How to Be Unlikeable

A Guide for Nice People

One can always be kind to people about whom one cares nothing.

Oscar Wilde

Whether you are liked has no bearing on who you are, how moral you are or on how genuinely warm, generous or loving you are. Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini were liked by millions of people, as were John F. Kennedy, Tony Blair, Barack Obama and other likeable mass murderers. There have been plenty of likeable serial killers, such as Charles Shobhraj, Richard Ramirez and Ted Bundy,1 along with a vast nameless number of well-liked child abusers, rapists and wife-beaters.

Beethoven, on the other hand, was disliked by many who knew him, Socrates doesn’t seem to have been very well liked, Voltaire certainly wasn’t, Van Gogh had a big heart but annoyed everyone he met, as did D.H. Lawrence, as did Rameau.2 Rembrandt was a pain in the neck, as was Michaelangelo, as were many other great writers and artists. Genuine spiritual teachers are very often no different. I don’t think many people would have accused U.G.Krishnamurti or Barry Long of being nice and likeable. Gurdjieff delighted in making people’s lives difficult. Jesus of Nazareth was hated, and, who knows, but it’s hard to believe that the Buddha and Chaung Tzu made friends everywhere they went.

The reason why so many people whom we honour are so unlikeable is very simple; there is no good reason for them to be likeable. Actors have to be likeable, as do politicians, professionals, popular television presenters and other prostitutes; but writers, teachers and artists? What can they gain from being liked? Fame? Popularity? Money? Awards? Status? Is that what it’s all about? Is that why they work? Is that what you want from them? Someone who knows how to be popular, how to be liked?

People who speak the truth are unlikeable because the truth is unlikeable. The truth is, at least to the self, annoying, disturbing, hurtful and, in extremis, absolutely horrifying. It is disorienting to read or hear of it, painful, indeed pain is how you know it is the truth. It can be, at least to the self, positively agonising to experience reality, so one can hardly be expected to find reading about it reassuring. If it is, you can be certain that you are not actually encountering anything of real value, but a sop, something said in order to gain approval, to reassure you and to make you feel good.

This is why the greatest artists and teachers—particularly writers and speakers—have a tendency to be unlikeable, unpopular, ignored, ridiculed and hated. Not always of course; plenty were congenial and affable types—in a sense, being likeable is a little like being tall, sometimes useful, but irrelevant to integrity; although even chirpy and agreeable writers and artists frustrate their readers and upset people who can further their careers. Those who speak the truth have a tendency to burn their bridges with editors, agents, influencers and the public. They may complain about their obscurity and poverty, or they may not, but they refuse to compromise with what they know to be the truth.

Does this mean writers worth reading and speakers worth listening to are wantonly abusive, that they humiliate their listeners, that they enjoy conflict and hatred and contention? Only a child enjoys these things. Does it mean that authenticity means being rude, cantankerous and fault-finding? Not at all; the greatest discourtesy is to be intolerant of discourtesy, the greatest folly to be perpetually judging folly, the greatest vice to see nothing but vice. Does it mean that great minds are necessarily saints? Of course not—we all upset people for no good reason and regret it. What it means is that you cannot say or create anything meaningful if you are worried about treading on other people’s opinions. Such fear, founded on the desire to be liked, is compromise and death. Indulging a reader’s sensibilities is a Judas kiss.

This is why when whores and flatterers die, they are forgotten. Indeed those who write to live, rather than live to write, are often forgotten long before they die, when fashion moves on, or when those they pander to lose influence. It is also why those who refuse to compromise live on, because they are not speaking to the sensibilities of those who buy or print or promote books, to agents and publishers who are not looking for the truth in what they read but for someone to tell them what they and everyone else already agree with.

Hardly anyone reads books or listens to speeches to discover something that is actually new. They tell themselves they do, but what they are really looking for is confirmation of their beliefs and, more profoundly than this—for beliefs are rather shallow things, which people will give up at a push—for confirmation of the feelings that these beliefs are founded on. An author who answers their beliefs or indulges their feelings, who creates a warm glow of reassuring recognition, is likeable, and one who doesn’t, is unlikeable, or difficult, or bitter, or whatever else seems to fit.

‘But, but, but,’ says the professional writer, ‘I can’t upset my readers. I need to pay my bills!’ Maybe you do, but if your bills are more important than the truth, you’re a whore. You journalists don’t actually have to prostitute yourselves to the editorial line—you can leave. You writers don’t actually have to prostitute yourself to what most of your readers feel and believe—you can remain in obscurity. You entertainers also. You can sing on the street if need be. I know, I know, dreadful isn’t it? You’d probably have to get income elsewhere, from a crappy job, for example, where you’d still have to compromise, but at least, when you went home and put your pen to the paper, your integrity would be intact. Isn’t that worth sacrificing your shoddy desire to be liked for?

Apparently not. Such sacrifice is not very popular, which is why, first of all, those who don’t have to make sacrifices easily succeed—those whose conformity and mediocrity are so ingrained it appears to emerge naturally, without apparent compromise. The prize-winning novelist and well-paid columnist don’t need to be told what to write; which is why they do well. If they had to be told they’d already have been ejected by the long filtering process of education and recruitment.

The rarity of sacrifice is also why love, the kernel which sacrifice reveals, is so rare in this likeable world. Because love is not likeable. That’s why we have such radically different words—love and like—to indicate the difference, why, for example, we love some people who annoy the hell out of us, but could never love others, who are totally inoffensive. It’s also why keeping people on your side (customers, colleagues, bosses, sons and daughters), never criticising them, never standing up to their emotions, spoiling them; why this, which so often goes by the name of ‘love’, is really a kind of hatred and cruelty, or at best, unforgivable cowardice.

We want to be liked because we are cowards. It’s not really because we are nice and caring, it’s because we cannot bear rejection, obscurity and loneliness. This is why parents raise likeable demons and why audiences raise likeable mediocrities and why crowds raise likeable monsters. It’s why companies, dependent on custom and good reviews, produce likeable excrement and why, as we suppress all the frustration and rage that a likeable life, policed by smile Nazis, imposes on us, we find ourselves surrounded by such bizarre and frightening violence, which doesn’t exist despite all the wondrous niceness, but because of it.

‘If being unlikeable is the game,’ you might be thinking, ‘everyone is playing a bit too well aren’t they?’ Yes indeed. This is particularly clear to those of us without enough money to keep our fellow man at arm’s length, pressed up against him in his selfish misery and insensitive cruelty. The rich can afford to have a rosy view of people, while those of us who can’t escape them, are all too aware that men, such as they are, have precious little self-control or concern for their fellows. They have no experience of the other from within, which makes them, at best, painfully dull, unaware that they are boring all who come within their ambit, at worst, unempathic monsters, their morality a matter of tactics.

But in any case, these are people in their off hours, when being ‘oneself’—a drunk, a bore, a bastard—is permitted. Mandated, even. It is at work that likeableness is law, where one must please the largest number of people—ideally all of them—or lose votes, sales and ratings. It is at work that one must speak bullshit, serve excrement, or suck cock, with a rosy smile on your face, because that’s what the punter, or the market, likes. It is at work that you must be nice to everyone above you with money, prestige or followers, never upsetting them. Work demands likeableness. Doing a good job is a remote irrelevance.

The religion of the likeable goes by the name of ‘democracy’, which means being likeable to the largest number of people possible, an invisible mass which is, effectively, God. If you want to hold fast to a moral sense which is independent of a wholly group-directed neurosis, you’ll soon find yourself persecuted. If you want to serve food in your restaurant, or show art in your gallery, or make election pledges on your manifesto, and most people don’t like what you’re offering, you can forget it. No matter how good your food, or beautiful your paintings, or ethical your manifesto, if it’s not likeable, fun, optimistic, easily digested and, above all, painless, it will be damned to hell.

As with every other religion, there is no need to be pious in your off hours, but even at home, there are some limits to how sinful you can be. Democratic civilisation, in its most advanced technocratic state, demands the complete disintegration of all borders, the membranes which separate gendered and cultural domains.3 Everyone, no matter what their sex, race or religion, must live together—liking each other—in service to a system which has no need for such archaic ideas as ‘gender’ or ‘culture’. Nobody is allowed to express the slightest unlikeable antipathy towards other groups of people, particularly those with professional power.

The formal system then demands enforced selflessness, which is why, as soon as we clock off we find we need self-absorption and self-assertion, which are the principle attraction of drugs which more securely lock us inside ourselves (alcohol in particular, but also cocaine, heroin and the heavier varieties of cannabis). We are marshalled into an ever-decreasing circle of ourselves, but our hatred does not diminish, rather intensifies, waiting for a moment to erupt.

A similar situation occurs in the personal lives of likeable people, afraid to speak the unlikeable truth to their parents, or to unlikeably restrain their children, or unlikeably reject their partners, all their frustration pushed down and down, pressure building up, until it breaks out in madness, or sickness. There is nobody so terrifyingly violent as a nice guy. If you’re in any doubt about this, try telling the truth to your nice, non-violent friends, or wait to see how all your nice non-violent neighbours behave when society finally breaks down.

Being cruel and spiteful is not the opposite of being likeable, but its consequence. The alternative to being held hostage by the cult of happy is not a world in which everyone goes around abusing each other, any more than a world which allows us to get sick and hurt ourselves is one in which children would wantonly throw themselves into park lakes. As with all forms of insanity, self-indulgent lack of empathy manifests as two apparently opposite, but fundamentally identical forms; in this case being masochistically nice and being sadistically nasty, two fundamentally identical states of being which an extraordinarily large number of people spend their lives see-sawing between, keeping a lid on their frustration and anger until it either collapses in weary misery or erupts in bizarre, inappropriate hatred and rage.

We come to believe that we need to keep ourselves constrained by niceness, and by law, and by power, because as soon as these are relaxed for a hot second, all hell breaks loose, confirming our fears. But that hell is a consequence of being released from confinement. Let go of the civilised, systemic need to keep everyone happy, to pander to their likes and dislikes, to give the punter what he wants, to play to the gallery and to never upset anyone anywhere, particularly the paying, voting public, and we will instantly find ourselves in an unsettling world of debt-settling savagery. Just as a field that is released from the pressures of industrial farming is suddenly overcrowded with weeds, and a workforce freed from economic necessity instantly goes on a spree of hedonistic pleasure-seeking, so a suppressed world that finds itself able to say anything straight away sets about saying terrible, terrible things; but such effects are the consequence of our prior confinement, not of freedom, which sooner or later settles down to an equilibrium, in which discernment prevails; in which love is free to be unlikeable.

CASE STUDY 1: THOSE LIKEABLE LOCKDOWNERS

A good example of likeable behaviour was exhibited during the two-year ‘pandemic’ beginning in February 2020. It was clear in April of 2020 that something extremely fishy was going on, and by summer of the same year it was all but certain that a colossal fiction was being used as a justification to cool down a disastrously overheating economy and expand the reach and power of the technocratic system. Anyone who cared to look at the reality of the situation knew that PCR tests were being used to inflate the severity of a flu-like illness which was having zero meaningful effect on all-cause mortality. During this time, most people, particularly the professional class, but also the submissive lower classes, accepted the reality of the situation presented through their screens over that which their eyes were presenting to them in their ordinary lives, a reality in which bored doctors and nurses danced away their hours through lack of patients and hardly anyone knew hardly anyone under the age of sixty, including any celebrities, who was dying of the deadly virus.

And what was behind the lockdowns, and then the vaccines? It was the professional class, being nice to us; all those nice doctors and scientists and well-meaning television presenters. Even a few politicians genuinely believed they were being nice and kind. This solicitude is founded on an unconscious attachment to the system and to those who own and manage it, which manifests as a reflexive worship of what the system calls ‘life’, an objective and measurable thing which must be, first of all, represented and measured, and then technically managed in order to maintain optimum levels. This activity, called ‘saving lives’, justifies, on the one hand, more control, more surveillance and more technology (and, handily, more wealth, power and security) and, on the other, less ‘risk’, less nature and less freedom, all of which, like the people who value these things, are just not very nice.

A minute group of not very nice people opposed lockdowns, publicly rejected the ‘pandemic’ narrative, and pointed out, at the time, that it was lie, but most people remained silent, either through brainwashed stupidity or, in the case of those who knew that the official story was a lie, through rank cowardice. This latter group, comprising mainly the professional class and leftists, did not speak out because they were afraid that they would lose their platform, lose their audience or lose their fame. Even when governments were coercing their populations to inject themselves with dangerous experimental gene-therapy (which they were calling ‘vaccines’), people with a duty to sound the alarm were raising, at best, oblique and guarded objections. Usually none at all. It was only when it became safe to object that the essays and opinion pieces and podcasts and interviews started appearing questioning the vaccine (rarely the ‘pandemic’ itself or the lockdowns). It became safe to object because the crime had already been committed. It is always safe to allow people to protest and complain after the deed has been done. It’s when it’s actually happening that we need voices raised. But where were they? They were at home, being likeable.4

CASE STUDY 2: LIKEABLE SNOWFLAKES

The children of famous men are without talent and intelligence, the children of successful civilisations are feeble, gelded creatures and the children of wealthy parents are spoilt, brattish, self-absorbed mediocrities. Just as an excess of physical comfort produces weak bodies, so an excess of mental comfort produces weak minds; and what is comfort if it isn’t nice? Our civilisation is, every step we take through it, nice to us. It doesn’t offend us, it doesn’t expose us to unpleasantly difficult or different ideas, it isn’t dangerous, nothing unexpected happens and everything and everyone behave predictably; nowhere more so than in the medium through which our civilisation takes place, the virtual world, which automatically removes every sharp edge, hard surface and chilly wind from our painless virtual experience.

This isn’t to say that horrible things don’t happen in our world; they do, continually, but rarely by design, and rarely to us. The perfect civilisation is harmless, easy, warm and cosy. If someone dies, or if they go postal, of if there’s a war, it’s an inexplicable ‘tragedy’, certainly not a consequence of this nice, nice world. Similarly, a world of preening, puppy-faced, genderless men, the dissolution of limits and borders and a generation raised to fear the slightest pain and criticism; all this can’t be the result of our nice cars, nice computers, nice smartphones, nice central heating, nice electric blankets and the fact that we don’t need to do any nasty physical work because nice machines can do it now, or the ever-so nice Chinese. And it can’t be because of our nice leaders and governments, who only want the best for us. If all of this were the case, we might find ourselves questioning the cult of nice, and the idea that the only moral way to respond to the system is by being nice and loving and forgiving and pacifistic. And that won’t do.

Complaints about effete intellectuals can be found from many civilisations that are losing the plot. The reason is that vastly over-extended hierarchies require more and more abstract management, which entails a class of abstract managers who do little unlikeable physical work and have little to do with the unlikeable stuff of life. Our civilisation is not only over-extended it is also increasingly virtual, with hierarchies distributed into the ether and even, to the extent that artificial environments manage us, non-existent, leading to even more discarnate priorities, not just among the management class, but amongst the virtualised drones, the ‘affectionate machine-tickling aphids’5 of the modern screen slave. The result is that everyone is slowly being colonised by a paper-thin simulacrum, wasting away and losing all experience of reality, which rises up before them as a kind of demon, and a very unlikeable one at that.

CASE STUDY 3: NICE GUYS FINISH LAST

Why is Milton’s Satan more interesting than his God? Why is Tolstoy’s Levin less attractive than Vronksy? Why do we care more about Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster and Heathcliff than we do about Jonathan Harker, Victor Frankenstein or the Lintons and Earnshaws? Why are there so few interesting nice guys in literature and so many fascinating rogues; Captain Ahab, Stavrogin, Pechorin, not to mention the fictionalised autobiographical versions of Céline, Miller and Bukowski? Why is it that the greatest goodies — Lord Krishna in the Puranas, Monkey in the Journey to the West, Huckleberry Finn — are strangely amoral agents of chaos and trickery — or are actually punished for being nice — Parzival, David Copperfield, Jude Fawley, Miriam Leivers? Finally, why are Dante’s inferno, Gissing’s New Grub Street, Dostoyevsky’s Siberia and Levi’s Auschwitz — set in filthy or even hideous conditions — so popular?

Nice guys have been wondering something like this for centuries. For some inexplicable reason girls, particularly the soft and loving ones, seem to find conspicuously un-nice fellas to be far more attractive than their nice and lovely male friends.6 At the pathological end of this impulse we find lovely women falling for complete and utter bastards and even murderers. There appears to be, in the best of conditions, and despite what women might say, something rather unappealing about an extremely nice man, something uninteresting, something frustrating or even disgusting; the kind of disgust a coward evokes.

The truth is that artists and gentle women know, as we all do somewhere inside us, that, as Kierkegaard put it, ‘there is more good in the demonic man than in the trivial man.’ This doesn’t mean that the demonic man is moral, obviously not, or worth emulating; it means that there is something in him that the trivial man lacks. Above them both we find the loving man, the great man, who has that something in him too, something unlikeable, something demonic, something good.

CASE STUDY 4: THE UNLIKEABLE TRUTH

The truth, like nature, is no respecter of boundary. Ultimately it transcends thought itself, which is why a concept such as ‘power’ or ‘freedom’ can appear absolutely right in one context and absolutely wrong in another; for, ultimately, the source of all good is the context, the situation, and my conscious experience of it. As soon as I depart from this experience I find concepts no longer fluidly serve me, but become totems and taboos which I must serve.

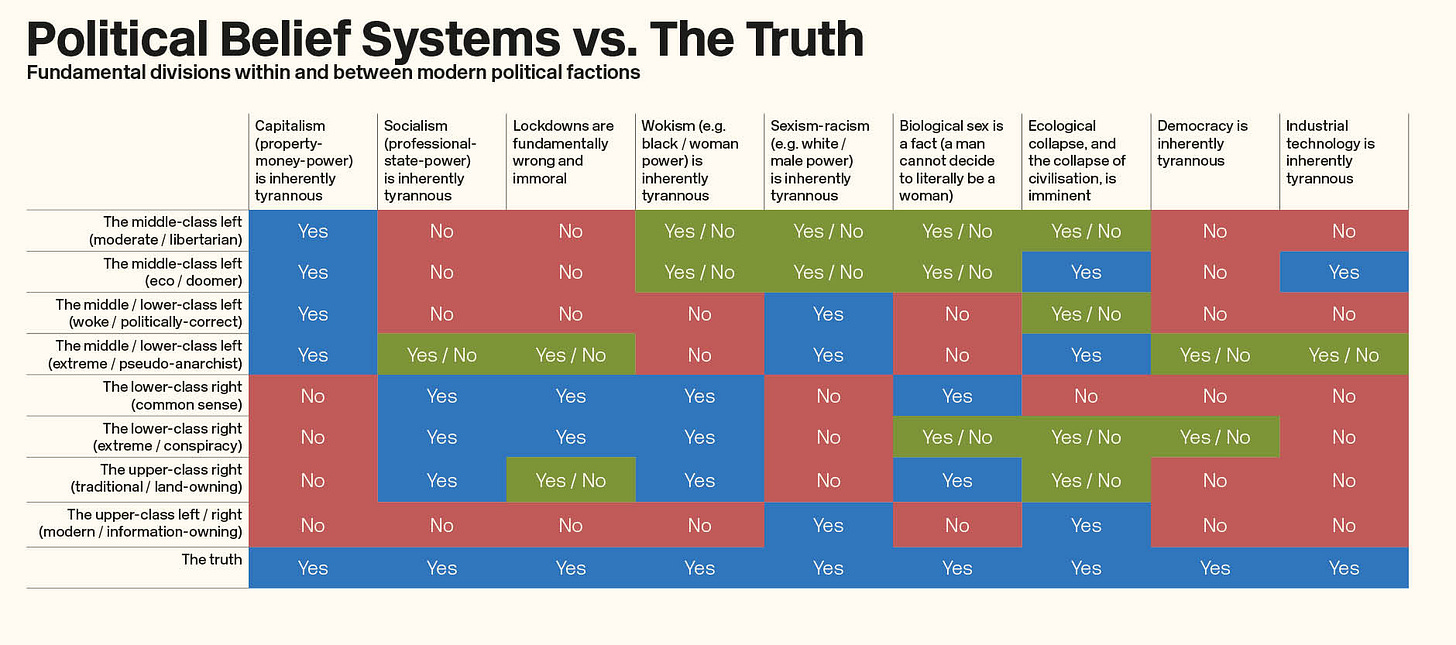

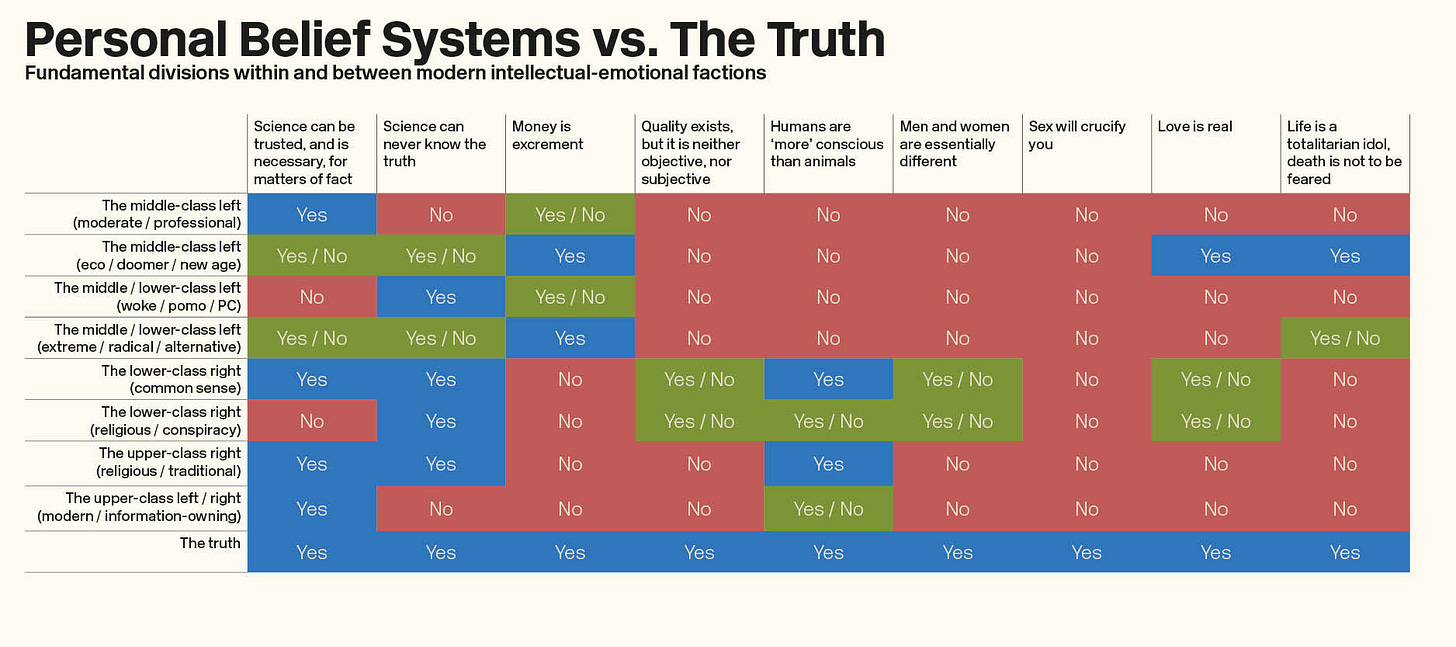

Such totems and taboos are largely a matter of self-interest, which in turn tend to be largely a matter of class-interest. The lower-class have a very different moral outlook than the middle-class, which in turn sees right and wrong in wholly different terms to elites. Sometimes their needs overlap, as often happens in a threesome — when two gang up against one — but mostly these interests remain distinct, manifesting as what we call the ‘right’ and the ‘left’, ideological factions founded on instincts either to preserve the power one enjoys or to get one’s hands on the power which one merely endures.

Those who seek to free themselves of self-interest and class-interest gradually discover a truth which threads its way through partisan ideologies like a seam of gold through rock. Thus, at any one time the truth can appear, to factional thought, either friendly or unfriendly, either marxist or fascist, either good or evil, either likeable or unlikeable. Anyone who speaks the truth, or speaks up for it, one minute appears, to one faction, to be prophet of love, the next an avatar of Satan. A second faction might now be whirling their rattle clackers, but as soon as the subject changes, that crowd will turn murderous. The truth can no more survive a journey through a factionalised society, or a factionalised mind, than an honest man can survive a lifetime at work.

All this explains why practically nobody with any kind of power or platform, either on the left or the right, ever critically ventures into topics outside of their specialist subjects, into areas their employers or their public may be challenged by. They’ll build up a nice little career calling out the equality-fascism of woke liberals, say, or the hypocrisy of corporate journalists, or writing about the philosophy of mind; while privately nursing heresy in their breasts on subjects which don’t fit neatly into their profitable niche. An author or speaker who is honest and truthful about a wide range of subjects is guaranteed to get nowhere.

Ed Kemper, Jeffrey Dahmer and John Wayne Gacy were also described as ‘ordinary’, ‘normal’ and ‘likeable’.

Bach also appears to have been disliked by many who had to deal with him.

Although formally atomised elements are kept distinct and isolated.

The left are particularly susceptible to the cult of niceness because they tend to be institutionalised creatures who engage with their fellows through abstract and indirect channels. They are trained to internalise their frustrations, using spiritual practices, stripped of their revolutionary objectivity (not to mention painful self-enquiry), in order to do so, which explains the enormous popularity of meditation, ‘heart-work’, Christian pacifism and similar soporifics among the management class. In addition, ‘tolerance’ is one of the key totems of the left (the right are more likely to be openly cruel because ‘freedom’ is one of theirs). Being openly un-nice sabotages the system which the left are tasked to manage, a system which demands a blandly kind, smoothly running social machine that, in turn, demands uninhibited movement of human capital and the ‘right’ for all people, of whatever age, race, sex or body-shape to be able to alienate themselves and subjugate others in the disciplinary practice known as ‘work’. Owners are a little less interested in being nice because they have less to gain from it. They’ve always been very keen on everyone else being nice however, and they’re no strangers to fear of rejection, dependency on external validation and on covert deals struck with the victims of their niceness; I’ll be nice to you and you must be so to me, if you criticise me, well then you’re a scoundrel.

Samuel Butler, Erewhon.

Hard women tend to go looking for soft men, someone they can push around, or they avoid men altogether and stick, safely and nicely, to women.