I’ve dealt with specific objections to my work in the books and essays themselves, but there remain certain general complaints which tend to come up again and again, so a few words of explanation might be useful to anyone who feels confused, insulted, annoyed, or middle class. It’s fairly long, so feel free to just skip to questions you’ve asked yourself or to the ones you are interested in my bitter, angry, snobbish and dismissive responses to.

1. Refusal to [honestly] engage

‘Justification’ has an unnecessarily bad reputation today, largely because of the reign of postmodernism which scorns explanation, argument and defence of one’s ideas—‘ghosting’ is the order of the decadent day. But although I believe one should, to some extent, justify what one says, or at the very least take responsibility for it,1 I am, first of all, a little tired of repeating myself, which is one reason why I reference my other work so often. Some people (and I’m including professional editors here) seem to think that a single essay should contain everything, explain everything. Secondly, I have nothing to say to people who fundamentally disagree with me. Who does? In such cases, as we all know, argument is all but pointless. Occasionally, for the sport of it, I do engage, but if I get a strong whiff of foundational discord2 I tend to withdraw pretty quickly these days, if I reply at all; hence, for some, ‘refusal to engage’.

2. You’re saying…

Am I?

Usually I’m not. As I criticise so much of the world, I expect anger and critical counter-blasts, and I certainly get them.3 But that’s fine. Such criticisms have, as I say, been answered in my work—if you pay attention, which is difficult when the self feels threatened. The self feels it is under attack long before it knows it is, an agitation which causes the attention to skid over a text looking for something, anything, it can grab onto as a justifying reason to abandon the unpleasant experience. Most of the objections here rise to the attention for this basic reason, but if an objection cannot be found, one will be invented in the form of an assumption. This inevitably takes the form of a sentence that begins with ‘It feels like you are saying…’4 or, more simply, of putting words into my mouth. This is why much of my response to criticism amounts to little more than ‘I didn’t say that’, ‘can you show me where I said that?’ and so on; or, again, saying nothing; because, after all, what can you say to someone who says something like, ‘It feels like you’re a fascist’ or ‘it feels like you’re dead inside’? ‘No, I’m not’?

3. I Love x but Hate y…

‘I love what you say about religion, but what you say about mental health is ridiculous’, ‘Some of your ideas are brilliant, but sheesh the gender stuff’, ‘I grok your fun stuff but the philosophy is sooo boring’, ‘Your politics is great, but oh Lord your sense of humour is infantile’, ‘Great, but your critique of socialism is wide of the mark[s],’ and so on.

What can I say? Just stick to the stuff you like, I suppose, although I’m usually a bit suspicious if someone picks one thing out for special treatment (‘some things you say really resonate’) but then take other parts as cynical or abusive tommyrot (‘you’re just a dickhead’). Many readers have a tendency to agree with everything I say,5 right up to the point it touches on their class or their job (particularly professional jobs; mindworker, doctor, ahhtist…) or their hobbies, or their addictions, or their clubs, or their teams. Then suddenly, almost magically, it’s oversimplified, angry, purist, puritanical…

Another way of making the above two complaints is;

4. You make some good points, but…

Criticism usually zealously focuses on two or three secondary details and misses the main or the overall argument. I’m quite happy to hear of these secondary details, but if a critic ignores the central point they are unlikely to grasp even supporting details in context.

But, in any case, what about those good points, hm? I also find it a bit suspicious, not to mention ungrateful, when someone eats their way through a three-course meal I’ve prepared and then spends half an hour complaining about an undercooked pea.

And a third version of ‘I love x but hate y’ is;

5. I enjoyed your earlier stuff but…

Putting aside that ‘early stuff’ usually appears to mean things I wrote allll of five years ago, it turns out many who enjoyed my critique of the entire system when that appeared ‘didn’t enjoy’ my opposition to that same system’s unnecessary lockdowns. Also, a few atheists, leftists, Marxists, feminists, technostans or adherents to ideologies that I hadn’t got round to criticising in my earlier work got a bit peeved when I wrote negatively of them.

6. Full of yourself / pompous / snob / talk down to people

People who are not really sure of what’s good and true in life, can’t do anything to a very high level or don’t really enjoy their lives, usually have a low opinion of themselves, and sometimes even hate themselves, which is accompanied by a kind of background resentment to—and therefore the feeling of being patronised by—someone who does not, even when they’re not even being talked to, let alone talked down to. Not that such people are prepared to admit any of this, because self-hatred is invariably unconscious and so shielded from view by aggressively self-conscious pride6 which will think and talk of nothing but its self and then instantly accuse someone of overweening arrogance who takes responsibility for something nobler than me, me, me, me, me.

I’ve explained how snobbery became split from philistinism, and why both accusations are used against panjective quality. Here I’ll just say that love of our cultural tradition and my conviction that we must defend it against the postmodern onslaught of unmeaning—not to mention my disgust at the artistic wasteland we now inhabit—certainly doesn’t mean that I look down on popular songs and films. My work is full of praise for high quality working class art and culture. Purveyors and addicts of spiritless mass entertainment have been defending themselves against quality with accusations of snobbery for centuries.

The truth is not convincing.

7. Negative / too interested in provoking people / angry

I do find the outrage of some people quite entertaining and I evidently enjoy writing provocatively about lies and myths; but annoying people has not been a guiding motive of mine for a long time and I’m not interested in futile intellectual contention. Aggression is a degrading burden on the spirit and the corresponding anger it incites in others ranges from extremely inconvenient to horribly unpleasant.

I certainly feel passionate ire and outrage, from time to time — don’t you? — but this, a matter of necessity, is radically different to anger.7 Again, if you are annoyed (or passionless), they appear to be the same, as anger, like all negative emotions, always seeks to project itself onto others. And just as certain unhappy people look for violence and contention in nature, find it, and then declare the whole universe is a battlefield, so some readers hit on my provocative comments and declare that I am aggressive, angry, violent and so on.8

In any case, what I am interested in—amongst many other things—is an ‘apophatic’ approach to non-fiction writing, meaning the expression of truth through presenting what it is not; a kind of ‘last man standing’ argument (in Hindu philosophy this is expressed as ‘neti neti’, or ‘not that, not that’). This looks terribly negative—not to mention obtuse—to those unable to see the truth when the stone has been lifted from it.

8. ‘More radical than thou’ / puritanical / sectarian

Radical refers to getting to the root of the matter and puritanical refers to purity. I’m not advocating an unattainable [collective or personal] state, nor am I policing those who are not interested in radical change, nor am I congratulating myself on being better than anyone else. I’m saying that where I come from trees are well-rooted in the soil (are ‘radical’) and the water tastes good (is ‘pure’). Again, if that makes you feel guilty or annoyed for faffing around in the branches or drinking sewage, that’s your business.9

Another version of ‘sectarian / puritanical’ is;

9. Carping / bitterness / can’t stop moaning

This is a version of ‘you seem to be saying…’ because only someone who is not paying attention to my work can think I am a dour, humourless, goblin. People who can’t tell the difference between bitter complaint and impersonal criticism are usually being criticised—a criticism which swells in size to squash everything else worth paying attention to. (And if the self is good at nothing else, it is a genius at detecting ideological threat long before it arrives.)

As for ‘bitter’, this is usually from, or a reference to, people richer or more famous than I am, the implication being that I am jealous of their success.10 That’s why I criticise them. It can’t be because the hollow cowardice of the middle-class sickens me or that I am outraged at the scorched cultural nowhere that intellectual charlatans implicitly accept and benefit from, because this kind of outrage has its source in an actual wrong.

The goodies and the baddies only ever team up to attack the paradoxies.

10. Hypocritical / criticise industrial tech, yet using a computer

It is hypocritical to say that ‘it is wrong to eat refined food’ and then to eat refined food. It is not hypocritical to say that ‘it is unhealthy to eat refined food,’ and occasionally to do so. It is hypocritical to say that ‘it is wrong to eat refined food’ and then to promote yourself as an ultrapure healthy-eating guru. It is not hypocritical to say that ‘it is wrong to eat refined food’ and to live in a prison where only refined food is served. Once, in other words, you remove context from a critical statement it is all too easy to swat it away as hypocrisy.11

So yes, I criticise civilisation, and, oh dear, here I am in a civilised household. I’ve also been to the dentist, worked for an oil company, worn clothes made in a sweatshop and eaten a factory chicken. What this common objection misses, apart from the obvious fact that there is no escape from civilisation, is that I am criticising the whole system, not any particular part of if. I like my nice computer and my electric piano and my beautiful boots (hand-made, but also a product of the system). I am not enslaved and degraded by these isolated by things, but by the whole system, which separates me from my own life and then forces me to buy it back, piecemeal, in degraded, reified things.

11. It’s wrong to charge money / cultural theft / censorship

How can I be responsible for you not liking my work enough to pay for it? Unless of course you do like my work enough to pay for it but feel I should give it away for free? That would be even stranger though. Presumably you don’t think your local baker, tailor or electrician should live on air?

I get a few emails complaining about this. When I ask why we should pay for the root and stem of culture, but not the flower of it, either the line goes dead or a grimly utilitarian justification is offered along the lines that cultural products such as mine are dispensable and ‘therefore’ should be offered for free.12

12. Too many value judgements / where’s your argument?

Modern non-fiction, particularly in English, usually begins with some meandering anecdote, followed by a load of facts (or quotes) from the last book the author read and concludes with some kind of vague and limited platitude, the whole thing revolving around I-me-mine. My approach is usually to begin with an impersonal value judgement—e.g. modern literature is intellectual polystyrene or postmodernism is a literal nightmare—and then explain the nature of whatever it is I’m looking at, how it came to be, what the consequences are and so on. What this means is that people who share the initial assertions are encouraged and interested, while those who don’t, complain that it’s all weightless and confused and saying nothing. And that’s as it should be.13

13. Verbose / word salad

This one comes a) from people who are genuinely thick, and do not have the attention span required to get through a long(ish) sentence, or lazy, and can’t be bothered to pick up a dictionary, or b) from people who are intelligent and literate but cannot accept any expression of rationally-elusive enigma and automatically confuse it for gobbledygook, or c) from intelligent people, possibly without much book-learning, who are not in the habit of reading difficult stuff and get annoyed at those things I write which require a bit of effort. I am completely sympathetic, even apologetic, to this latter group, and can only point them to the easier and lighter stuff, which there is lots of. The first two groups should go elsewhere.

Likewise;

14. Poor style / badly written

When I inspect this claim, I usually find that it’s because someone cannot engage with what I’ve said, so automatically takes the safely unprovable ground of how I’ve said it. Very often when I try to pinpoint the claim that what I’ve written is stylistically poor, with an example, it evaporates.

I have also been accused more than a couple of times of writing ‘run on’ sentences. What these critics appear to mean is long sentences, a ridiculous charge for anyone who has read any great author born before Hemingway.14

Although of course, as the Japanese say, ‘even the monkey falls’.

Likewise;

15. Too difficult

As with some foods, some sections of my work are a little difficult to masticate, particularly, as I’ve said, for readers unused to fibrous matter. I believe that no idea is so ‘deep’ that it cannot be explained in the simplest manner, which is why I detest the shallow, obscurantist work of writers like Martin Heidegger, Jacques Lacan and Slavoj Žižek, and why even some of my heroes—Kierkegaard, Adorno and Illich—should be taken to task for their wilful bombast, but I also believe that to reach some heights the reader has to burn a few calories.15

16. Male

I am a man. What do you expect?

I sometimes get the accusation that I disparage women too, which always ends up meaning either that I disparage the modern ‘identity’ of insane women or that I disparage one woman, the reader, who is, in order to score a point, temporarily taking on the messianic role of all women.

Talking of which…

17. Gender essentialism

Guilty. Fingernails have essence, chord structures have essence, boilers and stoves have essence, as do mice and guinea pigs. The part has essence, the whole has essence—everything has essence, even numbers. Why should men and women be different? They’re not. The idea that they are, that they are hollow, interchangeable factoids capable of being shifted around like binary digits on a flip-flop circuit, is an incoherent and boring falsehood.

18. Repetitive / predictable / overly long

I work hard not to repeat myself, but everyone who covers a lot of ground inevitably does so. It’s almost impossible for different works from the same author not to overlap somewhere.

Also, one or two things can’t be said enough.

As for waffle, there’s none of that, but lacking an editor, I do occasionally let cuttable sentences and paragraphs slip into my work. Sorry about that.

19. It won’t convince many people

The truth is not convincing.16

20. Sweeping generalisations

Everyone makes generalisations.17 Language itself is a generalisation. Of course there are exceptions, which I allude to with liberal use of ‘tends to’ and ‘that’s not to say’ and so on. I ignore objections along the lines of ‘what you are saying is not exactly / technically / literally correct’ for the same reason my wife does.18

21. Plagiarism / unoriginal / basically a synthesis / heard it all before

Anyone wishing to focus on my sources wouldn’t have a hard time. It’s all there. My analysis of technology is in debt to Ellul and Mumford, my critique of mental illness is heavily dependent on that of Szasz, my critique of professionalism is partly Illichean, my metaphysics partly Schopenhauerian and what I have to say about men and women would have been much less interesting without D.H. Lawrence, Barry Long and even, once furious racism and misogyny has been deleted from the good observations they made, Nietzsche and Weininger.

Imagine though what torture it would be to read a book which was completely original.19 A good portion of original work is and has to be unoriginal, even dull, which critics, particularly widely read Dereks and Richards, focus on in an attempt to pat down the genuinely new. They do this because the original is, for most people, invisible until it has been copied a hundred times, and they have to do this because they have no idea what originality is or where it comes from. This is why second-rate minds, particularly critics, so often tell us that originality doesn’t really exist, or that there are only really ‘seven plots’ or that this or that great artist was really a magpie. Unoriginal minds can no more detect originality than a Geiger counter can detect good luck.

The freer you become, the more unique you become.

22. Offensive!

If a criticism is trenchant enough, the criticised can pull the harassment card.20 It’s helpful if the critic gets angry, but the politest criticism can be branded a form of abuse. Those in power who can call on historical wrongs to justify their outrage—powerful women, homosexuals and black people, for example—are most keen on this form of objection, for if a Jewish professional, for example, is being criticised, for anything, the critic must be an anti-semite.

While many mediocre writers fear ‘offending’ the woke brigade, and will not go near the subjects of gender, race, religion, disability and so on, many others impose subtler but equally gutless constraints on themselves in order to protect their brand, or their follow-count. They begin by writing on certain themes, attacking certain targets, they build up an audience comfortable with those themes and targets, and then, enjoying a little power and attention, they fear to stray far beyond the boundaries they’ve set up for themselves.21

Another version of ‘offensive’ is; ‘far right / far left / sexist / ableist, etc.’ If you are, by definition, on the side of the goodies, then any criticism must be, eo ipso, coming from that of the baddies. A critique of capitalism can only be a communist plot, disgust at communism has to be right-wing ideologising, inherent limits of rationalism must be relativist hot-air, criticism of postmodernism must be rationalist fascism and so on. Those who refuse both the left and the right cheeks of ego’s fat arse tend to get sat on by both. The goodies and the baddies only ever team up to attack the paradoxies.

23. Define ‘civilisation’, ‘collapse’, ‘technology’, ‘woke’…

…and so on. Apart from the fact that I probably can and I probably have, and apart from the fact that providing a definition of a term doesn’t actually explain it, it’s unnecessary. Let’s say you’re against ‘fascism’ or ‘capitalism’ or ‘superstition’, even if you can define these things — which is unlikely — who cares? We know what you mean by these words.

24. Misunderstand Marx, Hegel, Kant, etc.

It’s always possible I’ve made a mistake or missed something in work I critique, or dismiss, particularly with the Big Names; but my approach to all authors, before I get to work on a text, starts with a felt intuition, an unjudging reading of their stylistic physiognomy, and a feeling out of what they are saying. I do this with everyone (everyone does this with everyone), and, as long as I’m paying the right kind of attention, it is, even with misunderstandings, infallible, even if I get the details wrong which, not being a computer, certainly does happen.22

25. Your supporters…

Yes? Have weird opinions? Can’t use apostrophes? Eat children? This is the ‘weak man’ fallacy. Rather than addressing a criticism one looks for its stupidest or most perverse proponent who, because all truths attract fools and lunatics, is soon found. I’ve done my best to rid myself of such people,23 but one can only do so much.

26. Prove it!

This feeble objection is for any criticism which addresses truth, morality and beauty. It is employed by adherents of objectivist science (aka scientism) and relativist art (aka postmodernism) to deal with accusations of ugliness, evil and self-interest; which is to say lack of quality. Because quality is neither, ultimately, a caused fact in the objective world nor is it a subjective whim, any criticism which takes it into account can be easily dealt with by either asking the critic to locate it in the objective world or, conversely, by asserting that it is ‘just your opinion’.

27. What are your qualifications?

I have none and need none to talk about quality (morality, beauty, truth), neither does anyone else. The counterpart to this criticism is the view that professionals are qualified to make moral decisions; an opinion held by professionals, and their masochistic dependents. Surely I don’t need to explain the ethical horror that this leads to?

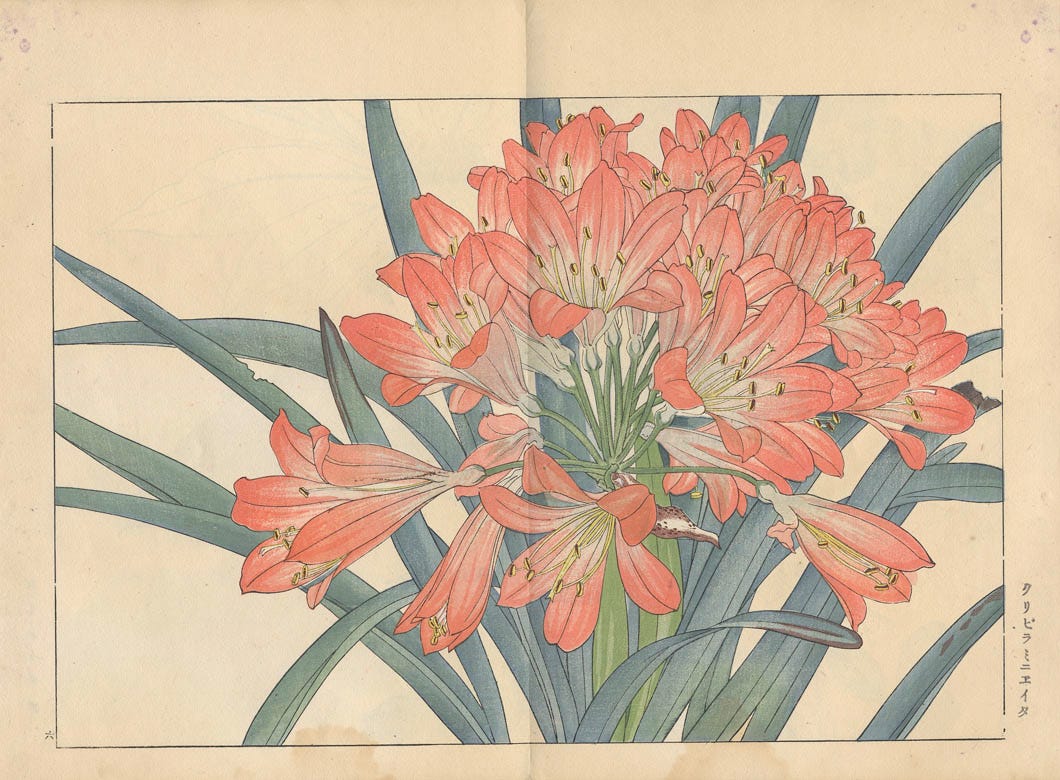

28. How can you be an anarchist when…

If you take any of the meanings of ‘anarchism’ which I explicitly and carefully repudiate to be ‘the’ meaning of that word—if, in short, you run, like a child, to the dictionary24 to settle an argument—then no, I’m not an anarchist. The thing is though, about anarchism, is that it strives to get at the essence of humanity, or the human spirit. That essence, if allowed to grow freely, manifests in an infinity of particular forms, ‘unique flowers’.25 It stands to reason therefore that it is going to manifest the widest possible variety of forms, from Jesus of Nazareth to Alan Moore, from Chuang Tzu to William Blake, from primal societies to informal shanties; most of which do not even consider themselves ‘anarchist’, nor need they. It is those forms of anarchism which seek to dilute this variety by leaving the essence unexamined, and by ignoring the means by which it is corrupted by democratic-socialist groupthink, by industrial technology, by professionalism and by the human ego, which I reject.

Some say that we need a different word to ‘anarchism’ as it has been perverted by ‘edgelords’ and socialists masquerading as anarchists.26 On the one hand I disagree — if we had to do that for every corrupted word we’d be unable to speak at all — but there is still some sense to the objection, which is why I also use ‘primalism’. This term also encompasses the essence of the pre-civilised approach to life; not, obviously, the formal facts of their lives, which are impossibly varied, and cannot be emulated anyway, but what they have in common with each other and with the best of us; soft-conscious sensitivity, refusal of constraint, cheerfulness under strain, and so on.27

29. CIA, Narc, controlled opposition, illuminati…

I’ve been accused of all these; and quite right too. It’s well known, after all, that The Man has a very lax entry policy. All you have to do is write a book or an article with thirty-three chapters, and you’re in.

30. Contradictory

Self takes the mystery from paradox and calls it contradiction.

31. Why do you only attack the left?

I don’t. I criticise both the left and the right. The majority of 33 Myths of the System, for example, criticises capitalism; or, more accurately, the capitalist wing of the system. I do emphasise the problems of leftism however because, as Ted Kaczynski put it, ‘the political left is technological society’s first line of defence against revolution’—amounting to ‘a kind of fire extinguisher that souses and quenches any nascent revolutionary movement’ and because the ideology of the left is so much more insidious than that of the right. It doesn’t require much intelligence to see why it is wrong for a handful of people to own the whole planet, but to grasp why democracy is inherently coercive, why the mass is irredeemably unconscious, why communism leads to technocratic slavery or why professional power—particularly power over language—deprives ordinary people of their own experience, takes a little more insight.

32. Do you have children?

I am a child—is that any good to you?

Gotta laugh though haven’t you? Apparently you can only make meaningful comments about life if you’re terrified about losing your job and terrified about the future of creatures who are growing up hating you for it. Not that I’m down on having kids and, actually, I miss them terribly. Those who do have them should spread them around a bit more I think.

33. Why don’t you offer solutions?

The only solution people who are free ever need is the truth of what is. They hear the truth and are inspired to act on it in their own way. This is why the freer you become, the more unique you become.

I also believe that one should invite criticism, go looking for it, particularly if you are [young and] unsure of your work, which, like the body, can only get strong under the harshest conditions, but that’s another matter.

Or sheer pointlessness.

Although, as I’m not famous enough to be a serious threat to the system, a kind of huffy silence is more common.

Daniel Pinchbeck, who once told me I should accept his opinions because they’ve ‘profoundly influenced Sting’, said my work seems ‘cowardly’, ‘toxic’, ‘arrogant’, ‘bitter’ and ‘inhumane’. No details.

Or, with particularly stupid dissidents, just be entertained by it. I’ve met a few people who, oh my God love my work, but when I ask them what exactly they like about it, or what questions they have, they start to wave their hands around a lot.

Quality, in other words, is irritating to those who cannot produce it. As Goethe wrote, people ‘prefer to be surrounded by mediocrity because it leaves [them] in peace’, which is why they all but demand a kind of apologetic, cap-doffing ‘humility’ from those who embody or produce quality. ‘Yes,’ is the message here, ‘you may do good even great things, but please do your best to convince me that my own lack of quality is, actually, equally valid.’ Schopenhauer was, as usual, more forthright; ‘For what is modesty but hypocritical humility, by means of which, in a world swelling with vile envy, a man seeks to beg pardon for his excellences and merits from those who have none? For whoever attributes no merit to himself because he really has none is not modest, but merely honest.’

I have noticed that the most furiously conceited people on earth, around whom the whole universe revolves, who have zero insight into other creatures, other humans, other realities, who are unable to listen with gentle attention, without the filter of their opinions interrupting, who are literally full of themselves, very often it is they who come across as the nicest, friendliest and most humble souls on Earth, while, conversely (although conspicuously strutting cock-brains are an obvious counter-example) there are more than a few people out there with quite ludicrous levels of self-confidence, who make preposterously firm judgements, and who have, in truth, the softest, most sensitive and, in the deepest sense, most generous hearts. In the end, it is as the man said, it is not virtue that is rewarded in this world, but the display of it.

One kind of anger is natural. What is unnatural is struggling to control it or holding up an ideal of pacifism, which nobody can achieve. Many members of the nice middle class worship some kind of pacifism and look down on anger and violence as bestial lack of control, while fairly boiling with suppressed rage (belied by their armoured deadness) because of it. Anger, in short, is to ire what fooling is to clowning, or seduction is to creeping, or sorrow is to depression. The litmus test is how someone reacts to being challenged. The intelligence, soundness or quality of what someone has to say is inversely proportional to how violent, nasty or evasively devious they are when reasonably critiqued.

Jonathan Cook, who says he cannot write meaningfully about the truth, told me that my failure to amass more readers and convince others is due to ‘rage’, ‘anger’, ‘spite’, ‘childishness’ and, my favourite, a desire to ‘spread terror’.

That someone is passionately critical of certain things doesn’t mean that he is therefore telling others what to do. This is one of the most pernicious and common logical fallacies that can be made, the leap from ‘is’ to ‘ought’. Usually this takes the form of a jump from ‘x is unpleasant’ to ‘therefore we ought to stamp x out’, or from ‘x is pleasant’ to ‘therefore we should have more of it’.

The stupid assumption, for example, that because I criticise, say, video games, or civilisation, I am therefore laying down a load of laws, and puritanically ‘banning’ Pac-Man or saying that we ‘therefore’ ought to exterminate seven billion people is usually made because strawmen are easier to confront than the argument itself. The Guardian’s favourite anarchist, David Graeber, once told me I believe that ‘99.9% of the of the Earth’s population should die so [you and your] white buddies can go hanging out in the trees.’ Noam Chomsky also informed me that I am a mass murderer on a global scale.

Paul Kingsnorth, who correctly describes his own work as meaningless, once asked me; ‘what has ever come from your pen but snark, bitterness, Manichean division?’

This has a technical name, Tu Quoque, which I get a lot of. What about you? What about you? What about you?

I also get people congratulating themselves that they paid for one of my books. Imagine not just asking your local baker for free bread because you bought a loaf last week, but actually expecting him to be somehow impressed.

I understand that high art is a different order of ‘thing’ to bread, of course, and I am against DRM, and I also accept file-sharing and illegal downloads — which I have engaged in. There’s nothing wrong, for example, in taking the work of dead artists.

My point is that I work by writing in a world that requires money to live and so it’s obviously not wrong to ask for money for that work, particularly when asking for payment keeps out people who don’t like it enough to fork up.

It’s one of the great, justifying lies of the ‘spiritual’ seeker (like ‘wise people don’t know they’re wise’) that the truth in the world is free. It’s not free. You pay for it — in pain, in effort, in service or in money.

That said, I am interested in backing up all these ‘assertions’, or grounding them, and have written a complete philosophy to do so.

Here’s an example, from Milton. Count how many ‘run on’ sentences are here. Not that I can reach the heights of Milton’s inimitable eloquence, and not that I am guiltless of writing actual run-on sentences, but I wonder how many people who complain of my bloated style could read this comfortably…

In the whole life and estate of man the first duty is to be grateful to God and mindful of his blessings, and to offer particular and solemn thanks without delay when his benefits have exceeded hope and prayer. Now, on the very threshold of my speech, I see three most weighty reasons for my discharge of this duty. First that I was born at a time in the history of my country when her citizens, with preeminent virtue and a nobility and steadfastness surpassing all the glory of their ancestors, invoked the Lord, followed his manifest guidance, and after accomplishing the most heroic and exemplary achievements since the foundation of the world, freed the state from grievous tyranny and the church from unworthy servitude. Secondly, when a multitude had sprung up which in the wonted manner of a mob venomously attacked these noble achievements, and when one man above all, swollen and complacent with his empty grammarian’s conceit and the esteem of his confederates, had in a book of unparalleled baseness attacked us and wickedly assumed the defense of all tyrants, it was I and no other who was deemed equal to a foe of such repute and to the task of speaking on so great a theme, and who received from the very liberators of my country this role, which was offered spontaneously with universal consent, the task of publicly defending (if anyone ever did) the cause of the English people and thus of Liberty herself.

I should mention here again my most important book, Self and Unself, the first few sections of which, are quite hard going for some people. It’s probably the clearest book of philosophy you’re ever going to read, but it is a little more abstract than the rest of my work, and isn’t as light-hearted—necessarily, as I had to lay some technical, metaphysical foundations—so I understand why it ‘fell stillborn from the presses’ and alienated a few readers expecting a chatty stroll through the fields of the mind. Shame though.

I am careful to make a case and to pre-empt misunderstandings, but I have no interest in convincing anyone of the truth, because it cannot be done. (Oscar Wilde; ‘Everything must come to one out of one’s own nature. There is no use telling a person a thing he does not feel and can’t understand.’) This allows me to say what I want to say. Many will draw the wrong conclusions, but that’s just how it is.

No, friend, it’s just you I want to talk to. You’re the only person who needs to hear what I have to say, and with whom I want to speak. You’re an intelligent person, so you need good, solid arguments, and I have provided them (apart from anything else, because I take pleasure in doing so), but I’m not trying to persuade you. Ultimately, you agree or you disagree, and that’s it.

This is a sweeping generalisation.

Also, I’m not an academic specialist. What I have to say about the subjects I’ve written about comes down to what they have in common, how specialist thinkers are blind to this commonality and how this blindness obscures simple truths available to anyone. Specialists in possession of more facts, can, and should, amend the details of what I have to say when I am in error, because rational facts matter; they just don’t matter as much as what they have in common.

This is why it sometimes looks like I’m making ‘sweeping generalisations’ when I am drawing attention to something beyond details. This is something else that annoys specialists who, in order to handle the irritation, tend to withdraw to their detailed field of expertise in order to try and ‘mount me’. Even then I usually find that the facts evaporate under inspection, but in such cases I usually prefer to evaporate myself.

This is an original comment.

The term ‘gaslighting’, which conflates ‘saying something I don’t like’ with ‘making me doubt my reality’, is popular today amongst those whose sense of reality is so weak that words can damage their confidence in it.

This became all too clear during the pseudo-pandemic, when writers who knew it was all lies shit themselves because they might lose readers. But any idea that threatens a writer’s security, by going beyond what his or her readers expect or are comfortable with, provokes the same kind of fear. I know because I’ve felt it myself. This is why so many writers, some pretty big, refuse to publicly endorse my work except, and only then occasionally, in the most guarded and roundabout way.

I’m still waiting for someone to set me right on Marx though. When it was published I got a lot of huffing and puffing from people like John Steppling and C.J.Hopkins, but nothing of substance. I’m really quite happy to be shown my error there, or indeed with any fact. Not being God I often make mistakes with the pesky things.

Mostly by not censoring myself. William Blake; ‘Always be ready to speak your mind, and a base man will avoid you’. This is superb advice, but not if you’ve got a brand or a follower-count to maintain.

Owen Barfield, The Rediscovery of Meaning.

U.G. Krishnamurti.

e.g. David Graeber and Noam Chomsky.

Lots of important words are like ‘anarchism’, degraded, debased or just plain old debatable, and as with anarchism there are two choices; decamp or redefine. Take ‘love’, which means, for the most part, a sticky, possessive, personal emotion that ‘more closely resembles hatred’ (La Rochefoucauld again; ‘If we are to judge of love by its consequences, it more nearly resembles hatred than friendship.’). What is one to do, use another word, or give love back it’s pristine, impersonal coldness, its almost terrible intensity? I choose the latter.