Noam Chomsky’s prestige is falling, but he is still in some respects a figurehead of leftism, a popular ideology which, within certain limits, offers useful critiques of state-corporate control. Beyond those limits however socialism reveals itself to be part of the system and even, to the degree that it marks out the limits of acceptable dissent, an integral part of it. In Chomsky’s case this became all too clear during the lockdown era, when he told us that the unvaccinated should ‘remove themselves from society’ and, if they should starve, well, that was ‘their problem’. From an anarchist perspective however, Chomsky’s authoritarian socialism was evident long ago. Here, if you haven’t already read it, is my (lightly revised) pre-lockdown critique, written in 2018…

Chomskyan Anarchism

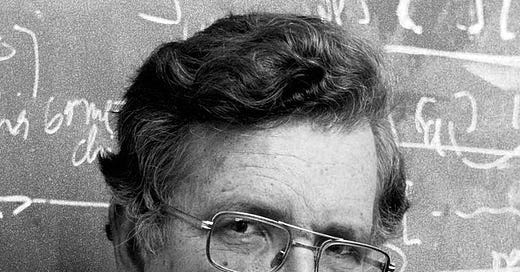

Noam Chomsky is a reasonably important intellectual — although idolised out of all proportion to his actual contribution to human understanding — who has written potent critiques of US foreign policy, clarified the nature of intellectual conformity and social programming and has done a great deal of good helping victims of capitalism. But, despite what he says, he is not an anarchist. This is not a question of doctrinal hair-splitting, it gets to the root of Chomsky’s system-friendly authoritarianism and that of the left he represents; for anarchism is the only way of life which has ever worked, or ever can, and distorting it or drastically limiting it, as Chomsky does, reduces its range, subtlety and power.

To say that Noam Chomsky is not an anarchist, that he is socialist who has adopted and adapted anarcho-syndicalist ideas, is not to offer a semantic or doctrinal argument, faffing about with the in-group fighting that infects radical politics. Here ‘anarchism’ and ‘socialism’ are used to highlight the poverty and the weakness of Chomsky’s thought when it comes to matters of profound importance to all of us; state-corporate control, democracy, professional authority, technology, civilisation and, the foundation of all these forms of domination, the human ego, none of which can be grasped within the socialist framework, because socialism is, insofar as it is civilised, statist, technocratic, professional and democratic, an authoritarian ideology.

Noam Chomsky, like all socialists — and unlike all anarchists — supports the state. He has said that the task of dissidents is to strengthen the state,1 he has apparently declared that there is nothing inherently wrong with the state,2 and he has given often indiscriminate support to numerous left-wing and socialist states (such as his infamous, if accidental,3 and dishonestly caricatured,4 support of the Khmer Rouge). His extremely vague ideas about a revolutionary society appear to presuppose a state.5 He votes, and frequently recommends voting; for Hilary Clinton for example, and Joe Biden. He is in favour of statist globalisation.6 And he holds a distinguished position in the US state-corporate system (funded, for many years, by the pentagon). He told me he spent 70 years working to overturn this system, and yet astonishingly, and conveniently, all that time he managed to keep his job.

This doesn’t mean that it is necessarily wrong to, at least occasionally, support a socialist state, vote in an election (or, as Chomsky says, spend a second putting a cross on a piece of paper then go back to the real work of activism), or keep your nice job at an extremely prestigious university. I think a pretty good case can be made that these things are wrong,7 but they are not anarchist acts, as Chomsky himself recognises. Neither is having an enormous amount of money, as Chomsky does,8 and as he also recognises. He pointed out to me that having vast wealth is an un-anarchist state of affairs, which of course I agreed with. I added that having a lot of money could still be classed as moral or fair if you give your money away or spend it anarchically (which doesn’t mean on anarchists of course). Chomsky’s reply to me? ‘I imagine I do [this] far more than your heroes.’

Chomsky is also a socialist because he supports professionalism. Not the acts of particular journalists, teachers, lawyers and so on, which he is bitterly (and sometimes brilliantly) critical of, but the existence of a professional class. He supports schooling, for example — when asked about his views on Ivan Illich: he said ‘deschooling society is taking away from people some of their major opportunities for individual growth and social interaction.’ I asked Chomsky about Illich, but he wasn’t interested. He said he has spent fifty years ‘critiquing the work of academic intellectuals’ (emphasis mine). His response to the idea that their existence is inherently problematic; ‘I don’t see it’.

Chomsky is also a socialist, or leftist, because he supports democracy. Not just by voting, but generally, uncritically. The many anarchist critiques of democracy9 do not interest him, nor does the idea, often expressed, that ‘no conception of anarchism is further from the truth than that which regards it as an extreme form of democracy’.10 In the real world, democracy, or the dictatorship of the 51%, is a form of authoritarianism invented to manage masses, not to liberate them, and which presupposes compulsion (what do you do with the 49%?), dissolves responsibility (everyone can always blame someone else in a democracy) and proliferates mediocrity and mob-rule (if nine out of ten people want smartphones, then smartphones we must have!).

All these positions put Chomsky squarely in the socialist zone of the political spectrum. His other views either place him well within socialism or at the most socialist extreme of anarchism. For example, like some anarchists, but all Marxists, Chomsky is a technophile. He has no interest in the kind of analyses offered by Lewis Mumford, Jacques Ellul, Ivan Illich, Fredy Perlman, Ted Kaczynski or John Zerzan, he has apparently said that cars and robotics are fine,11 that ‘much socially necessary work can be confined to machines’ and that technology is neutral, a patent and quite insane falsehood.12

Likewise, like some anarchists but all socialists, Chomsky has an uncritical approach to civilisation. The catastrophe of agriculture, the limitations of civilised language, literacy and symbolic thought, the means by which civilisation domesticates and infantilises man — particularly through inherently ruinous [industrial] technology — the various forms of (entirely anarchic) resistance to civilisation that have arisen throughout its ten thousand year history;13 none of these concerns — those of primalists like myself — interest Chomsky. His response (to me), was ‘just tell 7 billion people in the world that the problem is that they exist’, and that [these ideas] are ‘completely irrelevant for the modern world for perfectly obvious reasons.’ I pointed out that no sane anarcho-primitivist recommends the entire world immediately returning to the trees, that anarcho-primitivism focuses on how small groups were able to maintain egalitarian relations with each other (including egalitarian sexual relations), how they reached decisions together (without voting), how they managed to cooperate together (perhaps the word ‘federate’ could be used) why so-called ‘mental illness’ did not arise, or coercive control, their ‘relationship’ with nature and culture (which appeared to be the same thing), their diet and their psychology; all of which are very relevant to the modern world, ‘for perfectly obvious reasons’. Not obvious to Chomsky though, who sees in all this nothing more than a recommendation for mass genocide,14 the ravings of those ‘way out on the fringe’.

Another attitude of Chomsky which puts him at the disastrously socialist end of anarchism is his hyper-reductive rationalism,15 which in his case is particularly extreme, not to mention dour. He has a total lack of interest in the arts, or in comedy (which he told me was ‘way out at the margins of the lives of almost all people’), or in religion (which he offers an extremely crude critique of, focusing, like Dawkins and Hitchens do, entirely on Abrahamic absurdities), or in love, or in death, or in sex or in gender. None of these things are important. They are outside the ‘serious’ concerns of anarchists. Anarchist authors like Shelley, Tolstoy, Morris and Wilde,16 revolutionary artistic movements (such as situationism — or even Monty Python), revolutionary spiritual movements (such as the radical Christian revolts of the late middle ages), along with the teachings of people like Chuang Tzu and Jesus of Nazareth… none of this is sufficiently ‘serious’. Chomsky draws his very serious philosophy from the ‘enlightenment,’ one of the most horrific periods in world history. The disastrous legacy of its chief thinkers — Chomskian heroes Descartes, Locke, Humbolt and Hume17 — we are living with now, but which, for Chomsky, is ‘very positive.’

Finally, of the ideas which situate Chomsky at the Marxist end of anarchism, we turn to anarcho-syndicalism. This is the ‘workist’ belief — largely grounded in nineteenth century thought — that a better world can be built through the activity of powerful worker-run unions and democratic, mainly industrial working-class organisation and agitation. This socialist ambition is not just a subset of the principles of anarchism or of classic currents of anarchist thought — which stress total decentralisation of power, and a far wider conception of revolutionary activity than working-class organisations — but has frequently been in opposition to it.

Anarcho-syndicalism inspired the most successful anarchist revolution of modern times, the Spanish revolution, and it does have much to recommend it, particularly in its ‘looser’ forms. It’s hard to imagine a factory — if such a thing really can exist in a sane world, which is unlikely — intelligently operating any other way. But it remains a limited, largely communist, ‘work-based,’ civilised, reformist and bourgeois subset18 within the anarchist tradition.

Chomsky’s favourite modern anarchists are anarcho-syndicalists; specifically Rudolf Rocker and Daniel Guérin. Guérin, for whose history of anarchism Chomsky wrote an introduction, was a communist who came to embrace anarcho-syndicalism; which he called ‘the path of reality’. For Guérin, for whom anarchism started with Bakunin, ended at the Spanish civil war, and is comprised entirely of the trade-union movement and syndicalist agitation, everything else — such as the ‘utopian’ ideas of Peter Kropotkin, or the critiques of anarcho-syndicalism by Enrico Malatesta — is ‘sectarian’ or ‘purist’ fantasy, or simply does not exist. It’s not on his and Chomsky’s non-sectarian ‘path of reality’.

George Woodcock, one of the finest anarchist writers of the twentieth century, whose history of anarchism is a well-regarded classic, and whom Chomsky claims to admire, suggested that Chomsky calls himself an anarchist19 because he is embarrassed by statist communism and wishes to mitigate its contradictions and absurdities by borrowing from anarchism. This seems very likely to me, almost certain, but in any case, Woodcock is correct; by borrowing in this way Chomsky tragically diminishes the potency and scope of that which claims to be representing, ‘reducing it from a comprehensive philosophy of living, embodying [amongst other things] a many-sided strategy of social change, to a mere cluster of tactical concepts’. Chomsky finds Woodcock’s claim that he is ‘not an anarchist by any known criterion’ to be outrageous ‘sectarian dogmatism’. He says that Woodcock is decreeing, from on high, what anarchism is, and ruling out Chomsky’s anarchism from a position of intolerable inflexibility.

Chomsky isn’t inflexible though, or sectarian, or a ‘purist’. Oh no! Anarchism has, in his words, ‘a broad back’. It just doesn’t include any artists or comedians, any anarcho-primitivists, hardly any anarchist thinkers of the past fifty years, any radical critics of democracy or technology or civilisation, or anything at all prior to the writings of Proudhon, including anything relating to the most successful anarchist societies of all time, those which humans lived in for several hundred thousand years prior to civilisation.

Some elements of Chomsky’s thought are anarchist — and so, strictly speaking (something that Chomsky does a lot, strictly speak), Woodcock may be wrong — but in a limited and highly socialist-friendly sense. The rest is out-and-out socialism or leftism, a chronically impoverished and highly destructive nexus of ideologies which may, like Chomsky’s own work, alleviate the agonies of poor peasants in far-away places, offer fine media criticism and denounce American foreign policy, but cannot wake us up from the nightmare we are living under, because, like the right-wing ideas it sets itself up against but blends into, it cannot even perceive it.

Chomskyan Language

Language, for Chomsky amounts to ‘knowledge of recursive syntax that cannot be explained by logic, history, culture, society, physics, or any experience of the speaker outside of the mastery of their native language before puberty.’20 His theories do not engage with existential reality — the context from which meaning emerges. Metaphor, tone, implication, empathy and human society are all absent from Chomsky’s analysis, which is unable to explain language except in the most banal, utilitarian sense.21 His grammar does not include or involve consciousness in any meaningful way, nor anything else that is recognisably human. All that we think and say boils down to computer code in a machine.

In 2016 Chris Knight discussed the failures of Chomsky’s grammar in Decoding Chomsky, which places Chomsky’s linguistics within the context of his academic career at MIT, a massive technocratic institution heavily embedded in, and for significant periods, well funded by the US military-industrial machine. Naturally, this doesn’t necessarily invalidate Chomsky’s theories, but it does explain their appeal to the system, which is heavily invested in a reductionist and entirely technocratic idea of language and meaning, one that can be machine encoded, reproduced, transmitted, manipulated, made and remade.22

Chomskian linguistics reduce ‘the language faculty’ (a telling expression) to a kind of computer and meaning to the binary-digital framework of a mathematically pure vision of language. This has other problems, apart from the iffy moral consequences which Knight focuses on. One is that it is beyond ridiculous. Did you know that Noam Chomsky, the genius that he is, believes that ‘carburettor’ and ‘bureaucrat’ are innate concepts? He really does! Listen:

Furthermore, there is good reason to suppose that the argument (that children learn language so quickly because they already know what words mean) is at least in substantial measure correct even for such words as carburetor and bureaucrat, which, in fact, pose the familiar problem of poverty of stimulus if we attend carefully to the enormous gap between what we know and the evidence on the basis of which we know it… However surprising the conclusion may be that nature has provided us with an innate stock of concepts, and that the child’s task is to discover their labels, the empirical facts appear to leave open few other possibilities.

That is quite surprising professor. Daniel Dennett was shocked too, that ‘Aristotle had an innate airplane concept… a concept of wide-bodied jumbo jet [and] the concept of an APEX fare Boston/London round trip?’ I’m not one to dismiss insane-sounding ideas, and I even believe that, in some way, everyone has access to all experience, but that children are born with a ‘conceptual structure’23 which requires experience to activate, that context and consciousness, much less shared social meaning, are irrelevant to meaning, is risible for what must be obvious reasons. Again, obvious to everyone but Chomsky, because if he accepts that ‘carburetor’ and ‘bureaucrat’ are acquired from experience, his ‘faculty’ — both the institutional one he worked in and the conceptual one he theorised about — would collapse.

Another non-trivial problem with Chomsky’s theories is that they don’t work and have been shown to be wrong; these include such key ideas such ‘deep structure’, ‘surface structure’, ‘meaning-preservation’, ‘transformational rules’, ‘universal grammar’, the ‘structure preservation principle’ and so on, all which have all been abandoned… by Noam Chomsky! Not that this bothers him; he’s not interested in testing his ideas or referring to them to conscious reality.

There’s little point then in studying Chomskyan grammar, partly because Chomsky himself has turned his back on it, and partly because it is beyond the ken of mortals. Chomsky, who, continually criticises Orwellian Newspeak wraps his output up in insanely complex technical terms of his own devising, robbing ordinary language of its power to express reality or of ordinary people to understand their own speech. This is Illichian Newspeak. Chomsky says the ordinary use of language ‘is a totally useless concept’, that really it is a system of rules which we need specialist minds to uncover, and in fact is (get this) not even a means of communication. The idea that it is, is a ‘dogma’, a silly relic from yesteryear propounded by people who don’t understand that the entire purpose of language is to talk to yourself, and that the study of language must be left in the hands of responsible specialists with the correct training; ordinary people are not invited. How anarchist.

For Chomsky, reality incarnate, the nature of consciousness, the actual world of humans, culture and all our attempts to experience and express what is most important and true in life have no significant bearing on language, communication and meaning, just as they have no significant bearing on Chomsky’s life. He, like most people who have spent their lives in institutions, has very little to say about any of these things. What he does say, quite rightly, is that science has nothing to say on matters of real importance to human beings, such as society, consciousness, death, beauty or any other existential, aesthetic or ethical reality. Here it is Knight, faithful to Marx’s monstrous belief that life and science should rest on the same materialist basis, whose views are distorted, while Chomsky’s humble realism is salutary (although that doesn’t stop him endorsing preposterous illusions like ‘Universal Moral Grammar’). Science is, as Chomsky says, extremely, outrageously, limited; but this certainly doesn’t mean that the questions that scientists pointlessly ask — What is consciousness? What is love? What is morality? How did the universe begin? How did life begin? — are impossible to solve, or, as Chomsky continually tells us (for example in his address to the Vatican), forever beyond us. They are beyond Chomsky though, for sure, as he never asks them.

Chomskyan Radicalism

Chomsky’s account of language has often been seen as distinct from his politics, but actually they are one and the same, for in both meaning — freedom, love, truth, conscious experience and so on — is ruled out by the civilised institutional framework which the professional simply takes for granted. Lip service is given to meaning while working non-stop to deprive it from freely emerging from the only place it can, beyond the professionally managed institution, in the natural consciousness of free people. This ‘stagversive’ activity, confusing ordinary people, depriving them of the means of controlling or even experiencing their own lives, while posing as their champions, is not just tolerated by the system but actively condoned by it.

Chomsky once wrote:

‘If I started getting public media exposure, I'd think I were doing something wrong. Why should any system of power offer opportunities to people who are trying to undermine it? That would be crazy.’

And yet he was employed for his entire career by one of the most powerful and prestigious universities in the world — quite an opportunity — and for many years funded directly by the pentagon: only possible because, in his horrible universe, language is a morality-free, culture-free, context-free, meaning-free computer code. The pre-eminent system of world-power gave him extraordinary professional24 opportunities because, in his work on language, he was useful, safe, without the power to radically threaten those who dominate language.

Chomsky is an enormously popular writer and speaker. His lectures and books sell out (Dana O’Hare of Pluto Press said, apparently: ‘All we have to do is put Chomsky’s name on a book and it sells out immediately!’). He has somehow managed to find a way to appear in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Guardian and on the BBC. He has hobnobbed with the rich and powerful (including, most notoriously, Jeffrey Epstein25) and is now a very wealthy man. Until he effectively retired, he was everywhere.

Could he, by his own logic, have been, all this time, ‘doing something wrong’? More and more of his supporters think so. Since the pandemic a large section of the left, those who are actually, rather than theoretically, opposed to authoritarian coercion, have stopped paying attention to him and to the rest of the middle class he spoke for when he supported professionally-managed biofascism. The left, those who confine their revolutionary ire to statist politics, US foreign policy and the herdthink of journalism, still read him, because he does have something to say about these things26 but their number is shrinking with Chomsky’s credibility.

Many now recognise Chomsky, the linguist, to be an extremely aggressive disputant,27 who regularly mischaracterises his opponent’s positions28 and, while considering himself a genius,29 offers flawed theories, subject to constant revision30 and couched in the most obscure, impenetrable language imaginable. The reputation of Chomsky the radical leftist is even lower. He was, like most of the left, happy for the state to impose coercive lockdowns and experimental ‘vaccines’, he has nothing meaningful to say about the dystopia forming around us, nor about the wider civilised system that this nightmare is the culmination of. This is why he is and has long been given a platform; he is a professional radical. He can be counted on to criticise overt, capitalist power while maintaining the covert system of professional management it depends on. If his analysis extended beyond the professional system, if his understanding of language penetrated the well-spring of meaning, if his radicalism really were trying to ‘undermine systems of power’ or if his philosophy touched the human spirit, the nature of consciousness or any other ‘irrelevant’ question ‘way out on the fringe’, he would have been be ignored while alive and remembered after he died. As it is, the opposite will be true.

He just waves away objections that corporate power (to to mention egoic power) arises from and would inevitably co-opt a stronger state. He says that abolishing the state is ‘not a strategy’ — that it can’t be done. It certainly can’t be done with that attitude Noam! In any case, it certainly will be done, and very soon.

According to John Zerzan, who mentions a date of 28th January 1988 for this claim. I can’t find the source, but it is consonant with Chomsky’s outlook. Zerzan was also behind lockdowns and vaccinations, but his critique of Chomsky stands.

In that he didn’t know the atrocities the KR were committing and obviously if he had, he would have condemned them. The problem was they he assumed there were no such crimes and dishonestly tried to discredit reports that there were.

Much like his noble and unwavering support for free speech, even for voices he despises, such as holocaust denier Robert Faurisson whose right to be published Chomsky defended.

Appear: I’m not entirely sure they do. Bob Black (another leftist lockdowner) makes a fairly good case for Chomsky’s support for law and national planning being statist.

He is for globalisation, and anyone who isn’t, is a ‘dedicated hermit’, and he supports the state, the strategy of eliminating it being ‘back [at] the level of “let’s have peace and justice”’.

Even, according to Guérin, the Spanish anarchists said voting was wrong.

Apparently he invests in all sorts of shady places, but I have no idea.

George Woodcock.

Again according to Zerzan, although again I can’t find a source.

Chomsky: ‘Technology is usually fairly neutral. It’s like a hammer, which can be used to build a house or to destroy someone’s home. The hammer doesn’t care. It is almost always up to us to determine whether the technology is good or bad.’ The stupidity of this position — completely ignoring how hammers have to be made, how society has to be deformed in order to make them, and how they interfere with the social relations and even the consciousness of their users — has been exposed time and time and again; of no interest to Chomsky.

Such as described by James C.Scott — whose work Chomsky claims is not criticising civilisation.

Here I am talking about Chomsky’s approach to reality, not his specific philosophy, which is a mix of rationalism (basing opinions on reason and logic, rather than on emotion or religious belief) and empiricism (appealing to the objective, sensory world for evidence; as well as ‘the passions.’). Actually both of these are fundamentally the same; the former takes isolated, relative, egoic thoughts as the acme of truth, the latter takes isolated, relative, egoic emotions, sensory experiences and the like, as the basis for reality. Both are isolated, relative and egoic. I attempted to point this out to Chomsky. His response: ‘I am not understanding what you have in mind’.

Wilde, Morris and Tolstoy either called themselves socialists or did not identify as anarchists; but an enormous amount of what they said was anarchistic.

He doesn’t cite enlightenment celebrities Voltaire, Comte and Bentham. I wonder why?

One that is, it must be added, increasingly irrelevant in the distributed world of late-stage capitalism.[

Although Chomsky calls himself an anarchist he doesn’t actually say a whole lot more. His anarchist writings form a minuscule body of work. You could fit his entire output on anarchism, over seventy-odd ludicrously prolific years, into a slim, 200 page, volume. Which is what Penguin did.

See Understanding Psychotic Speech: Beyond Freud and Chomsky, by Elaine Ostrach Chaika.

Chomsky complained Knight’s ‘crucial charge’ is false because he, Chomsky, already viewed language as a kind of code, long before he was employed by MIT, but of course the issue is not that his work was intended for military use but that it already fit with the requirements, demands and fundamental philosophy of the US military. Obviously it did; if it was useless and antagonistic, funding would have been withdrawn. The military was and is heavily invested in precisely the same elitist technocratic reductionism as Chomsky, which is why they were interested in his technolotrous, reductionist idea of language. Knight suggests that this was the real reason for the cultural shift away from behaviourism which Chomsky spearheaded; such requirements as the military had are incomprehensible within behaviourist frameworks.

In New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind; my emphasis.

Noam Chomsky is a member of the socialist professional class, which takes no account of society, nature, consciousness or any kind of reality beyond the abstract and abstractable things they manage. The professional spends his life in institutions and sees reality through the bodiless concepts that institutions reward and manufacture. Society, for the professional, is a kind of machine, life also, which we need the professional technocrat to conceptualise and to manage, an ideology we know as ‘socialism’, the ideology of management.

Socialism has much to say about working people controlling their own destinies, and about the state ‘withering away’ in the future, but it rests on the unspoken assumption that the wondrous society that socialist techniques will create requires powerful institutions and powerful machines — and therefore powerful professionals — to run it. One can therefore only speak of being an anarchist under conditions of professionally-managed modernity in the same way that one can speak of being a peaceful democrat or a charitable capitalist.

This is why the leftist falls in step with the rightist when faced with a threat which originates from outside the system, for although the right-wing seeks to own the machine and the leftist to manage it, both are entirely dependent on it. Radical critiques of the system never come from either the left or the right, but from a position entirely outside the so-called political spectrum — which is really just a squabble about how best to exploit people.

A very unsavoury character, Epstein. Here’s Whitney Webb’s assessment of these meetings, although she ropes in Woody Allen who — I mean, I don’t know and I don’t care — but, I’ve read Allen’s autobiography and watched a few vids, and it’s very hard to be sure that he is guilty of what he has been accused of. There are a lot of dodgy folk in the entertainment industry, but the certainty of liberal-minded armchair juries, happy to convict anyone of the most heinous sex crimes, based on flimsy evidence, gives me moral dyspepsia.

Just as Pilger, does, and Greenwald, Media Lens, Cook, Caitlin Jonstone, Hedges and the rest of the lockdown left.

He is fond of characterising his opponent’s views as schizophrenic, pathological and so on. Randy Harris in ‘The Linguistics Wars’ wrote ‘Chomsky can, and often does, sling mud with abandon. His published comments can be extremely dismissive, his private comments can reach startling levels of contempt’.

‘Chomsky’s tendency to misrepresent others’ views has become notorious’ (Hall 1978:86)

‘Very few people recognise themselves in the representations Chomsky gives of their arguments.’ (Harris, ibid)

‘Again and again, Chomsky’s critics claimed that he chose data to support his theories but then discarded it when it no longer suited, and that he intentionally misinterpreted his adversaries and then launched an attack against his own misunderstanding’ (Kenneally 2007:34)

When journalists Ved Mehta asked Chomsky who were the leading figures in linguistics he replied that ‘there aren't any’. (1971:191) and when Christopher Hitchens asked him who his co thinkers were, he wrote ‘I do not regard myself as having any’. I’ve got no problem with complete intellectual self-confidence; but based here on what exactly?

‘Much of the lavish praise heaped on his work is, we believe, driven by uncritical acceptance (often by nonlinguists) of claims and promises made during the early years of his academic activity; the claims have by now largely proved to be wrong or without real content, and the promises have gone unfulfilled.’ (Levine & Postal, 2004), a view echoed by Frederick Newmeyer, Geoffrey Sampson, Chris Knight and others.