Beyond Theory

Theories come from the mind. This is obvious enough, theories can no more be found in the world than ‘left’ and ‘right’ can, but we forget that mind conceals as much as it reveals. Mind misses quality, because it can only deal in quantity, it misses the unique, because it can only deal in the general, and it misses unity, because it divides experience into the subjects and objects, or incomplete things, of the world. This doesn’t mean that the mind literally creates things, the insane position of the solipsist, rather, as Kant and Schopenhauer demonstrated, that it creates our experience of things. This fact, demonstrably the case and essentially confirmed by modern neuroscience1 refers to a phenomenally useful activity—the human mind is literally the most useful thing in the universe—but, just as everything is a nail to a hammer, so everything is a rational object, or thing, to mind (even the self, the subject, is an object to mind).

Constrained by its own parameters, mind cannot perceive or create anything fundamentally irrational, anything mysterious or ‘non-thing-like’. It can create gibberish, but nonsense is, in principle, understandable. Flying cows and green ideas and fork-over got wow Jessop Jessop don’t meaningfully relate to anything in the world, but the mind can grasp them, albeit uncomfortably. Nonsense lies within its limits, unlike, to take Kant’s example, an absence of space, which2 cannot be imagined. What this means is that mind cannot advance knowledge in any genuinely original way, for it is unable to experience anything beyond itself, including its own origins, nor can it experience phenomena directly, qualitatively, from within, only its own representations of that quality. And what this means is that if mind is the final arbiter of reality, self is trapped in a prison of itself, which forces it into a dependency on technique, which, even though it swallows the world, can never bring the other to me, in love, and can never release me from the anxiety of being a finite being in a hostile universe.

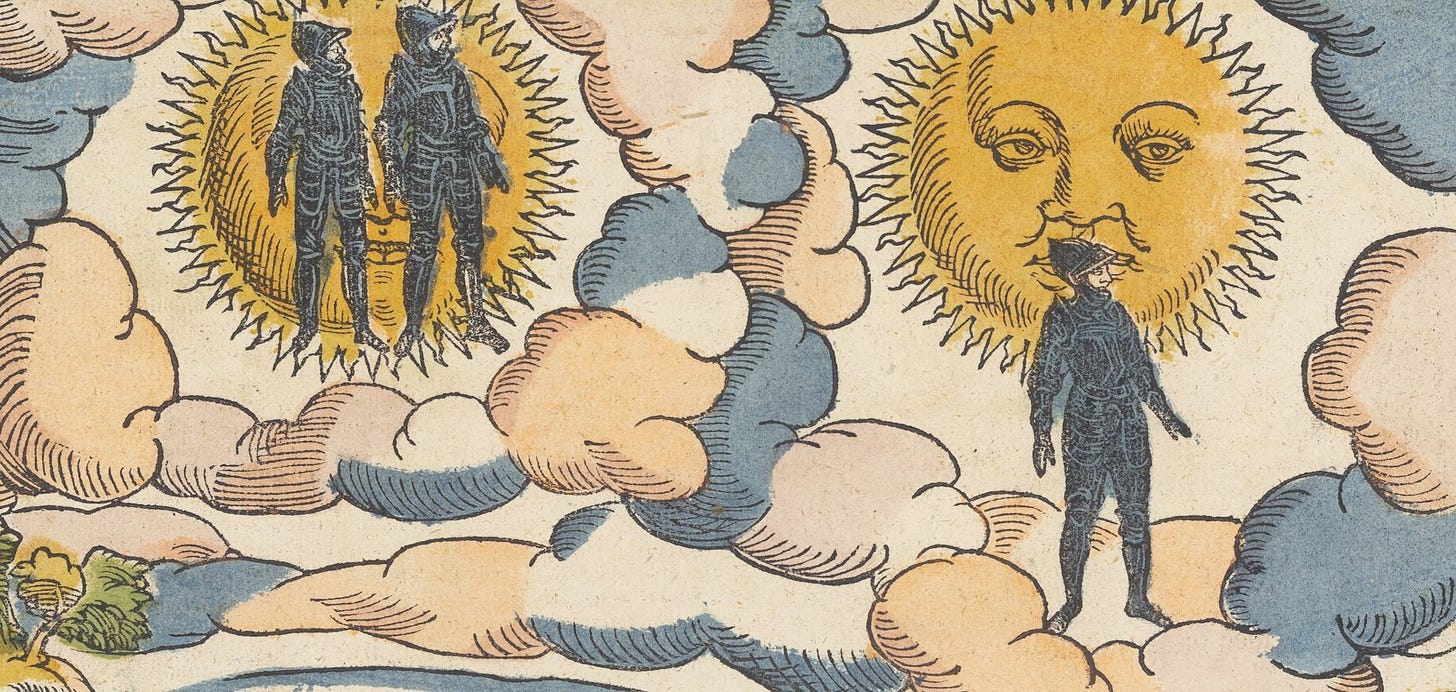

Two points need to be made before we proceed. Firstly, rational thought understands useful facts and reveals useful theories, without which we would be helpless and insane, but facts are not truth, and utility does not equal quality; distinctions which are all but impossible for the isolated rational mind to grasp. It is a fact, for example, that the sun is a hot ball of gas, just as it is a fact that two plus two equals four; but these facts, useful as they are, are not the truth. They tell us nothing about what the sun is, or what the number two is. Science doesn’t even try to tell us what things are, and nor does it have to, because abstract facts accurately represent that within nature which is factual, that which is graspable-by-mind.3 Again, only a solipsist, postmodernist, or outright liar denies the reality of facts, facts which are prodigiously useful, just as theories about those facts are useful, which is why we think about facts and make theories in the first place. This is what abstract reasoning is for. It is a tool, to grasp the graspable and split the splitable, like an axe. But just as an axe can tell us nothing about a tree—all it can do is chop it down—so rationality, in itself, cannot reveal or experience the absolute truth, only convert it into relative fact. Abstract reasoning can produce knowledge, but it cannot reveal meaning. It can tell us why something is, but not what it is. It can grasp quantity but cannot even conceive of quality. It can work out whether someone is guilty, but it has no notion of right or wrong (outside of mere utility) and, therefore, can never make a moral choice.

The second point is this, and it is most important. There is no experiment or argument that can verify the claim that mind conceals more than it reveals, or that scientific study can never reveal what lies beyond its own limits. Science, in other words, cannot confirm its own validity. It is a category error to imagine that it can, that science can verify its own ability to apprehend reality. It can no more do so than an eye can see itself, or a torch can show us what darkness is. And just as a mode of experience that does not require a torch is necessary to experience darkness, so we need to abandon rational thought—or rather put it aside (for only the stupid and the insane never think rationally)—to ascertain the truth-value of statements which appeal to non-rational experience without reflexively ruling them all out as silliness, blind superstition, nonsensical abstraction and subjective whim.

Suggesting that to experience or even understand matters of primal importance one has to abandon rational thought is unlikely to find a warm reception amongst those whose livelihoods depend on mind; rationalist academics and technicians, who, in schools and universities around the world, do not permit serious enquiry into non-rational truths. Irrational lies are certainly entertained, everywhere, as are rational facts, and the noisy conflict between their proponents—between atheists and theists, between scientists and artists—is broadcast hither and yon; but meaningful talk of non-rational experience, such as the account you are reading, frustrates objectivists just as much as it does subjectivists, neither of whom are able to comprehend valid arguments that rest on irrational premises, and tend to dismiss them out of hand, without serious reflection. We are not talking of fairies here but, ironically enough, the very reason that rationalists appeal to, which itself rests on foundations which the mind cannot inspect. This is why any enquiry into these foundations, into, for example, the metaphorical nature of number, measurement and causality, much less the suggestion that we have known for centuries that such foundations do not even exist, are met with the same kind irritation and reflexive dismissal as talk of astrology, ESP and morphic resonances.

Faced with an attack on the [illusory] ground of reason, the committed rationalist will inevitably demand proof. He will never be satisfied that reality is not built up of facts until he has been presented with a series of facts which prove otherwise. This is like a blind man who will not be satisfied that light exists until he’s heard the sound of it. We cannot present irrational truth in a manner which satisfies rational thought, but this doesn’t mean we cannot describe the limits of such thought. We certainly can, as Hume, Kant, Schopenhauer, Wittgenstein and many others have demonstrated. The most important ideas of such thinkers, insofar as they relate to our theme—Hume’s problem of induction, Kant’s transcendental arguments, Schopenhauer’s enquiry into the limitations of representation and Wittgenstein’s critique of meaning and certainty—are unanswerable by the rational mind, but this doesn’t mean, as all these philosophers stress, that there is anything wrong with reason, an activity which is as natural to us as vision. What we are interested in here is what the eye of the mind cannot see; not an airy-fairy realm of spirit, but the unadorned reality of my own conscious experience. The truth.

But what is the truth, if not a fact? If the truth of an eclipse is not in that which caused it, or in any other fact about the sun or the moon, then what is it? If the truth of Hamlet’s ‘to be or not to be’ speech is not in the intention of Shakespeare to say this, that or the other, or in the aggregate definitions of all its words, then where is it? If the truth of my life is not in the facts of my past, in my genes or my upbringing, how on earth can I find it? The unacceptable, unbelievable truth of these things… is the thing. The truth of the matter is the experience of it, and the thing and the experience are one, before the mind abstracts the singular event of my consciousness into subjects and objects.

This incredible, outrageous simplicity of this appears confusing, complex or tautologously absurd to the mind, principally, as we have seen, because it invites the mind to step beyond itself, which is impossible. But we encounter a further problem communicating such realities in ordinary speech, particularly in English, one of the most degraded languages on earth, which unnaturally divides experience into subjects and objects (‘I am happy’, which in English is different from ‘This situation is a happy one’), obsessively divides time into a bewildering specificity of tense (‘I’ll have finished by five, but I would have started earlier if I hadn’t been talking for so long’) and demands identity between subject and predicate (‘She is stupid, he is gay’), giving us the impression that reality is so constituted. When we English speakers read a sentence that begins ‘the truth is…’ —we have to fall down on words which locate what follows either out there (in ‘the thing’, ‘phenomena’, etc.) or in here (in ‘experience’, ‘consciousness’, etc.) when in reality this distinction, useful as it is, ‘follows’ from a primal, panjective experience of oneness in which I and the other are actually, in my own direct experience, one and the same.

Thus, the foundational truth of an eclipse is the eclipse, that of the soliloquy is the soliloquy, that of my life, is my life; and all these things are no different from the I, or the apparent I, which experiences them. The phenomenal, primal simplicity of this, well understood by young children, is impossible for the mind to grasp, and is as outrageous to the rational objectivist, looking for the rational fact, as it is to the irrational subjectivist, who believes that meaning has no object, and can be personally or culturally determined. That an event in the world is the same thing as that which appears to cause it, that the meaning of a text is the same thing as the intention of its author, that the things that happen to me are the same thing as the I which experiences them; such ideas cannot be allowed into the serious business of theorising, for they upset the ultimate possibility of theory, and with it the power that the ever-theorising academic rests his whole life upon.

All theorising, like all thought, provides us with useful information about reality, while at the same time obscuring experience of the reality that theorists are hoping to understand. A good theory about emulsification is useful for the man who makes mayonnaise, and, once tested, it will help him to make better mayonnaise, but it cannot tell him what mayonnaise is, or how it tastes. No theory can. Thought is unable to experience, it can only form symbolic representations of experience. It can then reason from its symbolic premises and hypotheses, but it cannot discover them, because it cannot step outside of itself. This, the ‘problem of independent access’, is an insoluble problem in philosophy. There is no logical way for the mind to step outside itself and question its own premises, or find new hypotheses, any more than a hand can grasp itself. Just as more thought, more research, more analysis gets the scientific theorist no closer to the origin of thought, and just as analysing the words of a great poet or the notes of a great composer gets the art theorist to closer to the miracle of meaning the poem or symphony expresses, and just as approaching the problems of one’s personal life through thought gets the psychological theorist no closer to meaningfully addressing a client’s ills, so apprehending our social reality through the obsessively focused, thing-generating rational mind, gets the conspiracy theorist no closer to what is really going on in the world, or what can be done about it; for the mind can only produce facts and theories.

Beyond Conspiracy Theory

A conspiracy theory is no different to any other kind of theory. It carries the modifier ‘conspiracy’ because it directs its rational attention to the conspiracies of people in power. As with theories generally, this is a useful activity, for such people do conspire, and they seek to hide their conspiring, which those of us on the receiving end of power and privilege can and must reveal through rational analysis. Investigating the available data on the activities of our elites in an attempt to discover what they are planning is no different in principle from investigating the heavens in an attempt to predict an eclipse. In both cases facts must be gathered from reliable sources, with reliable instruments, and, as far as possible, assessed without prejudice. Testing theories logically based on these facts then gives us confidence to face the coming darkness.

So there is nothing wrong with conspiracy theories, and the slur ‘conspiracy theorist’ actually carries as much pejorative weight as ‘theorist’ does, which is to say, in itself, none. Just because elites have equated the practice with terrorism, and just because some folk, alarmed at their implications, dismiss such theories out of hand, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t use the term ‘conspiracy theorist’ in a neutral, descriptive sense, or that to do so is tactically unsound. If we had to avoid using words co-opted or degraded by others for fear of falling into their hands we’d be rendered speechless in short order.

The issue here is not the act of conspiracy theorising, or the term we use to describe the activity, but, as with any other theorising, how solid the facts are, how intelligent the reasoning is, and critically, as we have seen, how far the theory reaches beyond itself. Leftist theories, which restrict their ambit to plutocratic corporatism, or right-wing theories which direct their ire at socialist professionalism, are certainly of some use—enemies often have a lot of value to say about their respective failings—but their inability to understand the whole system, of which they are both a part, drastically limits the power of their analysis and the efficacy of their proposed solutions, which are, invariably, almost pathetically reformist.

Let’s look at two popular conspiracy theorists of our times. One on the nominal left, Noam Chomsky and one from the so-called right, Jordan Peterson. Chomsky is bitterly critical of corporate power and of states which uphold and merge into that power—particularly the USA, the UK and Israel. His exposure of the crimes of the West, and the subservient ‘mandarins’ who excuse them, is almost impossible to gainsay, with those who have attempted to do so forming a pile of intellectual corpses at his feet. Move beyond this narrow critical focus, however and he becomes vague and confused. Take as an example his ‘Propaganda Model’ expounded in his 1988 publication, co-authored with Ed-Herman, Manufacturing Consent, which describes the filters which prevent certain facts from being spoken of in the mainstream press. The model remains a lightning rod for establishment elites and their corporate employees, who frequently denounce it as a ‘conspiracy theory’ for the simple reason that it is, within its limits, a very useful idea, one that elegantly explains a great deal of factual bias in the media.

But the propaganda model, like the rest of Chomsky’s work, does not take in the entire system, nor the truth from which a more meaningful critique could emerge. Chomsky is a socialist, with all the blindspots of this notoriously bourgeois ideology; technophilia, uncritical professionalism, hyper-rationalism and so forth. His ideas take no account of the primary sources of deception, illusion and newspeak; civilisation and ego, which explains why writers with none of the pressures of the propaganda model, who are outside of corporate institutions (such as market-protected academics and ‘independent’ bloggers), who do not experience the pressures of ownership, advertising, sourcing, flak and (the most absurd of the five filters) ‘anti-communism’ can and nearly always do produce system-friendly propaganda of the most insidious and disabling kind; including of course, Chomsky himself, who, in his implicit acceptance of democracy, industrial technology and ‘Enlightenment values’ does more to uphold the system than he does to critique it.4

On the other end of the ‘political spectrum’ is Jordan Peterson, a self-described ‘traditionalist’ who supports the (‘traditional’?) state of Israel, with barely a critical word on corporatism, statism or even on authority in general, which he considers an expression of [a confusingly articulated] bio-genetic-archetypical Principle of Order which man imposes on the world. Where Chomsky directs his ire at the capitalist owners of the system, Peterson targets the socialist managers of the machine, and the philosophy of postmodernism which they more or less coherently, or consciously, embody. As with Chomsky those who take on Peterson, on his own turf so to speak, are almost invariably crushed, partly because, like Chomsky, he is eloquent and reasonably well-informed, but principally for the simple reason that, like Chomsky, within the limits of his rather narrow critique he is right; the ideologies which animates the modern identitarian left—collectivism, statism, postmodernism and so on—are indeed a pernicious form of social sickness which seek to melt both natural and unnatural distinctions down into a mindless, cultureless, characterless puree and which, in order to so, promote a fanatically censorious atmosphere of persecution which increasingly pervades our entire society.

Step beyond Peterson’s critique however, and one finds oneself with ideas which are, to the extent they are clearly expressed, pathetically superficial. Like Chomsky, Peterson supports democracy, accepts industrial technology, was silent on lockdowns and vaccine mandates,5 has nothing critical to say about the roots of civilisation and very little meaningful to say about human nature beyond a mash-up of Jungian myth analysis and Judeo-Christian psychotherapy (‘the degree to which you can manifest the logos is going to be radically associated with your functionality in human hierarchies.’) which he combines with a series of bromides such as ‘If old memories still upset you, write them down carefully and completely’ (i.e. reduce your soul to a legible, manageable artefact).

We should note here a few positive commonalities between the two theorists. Both, for example, oppose postmodernism, although for different reasons. Peterson believes it is undermining capitalist society while Chomsky believes it is undermining socialist activism. The two of them are also strongly in favour of free speech, happy to defend the right to express views they detest, and both believe that the modern world corrupts and weaken us, although neither has a very firm grasp of why and how.

Academic reformists, like Chomsky and Peterson, offer useful analysis, but this analysis is limited by their literalism, their fundamentally system-friendly outlook and by their elitism. Chomsky, for the most part, upholds the ideology of the professional management class, for whom the masses are ‘victims’, cruelly deceived by those smarter and more powerful than they are. Peterson, supporting the owners of the world machine over its managers, criticises the kind of statism which Chomsky upholds, believing that everyone is individually responsible for their lives, should stand up straight, be precise in their speech and try to make one room in their house as beautiful as possible; while, at the same time, submitting to the market and to certain forms of religious traditionalism. In both cases, the system as a whole is allowed to carry on its work, through its civilised assumptions, through the imperatives of its technology, through the mob-rule it calls ‘democracy’ and through the unhappy supermind it calls ‘human nature’, none of which receive radical critical scrutiny from either Chomsky or Peterson, or indeed from any conspiracy theorist, on the right or the left, all of whom fundamentally uphold the system.

This is why conspiracy theories, the socialist theories of the management class and the capitalist theories of the owner class, are allowed into the public realm. Penguin Random House for example, the largest book publishing corporation in the world, publish books by Noam Chomsky and Jordan Peterson. If you are excited by their ‘dangerous’ and ‘radical’ ideas, or by anything published by Penguin, or by Verso or Pluto, or that the newspapers are discussing, or that is trending on Twitter or Facebook or is receiving a great many likes or follows on Reddit or Substack, then, I put it to you that you are almost certainly championing some kind of reformism, an idea which seeks to merely modify the system we have, rather than do away with it. Such ideas are, despite much noisy complaint, encouraged by the system — which is how we all know the names Noam Chomsky and Jordan Peterson (not to mention Slavoj Žižek, Chris Hedges, Sam Harris and other tedious middle-class mediocrities)—as they make revolution a manageable affair, or a quietist irrelevance, and offer a kind of moral salve for those uncomfortable with the iniquity of their position. Step outside of the small pool of light such ideas produce however, and you find yourself in darkness.

Take, as a practical example of ‘manageable’ dissidence, the trade-union movement, which has no interest in giving workers actual power, much less real understanding of the civilised prison which confines them, only in providing employees with better management, which is to say, with sops and comforts. True, these ‘sops and comforts’ have, in the history of trade-unionism, included the lives of its members, which early capitalist institutions crushed willy-nilly, but keeping people alive is not revolutionary. Trade-unionists, like all ‘radical’ professionals, scorn the intelligence of ordinary people, their ability to organise their own lives, without professional intervention, or to judge the situation for themselves. There is no such thing as a trade unionist who seriously campaigns for an end to work, for an end to alienation, for an end to technological slavery, for the simple reason that such a campaign would put him out of pocket.

More robust than the shallow tinkering of standard leftism and rightism, and more illuminating, are those theories, much rarer, which attempt to take in a larger or deeper view of our civilised ills, and which threaten a kind of revolt which goes beyond the futile chair-shuffling of reformists and crusaders. We could call these, in distinction to conspiracy theories—either the useful kind, offered by Chomsky and Peterson, or the useless variety that people like David Icke and Alex Jones offer—institutional analysis or systemic theories6. One such theory, appearing at the tail end of lockdown era, was offered by Belgian psychologist Mattias Desmet, who, building on Hannah Arendt’s theories of totalitarian conditioning, presented, in his 2022 book The Psychology of Totalitarianism a theory of ‘mass formation’ which presented a more thorough examination of our contemporary malaise than that offered by most critics at the time.

Mass Formation, according to Desmet, comprises four conditions which lead to the kind of widespread delusion and chilling authoritarianism we saw in 2020. These conditions are; social isolation, absence of meaning, free-floating anxiety and causeless frustration. With these in place, pretty much any enemy can be presented as a ‘cause’ for our woes, which we then need to ‘unite’ to combat. For the Nazis it was the Jews. For lockdown enthusiasts it was anti-vaxxers, but it could be any scapegoat. (Only about 30% will accept the scapegoat and violently attack dissent, a small minority will rebel and a crucial 50% will suspect something is fishy but go along with the consensus for an easy life). No conspiracy theory is necessary to explain the new state of terror and confusion, nor the various repressive measures we ‘must’ employ to deal with the threat; all this arises by itself when the conditions for mass-formation are present. All that is required for leaders to do is to create or promote the form of the scapegoat, and everything will develop more or less by itself.

Desmet’s argument is flawed, first of all, by its narrow emphasis on ‘hypnosis’. Human beings are no more ‘hypnotised’ by ideology than they are controlled by propaganda or formed by education. Privileging such ideas reveals the bias of the mind, or the mind-worker, rather than the reality of the situation, which is more profoundly debilitating than the absorption of goodthink. What actually happens is that the whole self—the body, the mind, the emotions and the will—is shaped by its environment. In the machine system the self isn’t merely instructed to obey, an instruction which can simply be countered with a different, better kind of input, it is shaped into a mechanism. Where institutional thinkers such as Chomsky and Peterson attack the inputs, for they and their friends are at the input-end of the machine, genuinely radical critics critique the entire mechanism (Ivan Illich, for example, whose silence in Chomsky and Peterson’s work is deafening).

Managing inputs (i.e. indoctrination) is certainly necessary to maintain the pseudo-reality of the machine-like self, but it is the most superficial element in the subjugation of man to that reality. There is really no need to feed a machine ideology into someone who eats machine food, manufactures machine products, entertains and educates himself through a machine, lives and moves to the rhythms of a machine. Such a person, or shell of a person, can be trusted without being told what to think, without being mystically impregnated with a hypnotic suggestion. Being a thinking machine, the fearful civilian does need ideas which justify his way of life, and so these are provided, but they don’t have to be much more sophisticated than the carrots and sticks we use to train domesticated animals; because the animals are already domesticated.

Desmet goes on to claim that not just the people but leaders ‘are hypnotised by their ideology [and] by the masses.’ Again, there is some truth in this, but Desmet’s critics are right to be outraged by this whitewashing of elite agency, which brings us to another serious flaw in Desmet’s book, his complete dismissal of conspiracy theories. This is, as his leftist critics point out, a dreadful, if not immoral, error, for just as there are thing-like objects out there which, in a meaningful sense, can be said to causally affect each other, and just as we need scientific theorising to reveal these things and causes, so those we need conspiracy theorising to reveal the conspiracies of those who command and manage the machine. Working to reveal the actions and motives of those in power is, as it has always been, the means of living free of that power. Dismissing all conspiracy theories as inherently irrelevant leaves a good part of the machine intact and, what’s more, is welcomed by those who sit at the output end of it, filling their pockets as the mechanism grows in size and power. They like nothing better than the idea that their role in its operation is, at best, secondary and that they are not really responsible for the iniquity and degradation that they contribute to.

Nevertheless, Desmet is right to point out that the primary cause of our malaise is not a small group of baddies lording it over innocent victims, which cannot explain the almost unbelievable stupidity and cowardice of the masses nor the complicity of the middle-class in exploiting it, neither of which leftists are able to criticise, for the simple reason that their position as professional managers of the multitude depends on a combination of their own noble innocence (The Doctor! The Teacher! The Professor!) and the helplessness of the multitude they heroically serve. This is why leftist conspiracy theories aim all of their indignation at the ‘top one per cent’, at the owner class, and are curiously blasé about the shameful servility of the working man, the collective evil of the management class and the technological system they both maintain.

Take, as an example of mass complicity, the pseudo-pandemic of 2020-2022, when there certainly were efforts from elites to rebrand seasonal flu as a civilisation-threatening, lockdown-justifying, money-printing menace, to massively expand technocratic totalitaria and, for good measure, inject the world with experimental gene therapy, but all of this was made possible by the wilful and often sadistically enthusiastic complicity of the professional classes, along with almost unbelievable conformity from the masses, many of whom well knew that the whole thing was sham. From whence this breathtaking cowardice? Was it instilled in them by Bill Gates and the board at Blackrock? No, the very self of the modern mass-man is formed by the civilised life he leads and inspiring exceptions, of which there were many, only prove the rule. Did the masses ‘get what they asked for?’ Obviously not. But millions upon millions of them pathetically accepted lockdowns and vaccinations, just as millions of professionals actively pushed for them.

Returning to Desmet, his theory is certainly catastrophically flawed, for the reasons his leftist critics outline. It absolves the monsters who own our world and it posits an overly simplistic theory of ‘hypnotism’ to explain their power over us, one which lets the technological system off the hook. We can and must reach beyond Mass Formation, down into the depths of consciousness and out into the mysteries of nature, to understand the world we live in , but as an approximation of the systemic forces which shape the totalitarian subject, Mass Formation is more useful than leftist conspiracy theories which exclusively target the WEF and the BAP and the [very real] machinations of the super-rich and super-powerful. Those who dismiss Desmet’s and Arendt’s theory don’t like to seriously consider this, much less a more profound systemic analysis, for three reasons.

Firstly, because it would mean that they would have to think more deeply than finger-pointing. It’s difficult to untangle the knots of modernity and identify the true or complete, rather than obvious or partial causes of our ills. Conspiracy theories hold particular appeal for the functionally and culturally illiterate, for those without any real interest in profound social analysis, intellectual tradition, the causes and effects of domestication, the psychology of mass delusion or history as anything but a façade, a tissue of lies pulled over easily grasped good-guy-bad-guy stories. Arendt noted the appeal, in her time, of the ‘Protocols of the Elders of Zion’ conspiracy theory and ‘backstairs literature about the Jesuits and the Freemasons’ which, like our favoured theories, are symptoms of the postmodern belief that one can change the past at will, read anything one wants to read into it and paint the facts with whatever ‘narrative’ one fancies.

Some narratives are certainly more warranted than others however, and not all conspiracy theories are created equal. It’s certainly not the case that sober analyses of the activities of powerful globalist institutions are on the same level as ‘I believe the Freemasons are behind it all’. The elusive point is that the Machiavellian plans of the global elite are part of a system which also comprises the professional substructure beneath them, the alienated mass beneath them both, the technosphere, which envelops and penetrates us all, the civilised Leviathan that has carried all this along for the last ten millennia and the fearful, isolated ego which built and sustains this monstrosity. Singling out, as all conspiracy theorists do, a small group of baddies sitting in the cockpit, allows the whole thing to trundle along unmolested.

It is because we are imprisoned by the totality that, as Arendt also points out, very often there are no lies and tricks in totalitarian propaganda or in any other self-justifying image of the world. There’s often just no need to deceive. The ‘propaganda of totalitarian movements which precede and accompany totalitarian regimes is invariably as frank as it is mendacious.’7 Lies are crude and only used by amateurs. As Goebbels, who hated lying,8 used to say, ‘Everybody must know what the situation is.’ And even when crimes are officially concealed, they are often widely suspected, with the complicity of the servile masses and leftist intelligentsia, who are unwilling to investigate any further than is prudent. An alliance is formed between the cowardliness of the mass-man and the ‘fear porn’ of the system. The average modern is able to question propaganda, to resist orders which he knows to be ridiculous and arbitrary, to express his individuality and stand up for his integrity; he can, but he doesn’t, because he has neither individuality to express nor integrity to defend. His virtues have been colonised by his world and subsumed under his fear. He can see the lies, he knows they are lies, but he doesn’t care, or doesn’t care enough. What he cannot see, is why he doesn’t care—and why freer people than himself do resist9—because to see this he would have to rise above his lack of interest and energy, rise above himself, and this he cannot and will not do.

This is the second reason that deep systemic analysis is rejected by conspiracy theorists, because they don’t really want an alternative to the system we have. Just as the scientific theorist seeks a tidier version of The Mighty Paradigm, so the conspiracy theorist simply seeks a better-organised system, one that gives him, or his class, a position of comfort or prestige within it. The right wing theorist guns for the elites (in the name of the humble working man) and the left wing theorist speaks for the noble professional (in the name of the humble working man). They target the players—the CEOs, the corporations, the farmers, the government, the identity politicians, the Jews, the Marxists, the fascists, the New World Order, the billionaires, the technocrats or Satan—but they’re not quite so keen to attack the play, the system that furnishes them with their technology, their addictions or their prestige, or, God forbid, the whole self that is fused to it.

Which is the third, and the most profound, reason why conspiracy theories—why all theories—are more attractive than perceiving the substance of the system and the self. It is because that substance is not just made up of thought—the basis of theory—but of emotion, will and perception, and these the conspiracy theorist cannot intelligently address, because to do so he would have to take up a ‘position’ outside of the only reality his system-fused self can know. This is why any kind of meaningful reference to selflessness, for example, or enquiries into love, or truth, or beauty, are all conspicuously absent from the work of theorists, as is the reality these words refer to, which explains of the most obvious features of political writing which focuses on conspiracies, particularly leftist theorising, is its stupefying monotony.

There is much talk of ‘waking up’ in dissident literature, but it’s just that. Talk. Intellectuals, journalists and radical commentators have no interest in reaching beneath the mind, of inspiring the individual, speaking to her uniqueness or breathing life into her living, conscious experience, because they have none themselves. This dreamlike attachment to the known is reflected in a prose style that is, in the case of academic analysis, shallow, brittle and correct, a tone that is dry and cheerless, and, in the case of more ‘creative’ writers, a sense of humour that is, at best, grimly sardonic, at worst feeble. The analysis is crude, the vocabulary is repetitive, the range of subject-matter narrow and, when they reach for wit and individuality, they grasp little more than a meta-narrative that constantly refers back to the self of the author, his importance, or the minutia of his sad and beautiful (but unremarkable) life; a kind of easily digestible self-regarding chattiness. Worst of all, the whole thing gives off a reassuring sense of familiarity. The reader nods away, never really challenged, never really outraged, never really horrified, never really shaken with delight, or taken out of herself. She knows, like the author she is reading, that to grasp the root of the matter is to go underground, out of the light of her comfortable mind, and there be monsters.

Conclusion

Confined by the facts, the conspiracy theorist—like any other theorist—is unable to solve the problems he discovers in the world. He almost invariably discovers useful facts and illuminates those facts, but he cannot move beyond the restricted range of his causal theorising. Truth is a dirty word. And yet, without the truth, we are confined by the facts we seek to change. This is why, when we seriously act on the discoveries of our finest theorists, we achieve nothing; why, for example, the world we live in now, which is the result of four hundred years of brilliant theorising and profoundly useful fact gathering, is not fit for human habitation. It wouldn’t matter if we perfected our theories, or if we eradicated all the evils posited by them, it wouldn’t matter if we realised the dreams of the Enlightenment and built a socialist paradise, and it wouldn’t matter if the promise of capitalist progress were realised and technology did away with fear, confusion, uncertainty and death herself. None of these things would matter, because the human heart would remain not just unchanged, but sicker, sadder and more fearfully deranged.

Consider. If we were able to do away with all the nefarious elites who have a hand in controlling our affairs, if we had a free internet, if the CIA were disbanded, if woke ‘cultural Marxists’ were put back into the silly box they used to play in, if it turned out that we’re all aliens descended from Atlantans living on a flat planet, if we could elect a good government, if we found a miraculous technological solution to the filth we have submerged our beautiful world under, if we could rationally solve all our problems and house ourselves in a gleaming white cube… well then, and so what? Would human beings then become happy, moral, egalitarian comrades? Would technology cease to demand a life of bodiless, hyper-rational alienation? Would the professional class find itself without the means to subjugate us? Would we wake up wild, vivid, free of civilised domestication and all its sense-dimming, conviviality corrupting pressures? Would anything really, meaningfully change?

No. If our world were rationally organised into one of socialist or capitalist perfection, nothing would change. Rationality cannot discover morality nor can it reveal reality, nor, despite the vain hopes of New Stoicism, does it even have any real power over emotional suffering. This is why if the world could be organised to eradicate such suffering it would be a nightmare of the insane.10 To free ourselves of our ills we must use the rational mind, seek reliable facts and form reliable theories, but unless we can move beyond this mind, nothing will or can ever radically change, because the radical, the root, cannot even be perceived by the mind, which chases the causes of its problems, or the problems of the world, like a dog chases its shadow.11

Conspiracy theories, like all theories, help us to deal with the manifest context, and to expose those who have power over it. Without conspiracy theories we would be unaware of the monstrous history of the Spanish empire in the Americas, or of the British empire in India and Africa, or of the century of dropping bombs on faraway places that American arms manufacturers caused wars and, more recently, have overseen NATO, to justify. We would be unaware of the past thousand years of subjugation and conquest which have turned our world into a cinder heap. We would not have before our eyes the mass-slaughter that ‘coalition forces’ committed in Iraq.12 We would know nothing of the crimes of Vladimir Putin in Chechnya and Volodymyr Zelenskyy in the Donbas and Matt Hancock and Anthony ‘the science’ Fauci in British and American care homes and hospitals. The mind-blowing corruption of Saudi, Emirati and Qatari elites would be concealed from us, as would the inhuman exploitation of Chinese factory workers, as would the extermination of the last remaining virgin forests in Brazil, Canada, Indonesia and central Africa, as would the ethnic cleansing of Palestine by Israel.

Yes, thank God for conspiracy theorists. Thank God for Hersh and Pilger and Orwell and Baran and Sweezy and Solzhenitsyn, and Chomsky and Peterson, and everyone who has risked their lives to reveal the conspiracies of the powerful. But. Conspiracy theories cannot reveal the truth of the context, nor can they show mind a way out from the rationalist prison which manifests around it in ever more horrendous, dystopian forms. All conspiracy theories, from flat earth yarbles to useful Marxist analysis of capitalist contradictions, end up exonerating the system, transforming horror into occasions of pathological agency rather than as a feature of the system. Only a fool is against theory, conspiracy or otherwise, but without the ability to see beyond theory, we are no more able to discover what matters to us than a computer can; and as we are all beginning to see, with horrendous clarity, although the computer may far surpass our ability to discover facts and theorise about them, it is insane and can only build an insane world.

‘Kant’s most characteristic doctrines about the mind are now built into the very foundations of cognitive science…’ The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Like parallel lines that meet.

This includes empirical facts; the things grasped by the mind are different to ideas about those things, but in both cases they are isolated and isolable experiences of the mind.

Initially; around the end of 2022 when it became safe to criticise biomedical conversion he came out as a bit of a refusenik. Chomsky still maintains that it would have been okay to let the unvaccinated starve.

Chomsky calls his conspiracy theories ‘systemic analysis’ for much the same reason he calls his democratic socialism ‘anarchism’. See my critique of Chomsky here.

Hannah Arandt, The Origins of Totalitarianism.

Unlike Hitler, whose lies were as ridiculous as they were prodigal.

Among peasants, pre-moderns, barbarians and the like we find much more courage than we do in modern masses.

See I am Security and Hell, No.

It is idle to search for what might have been a cause within a monolithic society. Only that society itself remains the cause. Causality has withdrawn to totality, so to speak. Amidst its system it is no longer distinguishable. The more its concept heeds the scientific mandate to attenuate into abstractness, the less will the simultaneously ultra-condensed web of a universally socialized society permit one condition to be traced back with evidentiality to another single condition. Every state of things is horizontally and vertically tied to all others, touches upon all others, is touched by all others.

Theodore Adorno, Negative Dialectics

Nor would Julian Assange, one of the greatest conspiracy theorists of our time, have spent over a decade rotting away in confinement.