Second part of a four part series. Part one is here, part three is here and part four is here.

The Spread of Plastickese

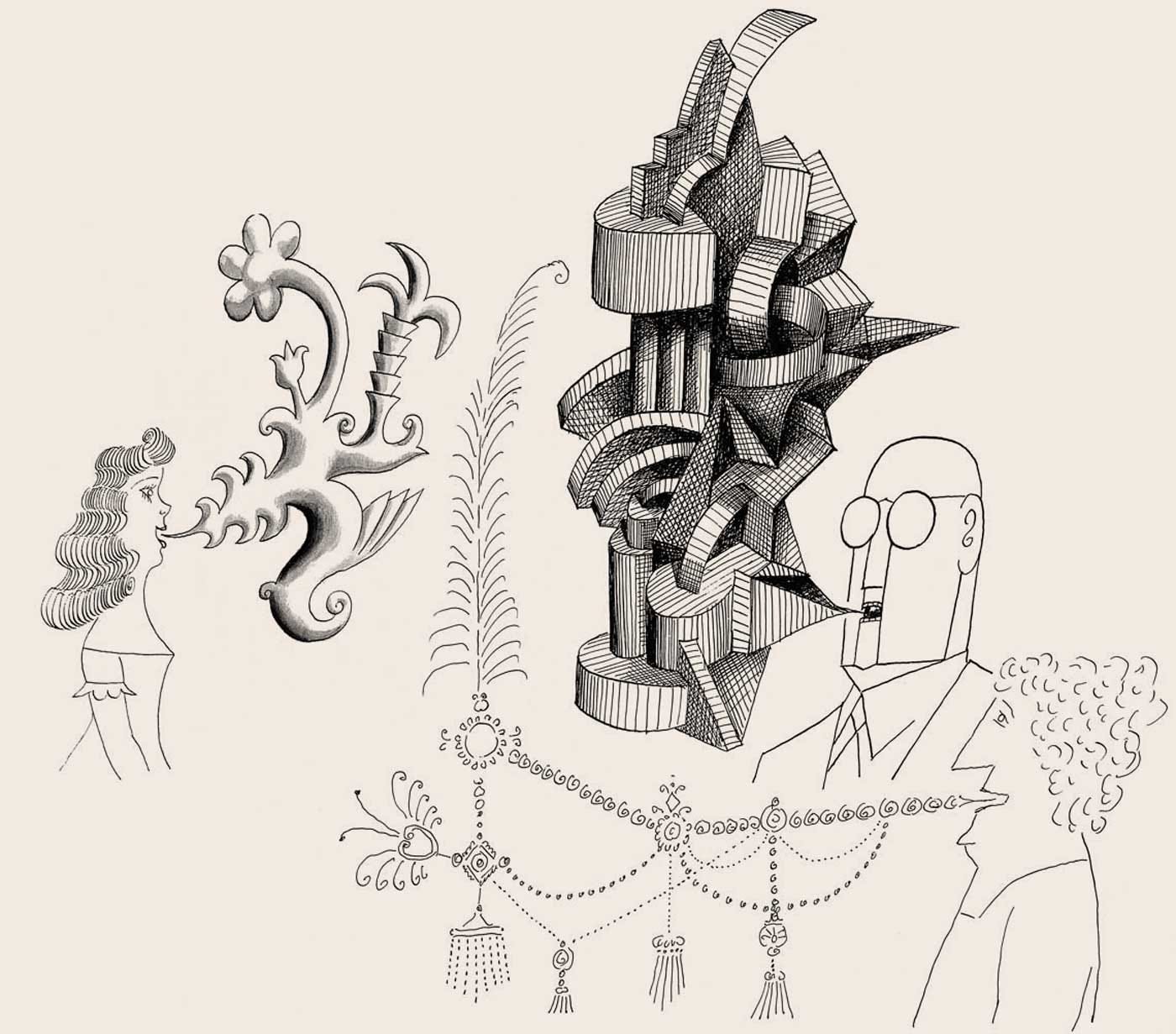

In the wasteland of our speech all kinds of lived experience are swallowed up by generic terms, or ‘plastic words’,1 which are to speech what processed food is to nutrition; technologically manufactured replicas of meaning. Examples include; ‘model’, ‘progress’, ‘process’, ‘necessity’, ‘communication’, ‘interface’, ‘crisis’, ‘case’, ‘care’, ‘development’, ‘energy’, ‘trend’, ‘sexuality’, ‘tension’, ‘partner’, ‘exchange’, ‘formation’, ‘information’, ‘substance’, ‘measures’, ‘identity’, ‘problem’, ‘health’, ‘storage’, ‘release’, ‘factor’, ‘resource’, ‘value’, ‘relationship’ and ‘evolution’. You might have found, reading such a list, a chill pass down your spine. These images might produce a similar reaction, for much the same reason;

Plastic words first appear in, or are appropriated by, institutions, they then gradually spread into2 ordinary speech, where they swallow vernacular alternatives (further degrading ordinary speech), preclude specificity (anything can be a ‘factor’ or a ‘resource’, or be in need of ‘care’ or ‘development’), dispense with value (or with any kind of quality) and smear distinctions into a glib, semantic paste that a distracted listener can blandly nod along to without ever having to ask what all this actually refers to.3 For plastic words, such as they are used today, do not actually refer to anything real, specific or embodied. They may do, or may have once done so, but after passing through the modern system, they are stripped of context and consciousness and become abstract, toneless and, crucially, modular, or interchangeable. Meaningless. ‘Information is communication. Communication is exchange. Exchange is a relationship. Relationship is a process. Process is development. Development is a basic need. Basic needs are resources. Resources are a problem. Problems require care. Care is communication. Communication is information.’4 And so on, ad infinitum, ad nauseum, ad mortem.

A modern speaker of Plastickese might talk about his ‘sexuality’ or his ‘relationships’ — ideas which can, in their nebulousness, engulf one’s entire life (cannibalising, as they go, tenderness, affection, togetherness, friendship, passion, warmth, intimacy, dignity and so on) — or about ‘communication’ — which can take in everything that human beings ever do (while robbing the conversation, the glance, the gesture and the tone of their subtle content) — or about the ‘release’ of ‘stress’ — a low-grade ‘pain rating’ with no real properties (unlike doubt, disgust, resentment, abasement and so on, which all get sucked in to single, pseudo-scientific concepts of ‘tension’ or ‘anxiety’) — or about ‘development’ — which crushes history, personal struggle, human agency and the specifics of our actual lives under a mechanical ‘process’ or ‘progress’ (which, like democracy, rather conveniently absolves experts who operate the machine of responsibility; ‘Guilty? Not I, but progress.’).

None of these concepts can be experienced directly, as a quality, in a natural, human life; which is why nobody really understands them — only technical experts, to whom, once we have learnt to speak and think of ourselves as machines or machine ‘processes’, we are happy to give our lives, lives which we then come to understand as components, or ‘factors’ within a larger machine. This enables experts to gain power over language, and therefore over our minds, without having to overtly propagandise — in fact, without having to say anything at all. Language, insofar as it speaks of matters of real importance, belongs to management, so, as soon as we speak or think about such matters, we are their vassals. The power the specialist appropriates adds further to his esteem, and to the attractive pull of Plastickese, further degrading the poetry of everyday speech, until we are reduced to passive, mute confusion, mouthing technical platitudes without any real understanding of what we are saying.

The spread of Plastickese, and its penetration into ordinary speech, the sense that there is a technically correct way to talk about matters of importance, began with the rise of the professional institution and the official language it used to subjugate meaning, a kind of spiritual cancer already well underway by the time Nietzsche recognised it. ‘Everywhere,’ he wrote, ‘language has fallen ill, and the oppression of this dreadful sickness weighs on all of human development… Man is no longer recognizable in language. He can no longer give a true representation of himself’ because he is possessed by a ‘madness of general concepts.’ As a consequence of their inability to make themselves intelligible, what people create together corresponds not to their intuition of their troubles or to consciousness of their love, ‘but to the hollowness of these tyrannical words and concepts,’5 which have infiltrated ordinary speech from institutional sources so far divorced from ordinary life they may as well be alien spacecraft.

Plastic words grow and proliferate in technocratic systems which demand abstract, modular, interchangeable concepts, just as these same systems demand abstract, modular, interchangeable people; fragmented, fateless nodes, connected to other such points into a mathematical structure which, in its totality, mimics context and consciousness, while having nothing to do with either. As man submits to management, and its vocabulary, he becomes disfigured, like the words he uses, into the plastic mask of language he is forced to wear; he becomes another interchangeable bit which words like ‘capacity’ and ‘faculty’ and ‘resource’ and ‘contact’ and ‘aggression’ can grasp and manipulate, in the expert lab, without having to get dirty in the mud of day-to-day particularity.

Nominalisations are particularly common in the lexicon of plastickese, active verbs and modifying adjectives which express concrete meaning, now transformed, partly from an impatient need for concision and partly to excise the essential truth of an utterance, into passive nouns, which refer, in their excessive generality, to everything and nothing. Compare ‘I value speaking the truth and loving my fellow man’ to ‘My values are truth and love’. The former establishes a fluid link between subject and object and takes responsibility for that link. It then invites you to engage with me, as a living creature which actively does, thinks, feels and senses; the basis for a meaningful conversation between two people. ‘My values are truth and love’ by contrast, removes the subject, me, from the utterance, along with an active object, and presents instead a mental image of a static idea, which effaces responsibility and, as it is hard to talk with an absent person, paralysis engagement.

Other examples of paralysing nominilisations include; ‘development’, ‘progress’, ‘freedom’, ‘desire’, ‘masculinity’, ‘happiness’, ‘democracy’, ‘modernity’, ‘life’, ‘sex’, and ‘labour’. What do these words really mean to us? Who knows!? They do not provoke reflection or meaningful engagement, they hypnotise us into an opinion, one which, in lieu of content requires emphasis. ‘I am against modernity!’ ‘Masculinity is in crisis!’ ‘Pro life!’ ‘Pro freedom!’ The nominalisation lands in the mind, throws up an emotion, a few facts, and a few standard visual associations, which are then roped together with a decisive like or dislike, agreement or disagreement. This is then used to signal one’s membership of a group of people to whom one has surrendered one’s moral autonomy; ‘the people’ perhaps, or ‘the party’, or ‘the church’, or ‘people of colour’, or ‘the best and brightest’ or, more often than not, one’s social media cluster — it doesn’t really matter. Just not me, not I — for I, as a consciously responsible individual do not exist, only my identity and the feelings that sustain it.

One has the feeling of being blindfolded on a space-station,

trying to feed oneself peas with pair of chopsticks.

There is no way to question this identity. Present a reasoned argument to an identity masquerading as a human being, one that demolishes a view they hold, or that even just sensibly questions it, and they are likely to say, at best, ‘yes, yes, but I feel differently’ or they’ll smile and nod and think, ‘well, that’s your opinion, which is just as valid as mine’. More troublingly, what you say seems offensive, arrogant, threatening, offensive, violent, and as seeming is all there really is to life, as the word is as real as the thing it refers to, Badspeech becomes a literal hazard, a threat to life and limb, essentially no different to an explosive device; something which a civilised society simply cannot permit ordinary people to handle.

Actually all nouns, all things, both subjects and objects, are nominalisations, and, as such, illusions. A biscuit is not really a thing, a sliced off bit which exists only now, but a perpetual happening, a verb, biscuiting, which, in its timeless completeness stretches back and forth, from the circumstances of its making to that of its undoing. The dynamic living quality to what appear as dead, static things to the spatial mind is partly what gives these things their enigmatic quality, at least to those sensitive enough to reach through their minds, to the thing in itself. It also explains why, as P.D. Ouspensky noted,6 a beam of wood from a church roof and one from a gallows are radically different objects. To the slicing machine-mind of modernity such an idea is absurd, abstract, mystical, mere poetry. To I, who consciously experiences the beam, and the biscuit, it is the self-evident truth.

Turning experience into nouns, split off from the whole flow of meaning, makes them baffling in their abstractness, a bafflement which finds itself recorded in the annals of Western philosophy. Ludwig Wittgenstein pointed out, over and over again, that there is ultimately no such thing as the kind of ‘meaning’, ‘knowledge’, ‘morality’, ‘goodness’, ‘truth’ and ‘consciousness’ that philosophers and scientists search for.7 There is only life, activity and experience. When we use words we do so in situations that give those words meaning, not in order to get a series of rule-bound definitions from my mind into yours, as if the inner life of the other could be ‘sucked out through a straw’.

We shouldn’t be surprised that modern philosophers spend their lives sucking at meaning through their tiny mental straws. They are just doing what any other priest or technician is paid to do, take ideas out of context in order to take possession of them. Economists do the same with land and labour. Academics rarely see a need for contextual thinking, for viewing an utterance in the milieu or even the passage in which it is made, because to do so would entail paying attention to a context that they are employed to ignore. The tunnel-vision of journalists is even narrower; one only has to open a newspaper to find a concept picked out from times past as one would a single note from a symphony, which, we are then told, makes no sense, or is boring, or, hark, is the siren call of the enemy.

Context-free ideas are common in our world because living eternity, the flowing quality of things, must necessarily be absent from the system which Neospeak encodes and justifies. Eternity is unthinkable — it cannot literally be imagined — and it is imminent — not time going on forever into the future, but time ceasing, now. It is therefore unmanageable. It cannot be owned, bought, sold, withheld or wanted. There is nothing useful about it, nothing reassuring and, perhaps most upsetting of all to guardians of meaning, it is available everywhere to everyone. This is why it must be denied, rejected, refused, banned, abused and all avenues towards it bricked up; not consciously, because consciousness is, in its timelessness, the very threat that assails the management-minded. It is simply ‘obvious’ that one must prevent people from overcoming themselves; by consciously facing pain and death, by discovering themselves through their work, by experiencing the vivid, unmediated beauty of the wild and by freely loving each other. Meaning must instead be dispensed; through the institution, and through the screen. For your own good, of course.

Similarly, in a nominal world of segmented things, ‘God’ must be absent, insofar as the word refers to eternity. The idea of an abstract and decidedly temporal creator-thing sitting up on His heavenly throne, causing things to happen — the false God, or Demiurge, of the Hebrews, Christians and Muslims — served its coercive purpose for pre-moderns, as it did for early scientists promulgating the machine metaphor,8 as it still does for the medieval-minded among us today, but that concept is just not useful any more. Thus, in place of the Demiurge, modernity has substituted ‘communism’, ‘history’, ‘progress’, ‘democracy’ and whatnot, abstract forces with the same totalising power as God, only without His arbitrary laws and outmoded codes. As pre-modern man was the servant of the Demiurge, or realisation of His will, so modern man is a localised manifestation of ‘history’, or ‘communism’, or ‘science’, ever battling onwards, for the cause, to realise a secular ‘heaven’ on Earth, a world of things ruled over by the One Great Thing we must sacrifice our freedom, our real freedom, to.

All this simplifies our moral lives considerably. When the specific, unique, non-duplicable consciousness of the individual is subsumed under categories — identities such as the capitalist, the bourgeois, the leftist, the black, the white, the fascist, the homosexual, the Muslim — and when the distinctions that the individual requires to navigate his or her moral life are melted into the ethical puree of postmodern relativism, we find that instead of right and wrong, fair and unfair, beautiful and ugly — principles that require sacrifice, love, empathy and pain to realise — we merely have to match up whatever is happening to pre-provided nominalised templates, such as ‘equality’, ‘civility’, ‘social justice’, ‘diversity’, ‘patriotism’ or whatever else is deemed to benefit favoured identities. These concepts efface individual judgement, what I, in my heart, know to be good and right, replacing it with a nexus of totems and taboos which I simply match my experience against, as I would urine against a colour chart, not listening, but listening out for examples of Goodthink and Badthink to determine the moral status of the speaker or writer in question.

Plastic language, like all language, has its standard varieties, spoken by technocrats, business leaders, social workers and the like, but it also has its dialects; specialised technical jargons, spoken by subgroups within the mechanical-institutional system. These include Corporatese, Medicalise, Legalese, Academese and Criticalese, all of which blend to each other, but which serve distinct sub-purposes within the wider non-language that the system uses communicates with itself.

Criticalese, for example, the scholastic language of radical critique used in universities, monopolises serious criticism of the wider system, thus making genuine criticism impossible. It comprises words such as ‘encounter’, ‘dialectic’, ‘interrogate,’ ‘gaze’, ‘appeal’, ‘concern’, ‘contingent’, ‘paradigm’, ‘identity’, ‘context’, ‘contextualise’, ‘challenge’, ‘text’, ‘discourse’, ‘possibility’, ‘reveal’, ‘denote’, ‘performative’, ‘perverse’, ‘inform’, ‘transgress’, ‘negate’, ‘mediate’, ‘situate’, ‘terrain’ and ‘status’. These terms, favoured by theorists in the social sciences, but common across the humanities, are not used to further understanding, but to stifle it. Like all plastic language, criticalese deprives us of what it pretends to offer; meaning. It strips language of a specific, recognisable context, it devalues ordinary speech and, like all modular terms, it drains metaphor of concrete reference. Ideas in criticalese occasionally touch shared experience, but they are most comfortable floating in the air, unrelated to anything but themselves. One has the feeling, reading academic books on sociology, philosophy and politics, of being blindfolded on a space-station, trying to feed oneself peas with pair of chopsticks. One grasps a little pellet of meaning before, with a sigh, getting to grips with the next sentence which yields not even air, but its absence.

Take the concept, much favoured by speakers of Academese, ‘the body’. This is not a body which actually exists, the gendered experience of flesh and blood which I am one with. The academic body is a statistical object, an abstract symbol or an ideological construct; knowable, graspable by the mind, and yet, severed from nature, history, culture and the context, perfectly malleable, capable of being shaped by the whim of whatever intellect possesses it. The sovereign whim of that which speaks of ‘the body’ in this way — the hyper-abstract postmodern ego — occupies the place where consciousness once was, and must be protected from the ‘objectifying gaze’ of those who might deprive it of its ‘autonomy’, meaning its right to be a five-sexed dinosaur, or an unsexed embryo, or a gay army general, or whatever else the postmodern self pleases. Real bodies are sexed and gendered, the male distinct from the female, a difference which guarantees both the miracle and mystery of their union. The symbolic ‘body’ of criticalese, in contrast, makes much of ‘the male gaze’ doing all kinds of violence to ‘the female body’, but this latter body is, unlike an actual woman’s body, both literally knowable, and yet as substanceless as a dream, exposed and exposable, yet without position on earth. Any woman who really is a body, who loves being incarnated, who is happy to be poor and stupid before the wealth and intelligence of her senses, is not merely confused by the academic body, but disembodied by it. And that’s the point.

Bodiless Academese as it is spoken and written today can be traced back as far as Immanuel ‘brain-in-a-jar’ Kant, but Kant occasionally made sense and was trying, incompetently, to say something stupendously important. It is to Hegel and his followers we must turn for the source of the superficially profound, but actually weightless, language of the institutionalised mind. Hegel learnt from Kant that in order to conceal one’s confusion, or one’s heartlessness, or one’s essential vapidity, one must throw sand into the reader’s eyes, a lesson he passed on to his progeny; Marx, Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Lacan and a hundred thousand PhD students of critical race theory, queer theory and political theory. Not that anybody reads these people, not even their fellow academics, although this is less because they make no sense9 and more because fewer and fewer people read.

For the literate, written word is also dead. We can talk of an art of writing, just as we can of image-making, which, in place — rooted, as it were, in the soil of speech — permits reverie and the flourishing of culture, but this is not what we are faced with today. Out of place, allowed to spread beyond its natural limits, literacy dominates culture, which, like people who dominate culture, cuts it off from life and makes it sick. When it is in a position of authority over speech, literacy fosters a widespread illusion that one must go through the book to reach beyond oneself, out into culture, or up into the heavens. This suppresses and devalues the spoken word, which then becomes unofficial, non-pedagogic, suspicious. Literacy is thus cut off from meaning, from direct, spontaneous speech, the mysterious spring from which the written word draws its waters. Cement this source over with a hyper-literate, hyper-educated culture of book knowledge and that knowledge — the art of literature — dries up, becomes dead of metaphor, tone and nuance.

Literacy, it goes without saying, has its place. Just as thought, subordinated to the thinker, is a good servant, so the written word, in service to the spoken word, both serves and is served by it. Our relationship — between you, the reader, and me, the writer — is unnatural, mediated and one-sided, and we must treat the technology which forms this relationship with extreme caution and respect; but to the degree that I am, first of all, conscious, and able to speak naturally from that consciousness and, second of all, have mastered my craft and can do justice to my speech in written form, I can say something, and you can hear it, and a fruitful conversation can then occur, albeit one that flows inward and outward diffusely, through our pores, so to speak, to and from our wider culture. You can’t really respond to me, at least as you are reading, but to the degree that you follow what I am saying, it becomes part of your mind, as food becomes part of your body, and then part of your conversation with the world.

This is particularly important today, encased as we are in a highly developed system, which has all but destroyed human culture. If we couldn’t communicate through the written word, we would be in a similar position to someone unable to eat any factory-farmed food; weak and starving, or driven to lead an impossibly inconvenient10 life. And this, in effect, is the situation we face in a culture, such as ours, which is eroding literacy, a culture which has imposed attention-corroding screens between its people, which has turned its back on its own cultural tradition, both written and spoken, which either does not or cannot teach itself to read and write in any but the most perfunctory sense. The people of such an anti-culture, who have no access, in any meaningful sense, to either the spoken or the written word, who can only read self-contained captions, comments and chat, who, even when they can read books, do so to consume information or to be reassured11; such people are starved of sense, and their culture becomes senseless.

Part 3, The Humiliation of Speech, is here. Part 1, the Death of the Word, is here, and Part 4, the Final Word, is here.

Uwe Poerksen, Plastic Words, The Tyranny of Modular Language.

Or back into; again, many have their origins in ordinary speech where they still can be used meaningfully.

Again, think of ultra-processed food, which slips down without effort, but has no nutritional content and, as part of a monocultural farming system, destroys the possibility of real food.

Uwe Poerksen, Plastic Words, The Tyranny of Modular Language.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations.

P.D.Ouspensky, Tertium Organum.

When philosophers use a word—‘knowledge’, ‘being’, ‘object’, ‘I’, ‘proposition’, ‘name’,—and try to grasp the essence of the thing, one must always ask oneself; is the word ever actually used in this way in the language-game which is its original home? What we do is to bring words back from their metaphysical to their everyday use.

Philosophical Investigations, Ludwig Wittgenstein.

And making use of the dire Jewish metaphor of creation, which gave Adam controlling dominion over the Earth

I should point out that these writers are certainly not charlatans. Their work, to varying degrees, contains important truths. Not as much as is commonly believed, but I’m speaking here of style, and of ultimate truth.

Or wealth-sheltered.

Take a look at what bookshops sell now to see the kind of things modern people feel they need to read. See part two of The Literary Wasteland.