The system cannot function unless there is never enough. This we call scarcity, which is the opposite of plenitude, or abundance · · · The system must make the reality of abundance impossible to depend on and the idea of it impossible to take seriously · · · The inevitable end-point of the system is a reality in which everything is a ‘scarce resource’, including jobs, air, water, time, affection and even conscious awareness of one’s own body.

We can’t afford it, there is just not enough money. There is also just not enough food, enough energy, enough jobs, enough houses, enough space or enough time. Just as we invent money and then see the world as colourless ideas (sleeping furiously), so we invent capitalism and see the world as a battle for finite resources. The entire universe is reconfigured as a mind-knowable system of facts and all of nature as a war of all against everything for scarce objects. And all this, most extraordinarily, is how it has to be. Just as things can only be sold by being rationally ripped from context, so they can only be bought when they are scarce. The market cannot function unless there is not enough, and so it must ceaselessly work to make sure that nobody ever has enough. If food, water, energy and opportunities for meaningful and enjoyable activity are plentiful there is no need to produce commodities at work or consume them at play. If time is abundant, if space freely available, if necessities are within reach, why bother working for them? Why bother saving them up? Everything crash!

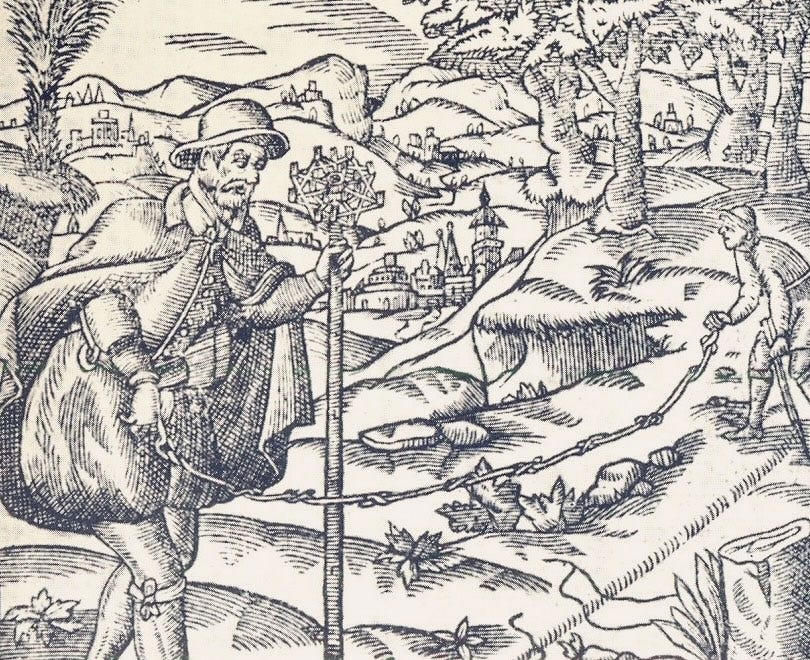

In the real world—a place, alas, so far from most people’s experience it appears to them as dreams do—scarcity does not exist. The natural state of man and woman is endless affluence, or abundance. This is not, as the systems-man would like to believe, an airy-fairy fantasy, but a demonstrable fact. Scarcity, along with gruelling toil for subsistence, was unknown before civilisation, and was unknown in those societies which, until recently, survived outside of it.1 Observers of non-sedentary, immediate-return foragers are frequently astounded at the profligacy and faith in the future of people who are only ever a few days away from starvation.2 Even medieval society did not consider the commons scarce, let alone space or time. It was only when ‘civilisation’ began generating needs, and when capitalism began multiplying them—only when the monolithic system began curtailing access to necessities and capitalism began annihilating them—that human existence filled up with infinitely increasing desires for ever dwindling resources; a word which, in modern usage, always implies something there can never be enough of.

Thus, what is called ‘production’ means withdrawing capital from circulation in order to ensure a high rate of return on that which is permitted to dribble out through ‘investment’, thereby guaranteeing inequality. Thus, ‘education’ means learning under the false assumption that knowledge is a scarce product manufactured in an artificial ‘reality’ in which opportunities to use that knowledge, in the activity we call ‘work’, are also scarce. Thus, ‘travel’ means locomotion under an imposed need to gain access to scarce road, rail and flight resources and to consume scarce energy resources in order to access scarce production or consumption resources placed artificially far away. Thus, ‘aid’ means depriving foreign people of the means of subsistence.3 Thus, ‘health’ means access to artificially scarce medical resources, ‘society’ means access to scarce bandwidth, and scarce free time, ‘love’ means access to scarce mating stock (particularly scarce eggs), ‘work’ means access to scarce jobs, ‘achievement’ means access to scarce media attention (or scarce prizes), ‘wealth’ means access to scarce money and ‘truth’ means access to scarce facts, or to scarce ‘learning resources’.

To put this another way, although there are natural limits to productive human activity (above all the irreversible nature of energy use; energy becomes less available for work as entropy increases) and although disregarding those limits leads to destructive and unsustainable growth-at-all-costs, scarcity, not having enough of what we actually need to live, and to live well, is not a natural condition, and must be unnaturally manufactured by a system that depends on scarcity to function by dismantling whatever mode of life stands in its way. If a group of people share their surplus, they will have to be made poor so that they are forced to put that surplus on the market. If a society meets its transport needs, for example, or its health needs, or education needs, then their transport, health and education systems will have to be destroyed. If human beings are quite comfortable with their lives, they must be made uncomfortable; dependent on needs which only the market can satisfy.

All of which, under a late-stage market system, is inevitable. A usurious, technocratic, debt economy which forces everyone to pay not just more than they have, but more than exists, inevitably creates a quenchless thirst to produce and consume our way through a diminishing world of quantifiable resources artificially generated by tearing them from their context and then rendering them as money values. It also creates a huge number of institutions which, in order to survive, must multiply needs and artificially impose deficiencies; which is to say create needy, deficient people, which must then be cared for by caring people. The disabling system and the crippled men and women it produces, crawling over each other in order to obtain their share of an artificially shrinking pie, is therefore masked by the service, aid and the tireless altruism of professionals employed to care for them.

We are told that we cannot take care of our land, or leave nature alone, or build nice houses for everyone, or care for each other, or produce marvellous tools for ordinary people to use... because there is ‘not enough money’. ‘The state’, Margaret Thatcher told us, ‘has no source of it; it all comes from what we earn’. And yet, amazingly, these same poor states, affected by the 2008 financial crash, and by the 2020 system-enhancing, poor annihilating lockdown, found trillions of dollars to keep the economy afloat. When the poor need to be disciplined, it’s time for monkish, belt-tightening ‘austerity’, but when the system needs money, suddenly there’s an infinite, unquenchable, supernatural supply of it.

In actual fact, money is one of the key means by which the power of men and women to live is made scarce by the system, which cannot survive unless abundant educational opportunities become scarce resources (provided by ‘the best schools’), abundant health becomes a scarce resource (recovered in ‘world-class’ clinics or maintained at expensive gyms and delis), abundant care for the elderly becomes a scarce resource (‘sorry dear, no time to stop and chat, got to clean forty more rooms today’), abundant places for children to play become scarce resources (which must be protected from ever circling paedophiles and the dreaded lurgy), abundant physical affection becomes a scarce resource (Authentic Girlfriend Experience, £240 an hour), abundant water becomes a scarce resource (shipped from the antipodes), abundant nature becomes a scarce, not to mention intensely managed, resource4 and abundant life is constantly trickling away. Even the opportunity to inhabit our own bodies, to rest, to idle, even to sleep, even this, to exist in our very selves, must be a scarce resource under the system in its most highly developed form.

We may never reach the capitalist utopia of pay-per-use bodily organs with operating systems which must be installed every six months, of chairs which decay like mushrooms and have to be reprinted every half-hour, of idea-rental and sunlight-meters and water extracted from the moons of Mars, but there can be only one way forward for the technocratic market system; permanent, omnipresent existential scarcity, a nightmarish, computer game of endlessly proliferating bar-charts which not only never stop diminishing, but are used up at ever faster rates; and any attempt to stop this process, or even slow it down, is, ipso facto, criminal or insane.

Ultimately, the process cannot be stopped while its fuel and foundations remain unaddressed. These reach far deeper than the predatory, mechanical and exponentially wasteful system. Scarcity, after all, can only apply to things; to isolated objects separated from context and consciousness. Meaning, truth, love and life are qualities, and, as such, are inexhaustible. It makes as much sense to talk about ‘acquiring’ love or ‘running out’ of truth, as it does to talk about the present moment as a ‘resource’ which needs to be ‘managed’. This is why those who own and manage the system have, from its earliest days, expended immense intellectual efforts in converting qualities into objects; to knowledge-objects, truth-objects, quality-objects, and the like, for only this way can life come under control. This is why we are told to view God as a person with wishes and desires, karma as a cause-and-effect law, memory as a text stored in the mind, happiness as a chemical produced from amino acids, ethics as a collection of things in people’s heads which, like ‘fibre-optics’, must be managed for optimal efficiency, nature as a resource which can and must be exploited for our comfort, satisfaction and security, and meaning as a pile of ideas which I can empty out of my brain-pocket and into yours (and which ‘intelligent’ people are sitting on sacks of).

This is not a conscious process. The brains in jars that manage the system’s intellectual and cultural industries are unable to see reality any other way, nor are the domesticants who live in the thing-world they have helped create. They too are things.

You have been reading an extract (Myth 3) from a newly updated…

33 Myths of the System

As civilisation reaches endgame and begins to disintegrate, as the illusions of left and right coalesce into a single, spectacular omnimyth, as every rootless mind begins to experience the stupefying dystopias of Orwell, Huxley, Kafka and Dick, the time has come to understand the whole system, from root to fruit.

The classic account of ‘primitive affluence’ is Marshall Sahlins’ The Original Affluent Society, which demonstrated that modern scarcity and hard work are unknown in pre-civilised societies. Sahlins’ work is generally accepted as accurate, if limited, over enthusiastic and a tad sloppy (see T. Kaczynski’s corrective, The Truth about Primitive Life and my counter-corrective, The Truth about the Truth about Primitive Life). For a thorough overview of how little hunter-gatherers work, and what kind of work they do, see e.g. R. L. Kelly, The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers. Note also this conclusion in the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunters and Gatherers:

‘The most important challenges to economic orthodoxy that come from the descriptions of life in hunter-gatherer societies are that (1) the economic notion of scarcity is a social construct, not an inherent property of human existence, (2) the separation of work from social life is not a necessary characteristic of economic production, (3) the linking of individual well-being to individual production is not a necessary characteristic of economic organization, (4) selfishness and acquisitiveness are aspects of human nature, but not necessarily the dominant ones, and (5) inequality based on class and gender is not a necessary characteristic of human society’.

Not that this means pre-conquest foragers did not plan; far from it—some of their living strategies required as much forethought and long-term coordination as civilised design—but that these plans were not predicated on a stingy universe.

Foreign aid means export promotion. Aid money must be spent on goods and services from the donor nations, which impoverishes local farmers. Essentially a more sophisticated forms of classic, scarcity-creating, colonialism.

During the later years of feudalism, the members of the two leading orders—the ecclesiastical and the military—who had long exercised conditional usufructuary rights over the territories that they were responsible for protecting, gradually acquired fee ownership rights over these tracts as a result of a new legal principle: the concept of real property that was both alienable and subject to conveyance by testamentary bequest.

The landowner not only had the right to convey his land by testamentary bequest or to sell it, but also to expel those who inhabit it, divide it into separate parcels for sale and to privatize the commons.

Michel Bounan, The Mad History of the World.