Imagine a world in which all culture was produced by artificial intelligence. Not just all literature, music and art, but also history and politics, and even your entire social life. In this world, all slebs, all cultural figures and everyone you interact with are all artificially generated. The horror of such a dystopia, more terrible than that envisaged by Orwell, Huxley, Kafka and Philip K. Dick, is not that it will be literally realised, which is impossible, but that,1 in a sense, we are already there. AI is just putting the finishing touches on a process that stretches back decades, centuries, even millennia. We are, in a sense, already androids consuming an artificially manufactured spectacle, and have been for a long time.

But in what sense? How can it be said that we have always been the castle? For it cannot be denied that AI unculture is introducing a new kind of disorienting horror into our daily lives, a new kind of madness. Until now, we have been consuming content on the internet produced by insane people (and then asking ourselves, after feeding day and night on their misery, fear and mindjunk, why we don’t feel right in the head), but from now on we’ll be gorging on a pure, uncut form of madness, a hyperrefined unreality that will strike at a far deeper layer of conscious experience, with unimaginably dire psychological consequences. So in what sense has nothing changed? What are we losing and what have we lost?

The Expressive Egg Cultural Turing Test

By way of introduction and guide to what AI is depriving us of — and what we had long been without — I’ve put together a ‘Cultural Turing Test’, a ‘reality vs AI’ questionnaire. There are lot of these kinds of test around now, but I’ll be using this one to make observations which are different to and, I venture to suggest, more profound than those commonly available.

Below are twenty-four works of art, music and poetry divided into twelve pairs. Take a read, look and listen and ask yourself in each case first, which one you prefer and then, which one you think is an authentic human creation (which will probably be the same answer, but not necessarily).2

(If you are inspired to show this test to other people, your students perhaps, or friends or colleagues, please do the same — first of all, before you tell them this is an AI-Turing test, ask them which they prefer, and then go back to the start and ask them to tell you which ones are AI. And do let me know the results).

Question 1 (poetry: Elizabethan drama)

Which of these two lines of dramatic poetry do you prefer? One was written, in iambic pentameter, by a famous sixteenth century playwright, and one by AI.

A fearful eye thou hast: where is that blood

That I have seen inhabit in those cheeks?

So foul a sky clears not without a storm:

Pour down thy weather: how goes all in France?

Enter, my friend—thy presence warms this place;

Come sit, and let thine weariness depart.

The mind, like shadows, flits from thought to thought,

Yet what we seek is but to be at ease.

Question 2 (poetry: Romantic sonnet)

One of these is an extract from an original work of nineteenth-century poetry, in the sonnet form, by a famous Romantic author, the other is AI.

O thou lone spark that burns beneath the wave,

Entombed in oceans where no mortal strays,

What hand unblessed thy lamp eternal gave,

To kindle night in death’s uncharted maze?

No planet sings to thee in silver flight,

No moon doth mark thee in her dreaming round;

Yet still thou keep’st thy vow to ancient light…

Ye hasten to the grave! What seek ye there,

Ye restless thoughts and busy purposes

Of the idle brain, which the world’s livery wear?

O thou quick heart, which pantest to possess

All that pale Expectation feigneth fair!

Thou vainly curious mind, which wouldest guess

Whence thou didst come, and whither thou must go…

Question 3 (poetry: modernism)

Now try these two, in a modernist style, from the early twentieth century.

I ask—what’s this hum?

streets tremble—me, or them?

Shadows flicker—are they

speaking? I wait—

the signal—does it bend?

Electric static—what breaks?

Footsteps scatter, no rhythm,

lost? Or I? Between blinks—life

drifts—somewhere?

Graveyards?

I suppose they are—

Fun.

This fellow down here—

Who

Whom did he love and—

She?—Did she did she have cruel—

Eyes?

Did she oh—those trees !

Why do they hunch their backs and—

Sigh?

Did she—and that wind

Question 4 (poetry: contemporary blank verse)

One more; two modern poems in blank verse…

I can hear little clicks inside my dream.

Night drips its silver tap

down the back.

At 4 A.M. I wake. Thinking

of the man who

left in September.

His name was Law.

You hand me the peach

without looking.

Somewhere, a bird

gets the note wrong

and keeps singing it anyway.

We sit, toast cooling,

the radio low with someone’s idea

of happiness.

Question 5 (art: renaissance realism)

Fine arts now. First try these two renaissance pieces.3 Again, first ask yourself which you prefer, and then which is made by human hand?

Question 6 (art: impressionism)

Which of these do you like most? Which is an acknowledged masterpiece of impressionist painting and which an AI mouse-click?

Question 7 (art: anime)

Two images of anime girls, one involved many movements of a human hand, the other, the click of a finger tip.

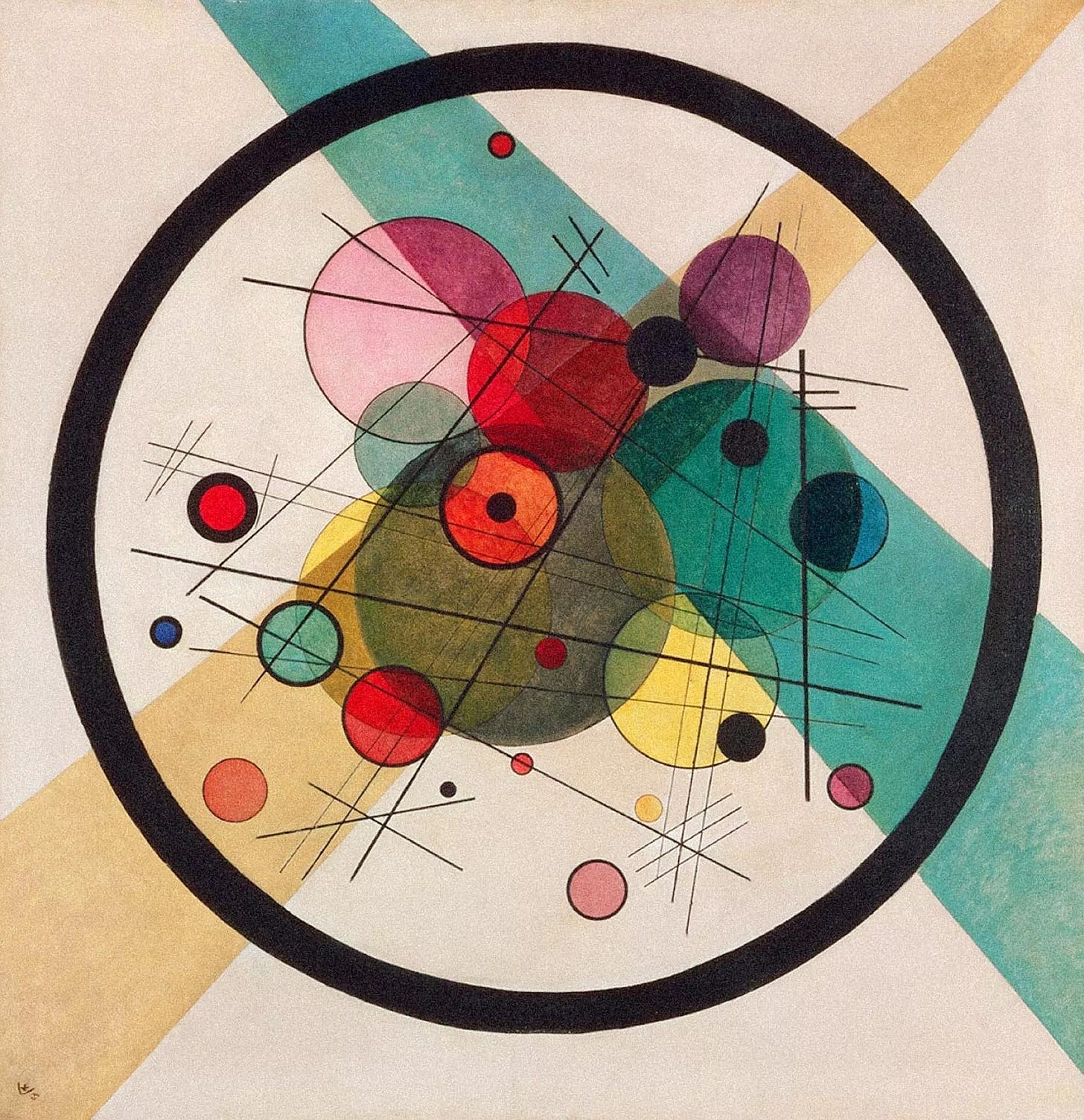

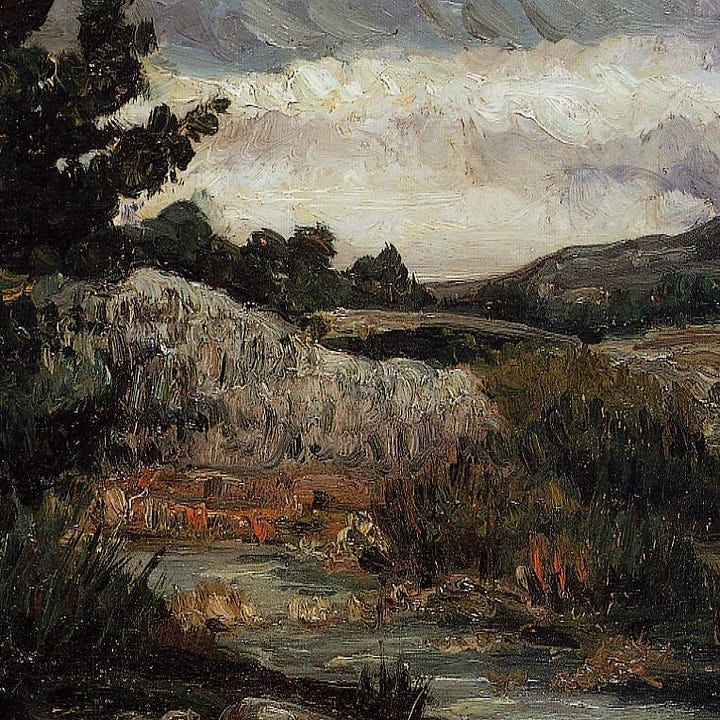

Question 8 (art: abstract impressionism)

And here are a couple of ‘abstract impressionist’ images. Once again, first ask which one you like, then which one was made by a computer. You’ll note here that the one on the left has texture, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s by a human hand. Computers can mimic blobs of paint on a virtual canvas.

Question 9 (music: romantic piano)

Music now. Which of these pieces of impressionist piano music do you prefer, and which one do you think was composed and performed by a human?

Question 10 (music: Motown soul)

What about these two Motown covers of Beatles songs?

Question 11 (music: modern classical)

What about these two pieces of modern classical music (actually film scores)?

Question 12 (music: contemporary pop)

Finally, which of these pop songs do you like most, and which do you think was produced by an android?

The Answers

Now check your answers. Don’t fret too much about finding the questions hard, or getting a few, or even a lot of them, wrong (yes, wrong). As I’ll explain, in many cases it’s forgivable, but pay particular attention to how you answered questions 1,2,5,6,9,10 (the first two in each set of four) as opposed to 3,4,7,8,11,12.

Question 1 (poetry: Elizabethan drama). The first extract is from Shakespeare’s King John. The second is AI.

Question 2 (poetry: Romantic sonnet). The second poem, Ye Hasten to the Grave, is by Shelley, the first is AI.

Question 3 (poetry: modernism). The second poem, Courtship, is by Alfred Kreymborg (no I’d never heard of him either). The first is AI

Question 4 (poetry: contemporary blank verse). The first poem, The Glass Essay is by one Anne Carson (again, unknown to me before I did this). The second is AI.

Question 5 (art: renaissance realism). The second image, St. Catherine of Alexandria is by Raphael, the second is AI.

Question 6 (art: impressionism). The first image, Mont Sainte Victoire is by Cézanne, the second AI.

Question 7 (art: anime). I’m not sure who the artists are here, but the first one is genuine (created on a computer), the second one AI.

Question 8 (art: contemporary abstract impressionism). The first image, Loop the Loop, is by a modern artist (new to me), Stephen Conroy, the second is AI.

Question 9 (music: romantic classical). The first piece Un Barque sur l’Océan is by Ravel, the second is AI.

Question 10 (music: Motown soul). The second piece, Michelle, is by The Four Tops (covering the Beatles), the second was an AI version of The Word. Both original Beatles songs were on the same album, Rubber Soul.

Question 11 (music: modern classical). The second piece was by Thomas Newman (the soundtrack to The Shawshank Rebellion). The first piece was AI.

Question 12 (music: contemporary pop). The first piece was Taylor Swift’s Stay, Stay, Stay, the second was also written by a machine.

You’ve Got a Good Excuse

Did you do badly? Don’t worry. A few mitigating caveats need to be dealt with before we move on. Firstly, all this is going on through the screen. Listen to a great actor recite Shelley, or go and see Raphael’s glorious St. Catherine of Alexandria at the National gallery, or (imagine going to) listen to The Four Tops at an intimate live venue, and then compare those experiences with their AI equivalents. You’d be a lot more confident about which one was real. Even to take a closer look makes the difference between human and AI much clearer…

…because AI cannot perfectly replicate meaningful details, at least details which cohere with the whole context in which a work of art was created. If you look closely at a great work of art you’ll recognise the truthfulness of the details4 while If you zoom in to an ‘amazing’ AI image, of a temple for example, you’ll see that the details — windows, columns, decorative flourishes — don’t quite ‘make sense’. They are not embedded in human experience — and the cultureworlds that naturally result from such experience.5 This is not just a question of historical literacy, of knowing your Doric columns from your Corinthian (or having a technical understanding of how light works), something just feels off…

Talking of historical literacy, a second caveat, before we look at why so many people cannot tell real from fake, is that, when it comes to the art of the past, most people, particularly those outside of Western culture, are culturally illiterate. They do not work within a tradition — nothing is meaningful is ‘handed down’ to them in their work — nor, in order to overcome this crippling psycho-social handicap, do they spend any serious time exploring their roots.6 They do not study art, craft, literature, painting or architecture, and so, when asked to tell real from fake, genius from dross, they cannot discriminate.7

This is tragic, but in one sense it is to be expected and excused. Just as it is unreasonable to expect everyone to be able to tell the difference between a diamond and moissanite, or between the song of a garden warbler and a blackcap, or between a Ming- and Qing-dynasty vase, so it is unfair to expect them to sense out the fine nuances within a classical music performance that mark it as real. This is why the Shakespeare, Ravel and Raphael questions are, for many people, more difficult than the Shelley, Cézanne and the Motown, because the former are more remote and require study to reach.8 It’s a shame that nobody feels the urge to do this, but only a snob would condemn them for it. Life’s hard enough as it is for most people, without piling on a load of homework.

A third caveat to what follows concerns mood and personal preference. It’s very difficult in these kinds of tests to compare like for like9 so the self and how it feels naturally slips into the gaps. Perhaps you hate graveyards? Or love yellow? Or maybe The Four Tops beat you up one night, and you’d rather listen to a computer sing than be reminded of it? Today you might be in a wet, Cezanny, Thursday morning kind of mood, and tomorrow feeling more hot, dry and Friday nighty, more erratically Van Goghish? All this may affect your choices — although I’d still say that a homemade blanquette de veau should always beat a ready-meal curry, even if you don’t like ‘fancy French food’.

Two more points before we proceed. Firstly, if you did well and are congratulating yourself, don’t forget that AI is still in its infancy. It will only get better and better, its ability to mimic human work ever more nuanced. What appears to be an easy decision now will soon be nearly impossible. If you did well today, try again next year. Sooner or later, as I’ll explore below, you’ll be unable to use either your mind or your feelings to discriminate between real and fake. Zooming in to paintings will only reveal more and more accurate details, fake art and literature will be based on more and more authentic sources,10 and human feelings, which are already easily stimulated by showy intensity than natural harmony,11 will be more and more cleverly manipulated.

Finally, I should say that I believe that the tools of the prison should be used against the prison, and that, with a great deal of caution, AI can be used for sorting data, for study and even for creative work. For the low art of satire, and for one-note visual jokes, for example, it’s pretty good…

The Sad and Beautiful Truth

With all these caveats in place (along with the possibility that you’ve already done one of these questions or happen to be familiar with King John or the work of Ravel), I would like to suggest, first of all, that if you got questions 1,2,5,6,9 and 10 wrong — in that you either preferred the artificial choice or couldn’t tell the difference — then something ain’t right. These sets are asking you to judge high quality literature, art and music which, unlike the poems, pictures and songs in the other questions, express the truth and depth of life. If this ‘feels off’ to you, if you are drawn to a machine-made simulation of the height of human achievement, I’d say you’ve got real cause for concern.

Take another look at question one, at the difference between Shakespeare’s ‘so foul a sky clears not without a storm’ and AI’s ‘the mind, like shadows, flits from thought to thought.’ Both of these are metaphors — the eye is like a storm, the mind is like a shadow — but the first is drawing a qualitative link between the two, founded on human experience. When you see a dark sky you know that it is unlikely to clear without a storm, and when you see a furious face you have the same intuition, that it needs some kind of violent release to ‘clear’. The pleasure of reading the Shakespearean metaphor is through realising the quality of the observation that unites two different realms of experience. If you dropped this quote into ordinary conversation at the right moment (after someone comments on the angry expression of a colleague for instance) in the right way (with a bit of irony to offset the pretension) you’d get a laugh.

The AI metaphor is purely quantitative; the mind moves and shadows move. That’s it. This plodding ‘observation’ (signposted with the word ‘like’) requires no direct, lived experience to make. It resembles ‘he ran like a dart.’ You don’t have to be a human being to notice that people running and darts flying move relatively quickly. If you used this metaphor in a casual conversation you’d get nothing more than a shrug, because it doesn’t require the quality of lived experience to recognise. The same can be said, analogously, for all the high quality images and songs here; they only makes sense because you know what it means to experience the life they express, and, conversely, they only seem indistinguishable because you don’t, because you’ve never really looked at a sky or at a human face.

The low quality art, the poems, images and songs in 3,4,7,8,11 and 12, do not require such experience to discriminate between the real and the fake, which makes aesthetic judgements between the options I have presented in these questions little more than a matter of chance. This is because the work in question, and our enjoyment of it, was already low quality. Here, AI hasn’t created the problem, it has merely reflected it back on us. The art we were making before the advent of AI was already artificial, which means that anyone who enjoyed that art — hollow pop for example (question 12), or bland wallpaper music (question 11), or tasteless shapes on a square (question 8)12, or tacky anime waifu (question 7), or second-rate poetry (questions 3 and 4) — will miss next to nothing in Chappy’s digital dystopia.13

Thus, when people assert that AI can match human creativity they are, caveats granted, advertising their own poverty of experience. Noah Carl, the author of this piece, on Aporia, is a good example. Before dismissing the disgruntled ‘cope’ of anti-Ai sentiment as a consequence of low status, he summarises the remarkable abilities of AI, by showing that it is proficient at technical (quantitative) tasks. The reason why humans rate university papers, business ideas, legal contracts and ‘frontier maths problems’ generated by AI higher than those created by humans is because the consciousness required to produce them is low. There is no need to be present, embodied and irrationally spontaneous to perform reasonably well at such trivial tasks. Carl, vaguely understanding this, then turns to the ‘creative arts’ where, he says, AI is superior to copyeditors, film executives and second-rate novelists. Can’t argue with that.

It’s not hard to counter Carl’s trivial argument, but his article does point to a wider problem; the inability of ordinary people to discriminate between the genuine and the fake in matters of real importance, a problem, as I say, which AI hasn’t created, but has highlighted. Poetry, art, acting and even conversation are routinely mistaken for AI, but this is not because AI matches human creativity, it’s because human consciousness has already been degraded to a level that makes human creativity, and judgements about that creativity, indistinguishable from artificial output. As Philip K. Dick pointed out;

The only way to determine whether someone was an android was empathy. What separated humans from androids was that androids had no sense of empathy. The difficulty was that very few humans did either.

Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep

The reason why, questions of literacy aside, a conscious reader can recognise that Shakespeare’s ‘so foul a sky clears not without a storm’ is a lovely line of poetry is because he has empathically experienced the qualitative reality behind stormy skies and stormy eyes. The reason why someone who is deeply familiar with nature knows that a hyper-cute AI image is fake14 is not because she has studied parrots, or even is fortunate enough to live in nature, it is because she is deeply familiar with her own nature. The reason why a conscious viewer knows that a certain AI-chosen colour is unusually vivid or ‘smooth’ is because she uses her eyes to sense out the inner quality of light, not because she is an expert in colour theory. True discrimination, between real and fake, between right and wrong, between life and death, is not a question of knowledge, but of empathy.

Without empathy we are not just at a loss when faced with the artificial intelligence of the machine, but before the artificial intelligence of the man. Witness the long and successful careers of hollow actors, for example, such as David Tennant, Ewen McGregor and Benedict Cumberbatch, who can only, at best, imitate real feelings.15 Witness the never-ending failures of discrimination that we have in our love lives, choosing one wrong ‘un after another. Witness the fawning adulation that the Royalty command, or the ease with which scammers, shysters and fraudsters prise money from us, or willing obedience. These are not failures of intelligence, but of empathy.

AI will never possess empathy, and so it will never know the difference between character and personality, between courtesy and politeness, between fooling and clowning, between curiosity and prying, between courage and recklessness, between idleness and boredom, between art and pornography, between abuse and offence, or between any other formally similar moral or aesthetic truth and mere rule following.16 AI doesn’t understand what it means to have empathic access to the inside of phenomena, and it never will. It can never consciously experience the context as a lived-in reality, which is why its rendering of the details that come from such a reality feel, on close inspection, so bizarre, giving the gestalt a feeling of wrongness.

And here we come to the heart of the problem — and the solution. Gestalt, in English, refers to a whole that is felt to be greater than the sum of its parts. The gestalt, the whole, is not apprehended piecemeal by the rational, relational mind, but is experienced at once by that which precedes such thought, one’s own ‘whole’. To take an example, the Scottish accent is comprised of a family of sounds (ʍ, ʔ, tj, ʉ, x, etc.) which fit together because they all ‘emerge’ from an embodied Scottishness which we can all enjoy. If you take one of those sounds and replace it with a foreign sound, the latter feels wrong. Not because, first of all, we know that it is not Scottish, but because we sense it is out of place.

Put a Japanese umeboshi plum on a pizza, or replace an unusual Shakespearian insult with a Jamaican cuss, or put a macaw in an English country garden, or add an electric piano to a chamber orchestra, and anyone with the capacity to sense gestalts will recognise that something is wrong here, something doesn’t fit. This isn’t to say that individuals and cultures cannot consciously take elements from each other in order to serve the gestalt, but that the gestalt does exist, that it precedes partial expression and that embodied consciousness of its violation is the means by which the genuine and the artificial is discerned.

Thus, as consciousness trickles out of the world, so does both uniqueness and discernment. The obliteration of cultural boundaries, the chaos of form that typifies the post-modern condition, no less than the dissolution of character into the kaleidoscope’s nightmare that comprises one’s daily death march through the feed, has made gestalt-awareness as rare as the individuals who embody it. The mood of the room, the particular quality of the day, the aura of her dress, as opposed to hers, of his gait as opposed to his, not only do few apperceive such part-preceding wholes — and are unable mourn their departure into a soup of broken images — but few are whole in the first place.

Consider where the art of Rembrandt came from — from Rembrandt himself. Consider the individuality of Beethoven, the man. Consider the characters of Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer. We enjoy such artists, musicians and comedians, and many like them, because they realised the pinnacle of individuality — of an undivided whole that precedes its divided parts. These artists had their influences of course, and they are embedded in a cultural milieu that their coevals share, but they are, first of all, unlike anything else in the universe. Those who suggest that AI, which can only ever be like something else in the universe, could produce the same quality of work as Rembrandt, Beethoven and Vic & Bob are saying, in effect, that the mind — what’s more the male mind, that invented and maintains AI — can give birth. Such arguments might be from atheists, but nothing has really changed since defenders of tribal religions first asserted that a male creator gave birth to the universe.

Thus, the true horror of AI is not that nobody can tell the difference between the genuine and the fake, although that is certainly tragic and depressing — if understandable and excusable — nor that we could one day be surrounded by artificially generated images, listening to artificially generated music and reading artificially generated stories, although that is certainly a horrific prospect. No, the worst of it is that the conscious whole, from which great art, great conversations, great characters, great lives emerge, no longer exists, and has been passing out of existence for a long time, leaving a culture that AI is not displacing, but actually improving. People will soon no longer care if something is real, or generated by a machine. Reality will no longer have value.

To put all this another way, there is a radical difference between awareness and consciousness. Awareness, or paying attention, is a technical act of concentration which isolates things from context and then compares them to other things. Consciousness however, or being attentive, is not an act at all, it is experience itself, panjective union, or oneness, with a context which thereby reveals its quality. The tragedy of the modern world, and the reason that quality is becoming so difficult to find within it, is not that machines can now pay attention as well as or even better than human beings, so that mere human awareness cannot tell the difference between the real and the fake, but that there is no consciousness to offer or recognise an alternative.

I’ve been speaking of ‘consciousness’, of ‘the whole’ and ‘the gestalt’, but you may have felt that these terms are rather clumsy. Why, if all this is such an important and intimate experience, don’t we have a less technical word to describe its degradation? Of course we do — two words in fact — but these, referring as they do to a quality of attention which barely exists, have also been degraded. It is, I suggest, time to experience again what these words refer to, not through study, of mere details, but through direct experience of the whole from which mere understanding of them arises. Such experience is available at any time, even now, especially now, only now.

The words are spirit and soul. That artificial intelligence cannot touch spirit and soul is the reason why nothing that it can kill is worth preserving.

Further Reading

Because the infrastructure to hold it in place is in terminal decline, because we have outrun its resource base, because the financial system is on the point of a crash ‘far exceeding anything experienced in 2008-09’ and because nature and human nature are, in the final reckoning, indomitable.

You might recognise some of the original works of art, and you might also have done a couple of the questions before, which were taken from other Turing tests on the internet, but in any case, you should get the idea.

With thanks to Scott Alexander’s ‘Ai Art Turing Test’, from which the first two AI images are taken.

And perhaps sense the feeling of the strokes. With impressionist work, which uses texture to communicates the feeling of the artist, this is particularly easy. It will be a long time before AI can reproduce, even crudely, this…

I mean the actual sensate thing, with bumps and grooves, not its screen simulacra.

Or if you look closely at AI-generated hands which, like those drawn by any other second-rate artist, are not the work of someone actually with hands.

I am referring here to the history of Western art and literature, the roots of everyone who was born and grew up in the West, regardless of their ethnic background.

They usually feel vaguely embarrassed about this and sometimes, in my experience, uncomfortable. I explain why in my enquiry into taste.

This is why I am assuming that readers of my work will do better than most. You good people read, for one thing, which is not a very popular activity now, and I assume you also listen to decent music. Enjoying art, unfortunately, is a niche activity even among cultured folk, but if you’ve ‘worked on’ your taste at all, you’ll likely have a better eye or ear than those who have not.

One of the reasons that the Motown song is relatively easy is not just because of the passionate quality of the Four Tops, but because the songs are from the same album, while the AI impressionism question is a little more difficult because it asks you compare Cézanne to a Van Gogh-style image. In fact there is a genuine Van Gogh that looks like the AI here…

…but it’s so famous and so obviously genuine, that it would give the game away.

Today, Ghibli and Nabokov, tomorrow Matsumoto and Joyce.

Which is why leather is sprayed with the smell of fake leather, why fake ‘clean’ smells are added to scent-free cleaning products and why synthetic vanilla is preferred over real vanilla.

Not that all abstract impressionism is tasteless. The placeholder image for this essay, Kandinsky’s Circles in a Circle, for example, is lovely. Being technically less nuanced than Raphael, however, I can imagine AI getting very close to this, very soon.

But again, not quite matching it, unless it literally copies Kandinsky, but then it wouldn’t be original.

This, by the way, is a good thing. The ‘artists’ who are put out of work by AI are those who were already polluting our cultural spaces. Unfortunately they won’t be replaced by a trickle of identical pap, but a cosmic avalanche.

Such as these abominations…

William Barker comments…

My own tuppenceworth is that this is like when somebody you meet is ‘playing a role’, rather than being the fullness of who they really are. Others might know that something is wrong, but they still cannot suss that person out. It’ss because they are only presented with a role, which is uni-dimensional; it doesn’t have the backing of a whole, multi-dimensional human behind it. To a sensitive person, having to play a role like that feels claustrophobic, awful in fact (unless we are talking about a very brief jokey mimic). Of course, a good actor can play a role successfully, but only when they fold the fullness of who they are into the mix. If not, they rely on a forced and very short list of mere traits which do not a human equal, this is immediately or eventually sniffed out by a perceptive audience.

See The Apocalypedia and Self and Unself for further discussion.