Another rucksack of bibelots and whim-whams.

The Death of the Soul

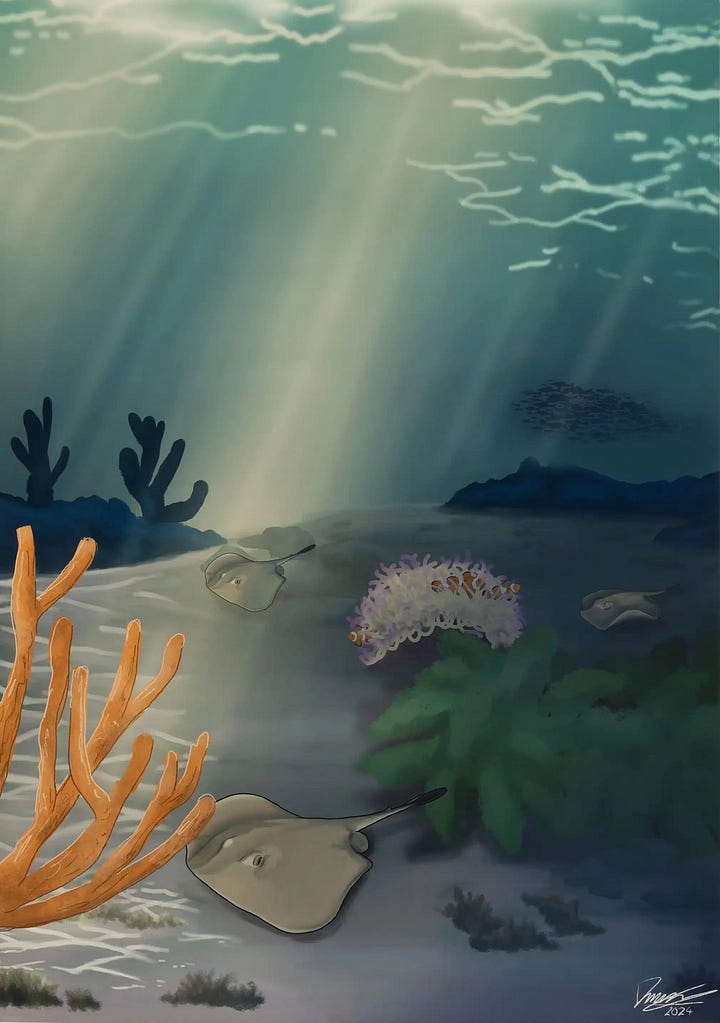

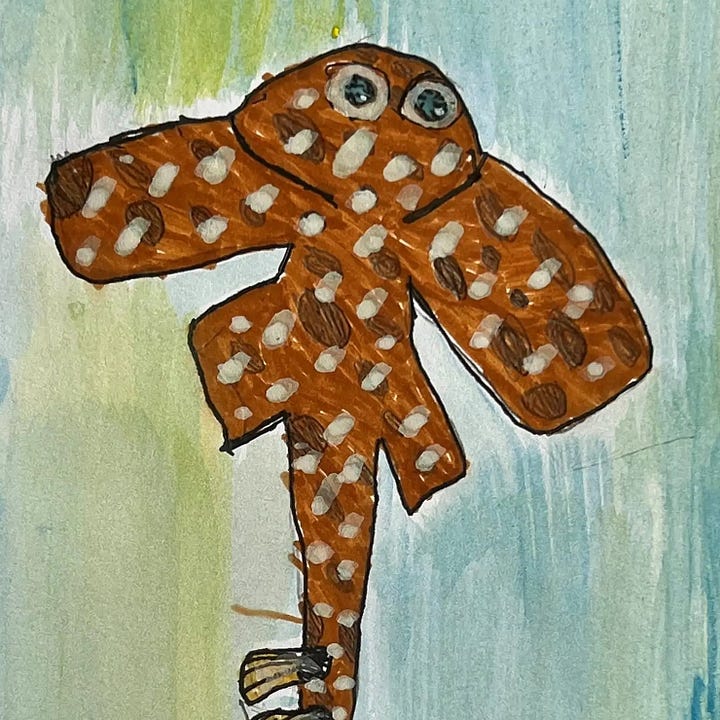

The Guardian published a harrowing account of psychological ruin the other day. Australian children under ten were invited to paint pictures of their favourite sea creature which famous artists then ‘responded to’.

Behold, the death of the soul…

It reminded me of the following story from Keith Johnstone’s Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre. It’s a bit long, but worth it…

I felt crippled, and ‘unfit’ for life, so I decided to become a teacher.1 I wanted more time to sort myself out, and I was convinced that the training college would teach me to speak clearly, and to stand naturally, and to be confident, and how to improve my teaching skills. Common sense assured me of this, but I was quite wrong. It was only by luck that I had a brilliant art teacher called Anthony Stirling, and then all my work stemmed from his example. It wasn’t so much what he taught, as what he did. For the first time in my life I was in the hands of a great teacher.

I’ll describe the first lesson he gave us, which was unforgettable and completely disorientating.

He treated us like a class of eight-year-olds, which I didn’t like, but which I thought I understood—‘He’s letting us know what it feels like to be on the receiving end,’ I thought.

He made us mix up a thick ‘jammy’ black paint and asked us to imagine a clown on a one wheeled bicycle who pedals through the paint, and on to our sheets of paper. ‘Don’t paint the clown,’ he said, ‘paint the mark he leaves on your paper!’

I was wanting to demonstrate my skill, because I’d always been ‘good at art’, and I wanted him to know that I was a worthy student. This exercise annoyed me because how could I demonstrate my skill? I could paint the clown, but who cared about the tyre-marks?

‘He cycles on and off your paper,’ said Stirling, ‘and he does all sorts of tricks, so the lines he leaves on your paper are very interesting …’

Everyone’s paper was covered with a mess of black lines—except mine, since I’d tried to be original by mixing up a blue. Stirling was scathing about my inability to mix up a black, which irritated me.

Then he asked us to put colours in all the shapes the clown had made.

‘What kind of colours?’

‘Any colours.’

‘Yeah … but … er … we don’t know what colours to choose.’ ‘Nice colours, nasty colours, whatever you like.’

We decided to humour him. When my paper was coloured I found that the blue had disappeared, so I repainted the outlines black.

‘Johnstone’s found the value of a strong outline,’ said Stirling, which really annoyed me. I could see that everyone’s paper was getting into a soggy mess, and that mine was no worse than anybody else’s—but no better.

‘Put patterns on all the colours,’ said Stirling. The man seemed to be an idiot. Was he teasing us?

‘What sort of patterns?’

‘Any patterns.’

We couldn’t seem to start. There were about ten of us, all strangers to each other, and in the hands of this madman.

‘We don’t know what to do.’

‘Surely it’s easy to think of patterns.’

We wanted to get it right. ‘What sort of patterns do you want?’

‘It’s up to you.’ He had to explain patiently to us that it really was our choice. I remember him asking us to think of our shapes as fields seen from the air if that helped, which it didn’t. Somehow we finished the exercises, and wandered around looking at our daubs rather glumly, but Stirling seemed quite unperturbed. He went to a cupboard and took out armfuls of paintings and spread them around the floor, and it was the same exercise done by other students. The colours were so beautiful, and the patterns were so inventive—clearly they had been done by some advanced class. ‘What a great idea,’ I thought, ‘making us screw up in this way, and then letting us realise that there was something that we could learn, since the advanced students were so much better!’ Maybe I exaggerate when I remember how beautiful the paintings were, but I was seeing them immediately after my failure. Then I noticed that these little masterpieces were signed in very scrawly writing. ‘Wait a minute,’ I said, ‘these are by young children!’ They were all by eight-year-olds! It was just an exercise to encourage them to use the whole area of the paper, but they’d done it with such love and taste and care and sensitivity. I was speechless. Something happened to me in that moment from which I have never recovered. It was the final confirmation that my education had been a destructive process.