooey at an equally shallow, frigid, middle-class author. Granted, Austen writes very well, technically, her books are very readable (I personally enjoyed Pride and Prejudice very much. Emma isn’t bad either) and her jaundiced eye is very often superbly observant, far more so than that of the authors she has ‘inspired’. But… genius !? There have been libraries written about three or four books that are, essentially, gossip. What, exactly, can you learn about human nature from reading Jane Austen? Mate selection is an economic algorithm, identity is a negotiated construct, and the British Empire is an offstage ATM for the gentry.

See Self and Unself.

These examples are taken from, respectively, Arundhati Roy, The God of Small Things and Richard Powers, The Overstory.

Nor even exist. Hemingway’s books contain hardly any.

The reason why so-called ‘magic realists’, such as Toni Morison, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Neil Gaiman, Jeanette Winterson and the like are so tedious (and so highly praised by tedious people) is not because they describe magical occurrences, but because their fantasy is just that, fantastic; a mere work of imagination. It does not express or describe a magical reality. The great writers of magical tales, such as Dante, E.T.A.Hoffmann, H.P. Lovecraft and Philip K. Dick are revered not because they are imaginative, but because they are so solidly realistic.

Sally Rooney, Normal People.

Comte de Lautréamont, Les Chants de Maldoror.

Even as it is with the most enigmatic metaphors of all, the kind that one finds in the Gospel of Thomas, in which Jesus is compared to what one finds in the space of a lifted stone, or in the Tao Te Ching, in which the Way is compared to the still centre of a moving wheel.

You know the types, the ones who say, ‘you’ve really impressed me.’

A few more metaphors which dissolve into crass stupidity when you actually think about them.

Long clean teeth jumped out like bayonets from ambush.

Clive Barry, Crumb Borne

Later, the smelting plant would fire up its chimneys and smoke would drift over the Franklin Mountains, which shadowed the city like a row of brown shrugs.

Steve Almond, My Life in Heavy Metal

I imagined a clean, hard, bright city, peopled with a special kind of crisp-edged girl with apple-crunching incisors and long, gleaming legs like lascivious scissors.

Angela Carter, The Passion of New Eve

His open mouth was an old sea-shell.

Michael Ondaatje, Coming Through Slaughter

Sunsets fell through the western sky, the colour of blood through a fistful of water.

Colum McCann, Songdogs

The girl’s face was as tight and mean as broccoli.

Toni Morrison, Tar Baby

B.R. Myers in his justly celebrated (and, naturally, hated), ‘Reader’s Manifesto’ lists the following example, from Annie Proulx’s The Half-Skinned Steer;

In the long unfurling of his life, from tight-wound kid hustler in a wool suit riding the train out of Cheyenne to geriatric limper in this spooled-out year, Mero had kicked down thoughts of the place where he began, a so-called ranch on strange ground at the south hinge of the Big Horns.

Myers follows this laughable rubbish with the following analysis:

Like so much modern prose, this demands to be read quickly, with just enough attention to register the bold use of words. Slow down, and things fall apart. Proulx seems to have intended a unified conceit, but unfurling, or spreading out, as of a flag or an umbrella, clashes disastrously with the images of thread that follow. (Maybe ‘unraveling’ didn’t sound fancy enough.) A life is unfurled, a hustler is wound tight, a year is spooled out, and still the metaphors continue, with kicked down—which might work in less crowded surroundings, though I doubt it—and hinge, which is cute if you’ve never seen a hinge or a map of the Big Horns. And this is just the first sentence!

Here’s another example, also from The Shipping News, of Proulx confusing literature for emptying a rubbish bin over a paragraph of prose…

A great damp loaf of a body. At six he weighed eighty pounds. At sixteen he was buried under a casement of flesh. Head shaped like a crenshaw, no neck, reddish hair ruched back. Features as bunched as kissed fingertips. Eyes the color of plastic. The monstrous chin, a freakish shelf jutting from the lower face.

When the Latin Bible was translated into vernacular, spoken languages of the congregation so that they could, for once, understand what the priest was saying to them every Sunday, many of them… complained!

Quoted in Myers (see note above). McCarthy, it should be obvious, I can’t stomach, but, as Myers recognises, his first few novels were restrained and readable, before he started with all his burning and sizzling and carving and boning.

Alright, yes, I’m being a little unfair here. Horses are indeed otherworldly creatures (rabbits too), but McCarthy’s evocation of this is both laughably trivial, with its shifting bowels, and absurdly overblown. Compare D.H. Lawrence, not one for restraint, describing a divine horse with what might seem to be with a similar touch:

What was it? Almost like a god looking at her terribly out of the everlasting dark, she had felt the eyes of that horse; great, glowing, fearsome eyes, arched with a question and containing a white blade of light like a threat. What was his non-human question, and his uncanny threat? She didn’t know. He was some splendid demon, and she must worship him… Looming like some god out of the darkness was the head of that horse, with the wide, terrible, questioning eyes. And she felt that it forbade her to be her ordinary, commonplace self. It forbade her to be just Rico’s wife, young Lady Carrington, and all that.

This is far less pretentious and overwrought — for no other reason than that Lawrence is describing the actual mystery of the horse, rather than a presenting an imagined creature, but I’m sure you’ve already decided for yourself, so I’ll leave it there.

These two from Nicholson Baker, A Box of Matches, and Vladimir Nabakov, Lolita respectively.

Note that this metaphor is repeated again and again in Great Expectations, just like Prince Andrew’s small hands are in War and Peace — as motifs.

Flaubert, despite being a shallow misanthrope, was of course a master stylist. Take these reasonably straightforward examples;

Les toits de chaume, comme des bonnets de fourrure rabattus sur des yeux, descendent jusqu'au tiers à peu près des fenêtres basses, dont les gros verres bombés sont garnis d'un nœud dans le milieu, à la façon des culs de bouteilles.

The roof-thatch, like a fur cap pulled over the eyes, hangs about a third of the way down the low windows, their thick bulging panes adorned with a centre-knot, rather like the bottom of a bottle.

…et cependant elle sentait toujours la tête de Rodolphe à côté d'elle. La douceur de cette sensation pénétrait ainsi ses désirs d'autrefois, et comme des grains de sable sous un coup de vent, ils tourbillonnaient dans la bouffée subtile du parfum qui se répandait sur son âme.

…and yet all this time she could smell Rodolphe’s hair beside her. The sweetness of this sensation went down deep into her past desires, and just like grains of sand in a puff of wind, they were swirling about in the subtle breath of the odours that were spilling down into her soul.

These are from Marilynne Robinson and Ann Patchett, but the habit can be traced back to James Joyce and Marcel Proust who were so addicted to poetically describing sensations they could spend three pages on sniffing a toenail.

This of course is a trap that all amateur writers fall into, telling instead of showing. ‘He was really angry’ instead of ‘he kicked the door’. It’s certainly not a rule that cannot or should not be broken, nor one that even the best writers don’t break by accident, but it’s a trap that dilettantes unconsciously fall into very easily, because it is so easy to tell your reader what to think and feel rather than have him actually feel. As C.S. Lewis put it:

In writing, don’t use adjectives which merely tell us how you want us to feel about the thing you are describing. I mean, instead of telling us a thing was ‘terrible,’ describe it so that we’ll be terrified. Don’t say it was ‘delightful’: make us say ‘delightful’ when we’ve read the description. You see, all those words, (horrifying, wonderful, hideous, exquisite) are only like saying to your readers, ‘Please will you do my job for me.’

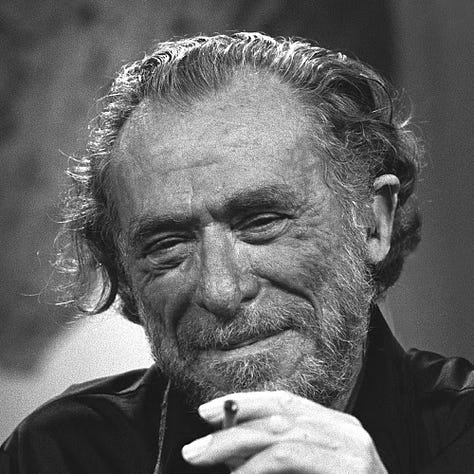

The confessional tract can reach great heights, such as in the work of Henry Miller and Charles Bukowski, but it is also an sitting duck for narcissist self-expression, as the fact that it is so very appealing to second-rate writers. Had a miscarriage? Fought alcoholism? Had an abusive mother? Struggled with your identity? Get writing babe!

This is the great appeal of modern novels, of which there are countless thousands, which ‘explore memory and identity’. Oh wow, so perhaps it never really happened.

This leads to weightlessness and triviality. We are no longer interested in what the characters can tell us about reality because all they are capable of telling us is merely whether or not they are real. It’s a little like sex scenes in films which are so realistic they do away with the fiction that communicates the meaning; we then stop being erotically—much less dramatically—interested in what is happening because now all we want to know—all we can really ask—is ‘oooh, are they really doing it?’

The traditionalist answer to the ‘innovative fictionist’s’ general line of argument might go like this: Innovative fictions of the kind just discussed are not inherently wrong-headed, merely unserious. Whatever interest or value they have they derive from their contrast with “traditional”—that is, “conventional” or “normal”—fiction. So long as conventional fiction remains adequate and worthwhile, innovative fictions are literary stunts. They have a kind of interest, as intellectual toys, but they engage us only for the moment. Though traditional serious fiction may also be play, since it deeply involves us with the troubles of characters who do not in fact exist, the play in serious traditional fiction bears on life, not just art. As we play at compassion, weeping for Little Nell or Ophelia, we exercise faculties we know to be vitally important in real life. If the assembly of made-up materials in a fiction creates a portrait of the artist, the importance of the portrait is not that it tells us what the artist looks like but that it provides us with a focus, an aperture, a medium (as in a séance) for seeing things beyond and more important than the artist.

John Gardner, The Art of Literature

Suffocation by sensory detail began with Gustave Flaubert, who opened up the world of the senses to the reader, but also paved the way veritable libraries of long, languid, buttery descriptions of knees and apples and butterflies and mother’s sighs and papery petticoats and on and on and on and on and on.

Flaubert’s tradition of hyper-sensuality made its way through the cold brilliance of James Joyce, then onto the decadent sensuality of Vladimir Nabakov, and the turgid pomposity of writers like John Updike and Richard Powers, before reaching its modern terminus in the ‘she stood up, scratched her chin, stepped forward, opened the window and looked out’ school of writing…

Marianne answers the door when Connell rings the bell. She’s still wearing her school uniform, but she’s taken off the sweater, so it’s just the blouse and skirt, and she has no shoes on, only tights.

Oh, hey, he says.

Come on in.

She turns and walks down the hall. He follows her, closing the door behind him. Down a few steps in the kitchen, his mother Lorraine is peeling off a pair of rubber gloves. Marianne hops onto the countertop and picks up an open jar of chocolate spread, in which she has left a teaspoon.

This is page one from literary it-girl, Sally Rooney’s blockbuster, Normal People. An indulgent reader might give the woman a little grace, she’s setting the scene perhaps? But no, the whole book is like this. Really it is. And her chums in the management-class press have the gall to mention her in the same breath as Joyce. A more fitting comparison would be Hemingway, but a Hemingway who had never done anything or been anywhere. Apparently in her recentmost, Intermezzo, she’s made an effort to sound more Joycean and has chopped up her sentences a bit and stuck in a few quotes from Hamlet. The Observer are impressed.

Dr. Johnston, The Lives of the Poets.

By which I mean characterful. One gets the sense, as Pascal put it, that…

When we encounter a natural style we are always surprised and delighted, for we thought to see an author and found a man.

However, there is, within the bounds style, a scale of what is technically called ‘decorum’, which means fitting one’s writing to a character. The scale runs from lyric poetry, which demands very little decorum — and so one hears the personality of the author in every line — to drama, which requires a great deal decorum. The author, unless he puts himself into the play as narrator, generally has to step out of it for characters to live as characters (even if they all inevitably express his soul anyway). Novels are roughly in the middle, which is one reason why a demand for ‘style’ from literary agents and publishers is often misplaced, as a perfectly transparent style is quite permissible in novels, sometimes desirable, unless of course you live in a decadent civilisation which has no use for anything other than the mask of personality, which must be present in every spoken and written utterance regardless of whether it covers a human face or not.

C.S. Lewis wrote, in Cross Examination, God in the Dock…

The way for a person to develop a style is (a) to know exactly what he wants to say, and (b) to be sure he is saying exactly that’.

…which helps us understand the horrendous style of modern writers, who are (a) never quite sure what they want to say nor (b) whether they are saying exactly what they mean (the correlative in normal life is the airhead who complains ‘I know what I mean but I just don’t know how to say it.’). This of course is why the meaning of their work is so difficult to fathom — because it’s not actually there.

This is a slightly expanded version of John Gardner’s ‘sentimentality, frigidity and mannerism’, presented in his admirable Art of Fiction, one of the only ‘how to’ books on writing that is worth reading.

I invite the reader to compare these mountainous physiognomies and spirited gazes with the flabby molehills that grow on the necks of modern authors and literary agents.

And here are some of the most celebrated writers of our time…

This is why, starting with Martin Heidegger, so much modern philosophy, from the largely vacuous (Michael Serres) to the often fascinating (Byung-Chul Han) concerns itself with etymological enquiries into words, and why such authors, notwithstanding their insights, tend to be so passionless and vague. Han, for example, is a darling of the modern democratic intellectual not despite the fact that he says so little about the actual cause of the malaise he dissects, but because of it.