This account is really just for people who read both my work and John Michael Greer’s. This can’t be that many and so, with apologies, I’d like to direct everyone else to next week’s post, and I’ll see you there.

John Michael Greer is a lucid expositor of strange and difficult ideas, a perceptive social critic and a decent fellow. But although his political position1 has the virtue of independence, and although he perceives civilisation from a height that few of his peers can reach, what his exalted eye gains in analytical acuity it loses in empathic intimacy. This is evident in the surface matters he has become popular for; systems analysis, politics and the history of ideas. He doesn’t really stick his neck out on questions of class, gender and race, he is resistant to the possibility of a rapid collapse2, he respects Donald Trump, and, like so many alternative thinkers, he directed little critical attention upon the illusions of Covid when it was happening; only offering a few meek objections when it became safe to do so, long after the vaccines had been rolled out.

But, despite troubling implications, these are trivial problems. It is in his religion, art and philosophy, such as they are, that Greer’s deep-seated shortcomings become most evident. I tried to explore these with the man himself, but he was reluctant to engage unfortunately. He praised my work, which was nice of him, but said he ‘disagreed with my fundamental assumptions’. He wouldn’t go into detail on which assumptions though, or why, perhaps because he’s a busy chap these days and is, as he says, ‘enjoying fifteen minutes of fame’, or perhaps he is less interested in the roots of his thought than I am. In any case, because I disagree with Greer’s fundamental assumptions and am willing to go into detail—from first principles—here is my critique of them.

We must start with the fact that John Michael Greer is a neo-druid. Many of his readers aren’t interested in this, and he keeps the two sides of his work separate, but there is a connection between his metaphyiscs and his politics, which is why the former is buried under layers of arcane lore, why the latter is has the problems it does—shallow, smug-toned, reactionary and extremely light on solutions—and why I propose to take his neo-druidism as seriously as he does.

Neo-druidism is a proto-romantic, occult society of polytheistic nature worship, formed in the eighteenth century by wealthy English gentlemen who reacted to the gross materialism of their newly industrialised society by worshipping natural forces. These men reinvented the original pagan druidism of the original Bronze Age druids—about whom, as Greer notes, almost nothing is known—by cobbling together various myths (primarily Welsh myths as codified in the medieval period, but also various other ‘borrowings’) upon which they founded a complex interpretative system, an even more complex esoteric ‘philosophy,’ and a lexicon of magical rites and rituals that claim to address every problem, both real and not quite so real, that a human being could ever face.

Greer writes at length on all of this. He presents the occult history that neo-druidism is embedded in, lays out the baffling anatomy of its magical multiverse and explains various tricks for tuning oneself into its higher frequencies. Here, as an example of the latter, is a neo-druidic ritual, ‘Opening the Grove,’ a technique of ‘ritual performance’ that, according to Greer, ‘opens a circle of sacred space and brings that circle and the person inside it into contact with the powers of the neo-druid cosmos’.

Raise your right palm forward to salute the Spiritual Sun, which is always symbolically at high noon in the southern sky, and say: Let the powers attend as I am about to open a Grove of Druids in this place. The first duty of Druids assembled in the Sacred Grove is to proclaim peace to the four quarters of the world, for without peace our work cannot proceed. Take the sword from its place, still sheathed, and circle around to the east. Face outward and raise the sword in its sheath, holding it horizontally at head level, right hand on hilt, left on sheath.3

Now, I must stress from the outset that I have nothing against magic rites and rituals, and have even performed some myself.4 I am not one of Greer’s bad guys—the rationalists and the religionists—and I have defended superstition at length. The problem here is not the ritual itself, but that it is not coming from the ground up. It is not an organic expression of a living culture, but something that an intellectual, an educated member of the middle class, has designed. Cosplay. Which is why it feels, to those outside the grove, so silly; silly in a manner that, say, a Ju/'hoansi healing dance, or a Japanese funeral, does not, because modern druids, like the eighteenth-century ‘Ancient Orders’ they draw inspiration from (such as the masons) are, like Greer, urban, middle-class5 intellectuals.

But, you might be thinking, this is all a tad harsh. Does it really matter? In an important sense no, of course it doesn’t. Who cares if someone wants to put a druid’s cowl on, celebrate the triumph of spring or perform the rites of Isis and Pan? They’re not doing any harm are they? And in the case of John Michael Greer, who offers a lot of practical ancillary advice on how to ‘be in tune with nature’—quite possibly, they’re doing some good. But, I submit, such a top-down, outside-in approach to spiritual truth, self-consciously designed by members of the intellectual class, is symptomatic of what is in reality, contrary to its wondrous appearances, an unserious, irresponsible and drearily literal philosophy of existence.

I’ll explain. But to grasp why Greer’s world view is problematic, we need to get down into the metaphysics that his occult multiverse is founded on, which is a cockeyed version of Schopenhauer’s philosophy.6 Greer, like Schopenhauer, divides our experience into representation—what the self presents of reality—and the thing-in-itself—what reality really is, ‘prior’ to what we perceive or conceive. So far so good (I do the same) but, following this, Greer takes the thing-in-itself, again like Schopenhauer (and like many German idealists), to mean will. As we shall see, he uses other words for will, but we’ll stick with this term for now, because Greer, again like Schopenhauer, argues that because the will seems to come to us directly7 it must therefore be the thing in itself.

This is a serious problem for both Greer and Schopenhauer. To understand why means going one step further down into metaphysics, or into the nature of the thing-in-itself, which is—indeed which must be—essentially non-dualist, and therefore not subject to the principle of sufficient reason (PSR), which holds that everything must have a cause, ground or explanation.8 The thing-in-itself—what things really are—transcends all categories that follow from PSR, such as cause and effect, subject and object, and time and space, and so it makes no sense to talk about it as a ‘thing’ in the normal sense. Although the thing-in-itself can be said to be ‘behind’ the manifest universe and to have ‘caused’ it, we must put such words in scare quotes to indicate that this cannot be the literal (mind-knowable) truth. We can only express the ‘relation’ (scare quotes again) between the thing-in-itself and the represented world of the self non-literally; mythically, or artistically, or by saying nothing at all.

Schopenhauer understood all this better than anyone, but because he conflated the thing-in-itself with will, with a thing that is still subject to PSR, that can be thought about and understood, that is part of the manifest self, and that is therefore selfish, he was—or half of him was—led to an appallingly bleak view of the universe, that it only exists to perpetuate the cold, blind, pitiless will.9 I say ‘half’ because another side of Schopenhauer rejected this and spoke—beautifully, and at odds with his caricature as a curmudgeonly pessimist—of the thing-in-itself as being without will, as being the unfathomable ground of existence,10 as being something which demands man overcome his self (in this case overcome his will) in order to directly experience the essential mystery of life. As I say, Schopenhauer was confused,11 but it’s a confusion that can be resolved and that Schopenhauer, in his inspiring work, resolves again and again, despite himself.

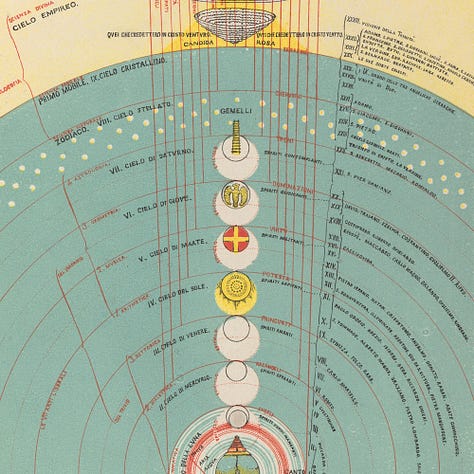

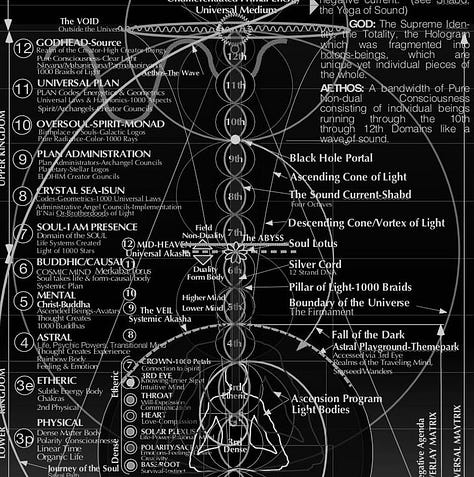

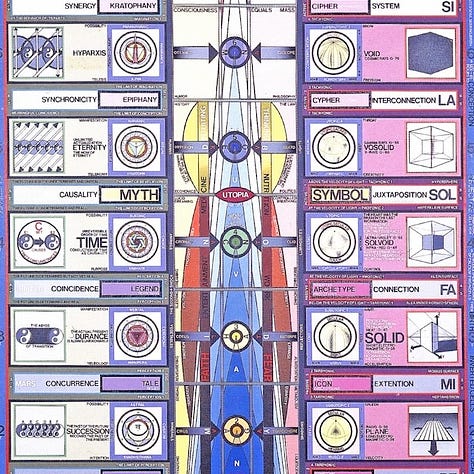

Greer’s confusion is far more serious, because he does not recognise, or appear to seriously consider, the thing-in-itself as being free of PSR, of being causeless, spaceless and timeless. Greer, in other words, rejects primal non-dualism.12 This makes it impossible for him to account for anything of importance—the nature of consciousness, the origin of the universe, the truth of love, the meaning of great art or the heart of spiritual revelation—all of which he understands as literal things within of the byzantine system of hermeticism, or neo-druidic magic. Greer relies on this framework to understand the essentially comprehensible thing of the will, which he variously characterises as a ‘subtle substance’, ‘life force’, or ‘ether’—again, all things, subject to PSR—which are then divided into various other things; higher ‘realms’ (etheric, astral, celestial, etc.), inhabited by a pantheon of entities (gods, angels, demons, spirits; more things) and further divided into a constellation of polarities (microcosm and macrocosm, active and passive, light and dark, etc.). There is some mythic truth in all of this, but the problem is that Greer is forced to take this bafflingly complex taxonomy of the spirit literally.

Why? Ultimately because JMG doesn’t really understand consciousness—the thing-in-itself that I am. His writings on consciousness are contradictory, at times considering it (as Schopenhauer does) to be a function of the will13 (a thing) and at times characterising it as a Gnostic centre of limitless power ‘blazing with the light of a billion suns’ (another thing). Greer can’t see beyond things, and so can’t quite make up his mind what kind of thing consciousness is. He—like so many other thinkers—confuses consciousness, which is always here and has direct access to the thing-in-itself, with mere awareness, which isn’t and doesn’t. He defines magic, for example, as ‘the art and science of causing change in consciousness in accordance with will,’ but on closer inspection he means that magic can change your mind, your emotions, your perceptions and even, paradoxically, your will, which is to say your self and your fluctuating awareness of it; not your consciousness, which is, being ‘beyond’ PSR, changeless; and therefore immune to ‘the art and science of causal’ magic.

Greer of course, cannot really accept that anything is beyond the reach of magic in this way. According to him (and to Schopenhauer) because awareness fluctuates and, having no direct access to reality-in-itself, is untrustworthy, it must be a kind of epiphenomenon of the primal, eternal will (or astral plane, or divine Logos or Gnostic Pleroma or whatever). This allows Greer to focus on various aspects, or [what I call] modes, of selfish representation—the mind, the emotions, the body and the will—and elevate them, literally, to the status of gods, or to the magic polytheistic realm of mystic forces that Greer argues predates and holds more truth than the historical aberration of monotheism.14

I should say that I probably haven’t got the details of Greer’s thought quite right here, because it is very difficult to get at the heart of that philosophy. First of all, he’s written a library of books, far more than I’m prepared to read and secondly, his non-fiction is almost entirely made up of commentary on the work of others,15 and the celestial beings, occult forces, and subtle realms that make up their convoluted occult universe. This obscures what Greer really thinks, or what lies at the heart of his surface thought, while, handily, making it easy for him to handle criticism; for nobody who hasn’t studied contemporary Western magic inside and out can possibly get it quite right, and can be sent beetling back to the Corpus Hermeticum to correct their ignorance.

But the arcane details of Greer’s system are not important here. The point is that he does not and cannot found that system on direct experience of the thing-in-itself—which is to say, on direct experience of consciousness—because that would cut away its foundations. As a literalist, he is uncomfortable discussing these foundations or, as rationalists might say, getting into ‘paradigm disputes’, because that would lead him into a horribly real—I mean horribly intimate—realm that he’s unwilling to visit, and that anyone can visit without the slightest interest in magic, which is why Greer’s work has so little to do with ordinary reality, the place where ordinary people live and die.

Greer writes, to take one of the most conspicuous examples, practically nothing, and certainly nothing very profound, on love between men and women. ‘The secret wisdom of sex’ for Greer comes down to harmonising polarities and aligning your etheric energies, not on actually loving each other, which is to say on overcoming your ordinary stupid loveless self, with all the ordinary emotional distractions that impede men and women from true intimacy. For Greer there is nothing beyond the self, so he finds himself unable to speak meaningfully of reaching the other.

Take this straightforward example. Let’s say you, a man, haven’t been giving your woman the right kind of attention. You’ve been too involved in your work, and are taking her for granted. She gets emotional and makes you suffer, either by flaying you alive with unreasonable spite or by having a week-long darkie. The mood in the house is dreadful. You feel it’s her fault—she’s been so damned cruel or darkly weird about nothing—but when you sit down and try to have a nice sensible talk, like you would with one of the chaps, it just gets worse. The only solution seems to be to flee (into your work, into your mind, into the arms of another) or to violently control the situation; that is, to control her.

Now, what’s the problem here? Is it, as Greer might suggest, that your ‘etheric bodies’ are out of whack? Is there a polarity mismatch going on? Do you need to work with each other’s ‘solar or telluric currents’? Perhaps it’s time to ‘take on the forms of Robin Hood and Maid Marian’?16 Or, here’s another option; is it that you are stupid, loveless and selfish? Is it that you need to face the appalling reality of the situation, overcome your disgraceful attachment to your selfish thoughts and emotions and pour your adoring consciousness into the goddess you live with? I’ll leave that with you, but I suggest that if you take Greer’s approach to this kind of thing, or indeed to any other problem you have with your partner (and they can be a lot more serious than my example), you will never find true love or lasting happiness with him or her. You will reel from one emotional catastrophe to another until you either split up or settle into a ghost world of comfortable, soporific, spiritually dead compromise.

Greer’s attachment to the subtle ‘realms’ of the self explains why his advice concerning self-knowledge amounts to learning symbols17 and why he considers the ego to be, as he says, an ‘essential tool’ for navigating reality, because reality, like the ego, is essentially a dualistic representation. It’s also why, for Greer, the cause of evil in the world is not the pitilessly deceptive self-informed self—something we must overcome to ethically participate in the universe18—but a combination of violating natural principles and ‘thaumaturgic manipulation’,19 which is to say, black magic; an irresponsible philosophy if ever there was one. There is no need to face your cowardliness, your self-indulgent moods, your disgraceful lack of emotional honesty or your mediocrity as a human being (none of which Greer writes intelligently about); no, no, just perform the Lesser Ritual of the Pentagram and you’ll be good. Swap the ‘Sphere of Protection’ for Prozac or half an hour with a therapist and you have the same irresponsibility, less eccentrically packaged.20

As with everything that Greer writes, his diagnosis of our parlous condition, caused by a mixture of dark necromancy and koyaanisqatsi, does express a partial truth, for we do have a nasty habit of careering past natural limits, and we do affect and infect reality, on a deep ‘auric’ level, with our shady fears and desires; but how does this happen? What is it that actually causes us to ignore the principles of nature and to stir dark potions into the clear waters of consciousness? On this—and therefore on any meaningful solution—the archmage is silent. Greer speaks of intellectual recognition, ritualistic practice and ‘participation’, but only in finer and finer modes of the self; emotion, vibe, aura, ether and whatnot. He is not interested in the idea that all these mystic realms are part of the represented world, and so, potentially, part of egoic ignorance, because this would collapse the foundations of his life’s work.

Greer’s refusal to reach beyond the limits of the self forces him into the limitations and contradictions of the very rationalism he rejects. An entirely polar reality, like an entirely rational reality, presupposes its own foundations, making it impossible to ever directly experience what anything is, understand how anything came to be, or ever be sure how any polarity can ever be meaningfully resolved.21 Greer evokes the principle of ‘balance’ or ‘harmony’, but on what is such a principle actually based?22 I’ve not been able to find a meaningful answer to this in Greer’s writings.

Although Greer uses the word ‘participation’23 he doesn’t speak meaningfully of what it is that one participates in, preferring to emphasise what works. We are reminded of Abrahamic religions, which occasionally speak of ‘God’ and ‘paradise’ and so on, but as a kind of appendix to the main business of doing good, and also of scientism, which uses words like ‘beauty’ and ‘truth,’ but which actually comes down to an intellectual obsession with complicated intellectual systems and practical, utilitarian practices based thereon. In both cases, and in the case of occult magic, what works stands in for what is, which is, despite lip service, off the menu.

Greer, like all rational-religious system-builders, is a moral relativist, albeit a spooky one. He satirises the idea that absolute good and evil exist in his Weird of Hali series of novels, which reimagine the creepy ‘Old Ones’ of H.P. Lovecraft’s stories as benevolent (but not too benevolent) helpers in conflict with the nefarious (but not too nefarious) worldly establishment. Greer is critical of Arthur Machen’s understanding of reality as hierarchical and J.R.R. Tolkien’s24 division of Middle Earth into absolute good and evil. He doesn’t criticise these authors for writing two-dimensional characters who are born to service Big Ideas with ham-fisted expositional dialogue though, because, all left-brain25 sci-fi and fantasy authors do this, and their fans don’t notice anything missing. Instead, he simply disposes of half of the human story—that humans are more conscious than bacteria,26 and that there is such a thing as absolute good and evil (which appears, symbolically, in great literature across the world) — in order to place his whole philosophy in the other half, which of course is also true, but only as waves are ‘true’, which is to say, when divorced from particles, false.

Greer, like many sci-fi and fantasy fans (not to mention reductionist scientists) who are maniacally obsessed with high concept fiction and obsessive ‘world-building’ (fan-fiction, that is), calls himself an ‘autist’, which means, he says, that he doesn’t have the ‘brain structure’ to sense other people’s emotions automatically. Putting aside what else it doesn’t allow him to sense (i.e. the thing in itself), this conflates two superficially similar but radically different manifestations of consciousness—emotion and feeling27—in order to sidestep the moral reality that the former betrays, through constant reference to the self, and that the latter intuits, selflessly.

It’s no coincidence that the origin of the word ‘autistic’ is autos, or self, the represented thing-out-of-itself that divides the autist, as it does so many of us in this Age of Autism, from the context. The fact that Greer has problems with feeling through to the inner life of the context explains why much of his writing displays formidable intelligence (elevated ability to focus and recognise patterns, etc.) and amusing directness (blunted social awareness, preference for clarity over agreeableness, etc.). He simply slaps down the observation that, to take a recent example, women from the new middle-class are a pain in the neck for the same reason that the nouveau riche are always demanding (because they are insecure), and to hell with the ire of any ‘Karens’ who might be reading; who, he says, can be reliably dealt with by—get this—‘a quick verbal equivalent of the alpha baboon baring his fangs’. John! Exclamation mark!28

Greer’s lack of empathy then explains why, like many other ‘autists’, he has a yen for intellectual systems,, why his creative-fiction is so barren of character (not just human character either; animals are mentioned, but there is no sense that they have an inner, individual quality) and why an irony-laden sense of humour, founded on word play and in-jokes (a mature version of ‘he fired his +3 arrow at a gazebo!’29) pervades his writing. There is a certain excitable joviality to Greer’s tone, but a notable absence of wild passion or penetrating understanding of the human condition, neither of which, alas, appear in his rather heavy toned (occasionally downright smug) pronouncements. Not because he hasn’t sufficiently engaged with Kant or because there is a flaw in his magical mind-diamond, but because, in the end, he doesn’t really have much to say of real depth. Much of internally-coherent interest, but that’s another matter.

Greer’s essential lack of insight partly comes down to the fact that he is a civilised, middle-class author,30 allergic to conscious reality and to the world of the senses as it presents itself to consciousness; to the kitchen-sink, spit-in-your-eye actuality of life and to the primal ground from which the volk draw their strange rites. In place of love, truth and consciousness, Greer places The Concept, The Will and The Ether. His novels, in which the inner life of unique characters plays no part,31 do not present anything deeper than concepts and forces, no human drama, not really, no insight into the soul, no intimate revelation, and no quotable aperçus based thereon. His essays do not speak of the place he lives in, his books do not open up nature to us as it actually is and his religion does not come from the earth that he loves; it comes from his magical mind. It’s hard not to come to the conclusion that Greer, for all his admirable qualities, hasn’t really lived much of a life at all.32 This isn’t to say that high concepts, intellectual structures, abstract foundations, wyrd vibes and even the subordination of character to plot are not important features of writing, but that by itself the high concept is, like will, aura and even magic, lifeless.

Conclusion

Although this piece is critical, I must stress that I like, respect and will continue to read John Michael Greer. He is a blunt, erudite and perceptive critic of civilisation, one of the best writers on civilisational collapse, and he has rendered fine service to non-causal, animist ‘realms’, which certainly do exist. And although I’ve taken issues with the foundation of his philosophy I am glad that there are people out there like him, ready to dress up as wizards and seriously perform magic. There are living spirits animating this enchanted world, there are realms upon realms, levels upon levels, and there are ritualistic practices that enable man to participate in this strange and wonderful realm we call ‘reality’. Yes, I like Greer and I wished he lived next door to me (although to be fair, that’s partly because my current neighbours are horrible).

My criticism of Greer’s work is that he takes his gods and realms and magic forces, like all religious people do, literally. This is why the whole thing has the faintly absurd air of cosplay and fan fiction, why he says such silly things (which, I’m guessing, half of his readers just ignore33), why his advice is often irresponsible (in that it doesn’t help people actually take responsibility for their problems) and why he remains mired in the same contradictions and confusions that constrain the dreary rationalists and religionists he opposes, that bind all literalists. Forced to treat things as things, they cannot address—only account for—the mysteries of existence, because they cannot directly experience the thing-in-itself. In the end, all they can really do is act—rationalists with concepts and machines; magicians with vibes and charms—but, in the end, both are going round and round and round, trapped in themselves and unable to really help their fellows get out, or get in.

My next critique will be on Paul Kingsnorth, who is a writer, and will never, ever, let you forget it.

And if you’re interested in hatchet jobs and broadsides directed at professional-class radicals, I’ve written pieces on Matt Stone & Trey Parker, Nick Land, David Graeber, Charlie Brooker and Noam Chomsky (none of whom, with the qualified exception of Noam Chomsky, I respect as much as I do John Michael Greer)…

What he called ‘Burkean conservatism’, although he is extremely vague about what this actually entails. As with the rest of Greer’s philosophy when you get to the heart of it, it sort of evaporates in your hands.

The possibility I say, not the likelihood. Consistent with the essential rationalism discussed in this critique, Greer believes that a ‘long descent’ is the only future our civilisation faces. He entirely rules out a precipitous crash, for no other reason that that it has never happened before. But why should this mean it cannot happen to us? We have nuclear weapons for a start, which could precipitate a near-instant and total crash. In addition, our society is vastly more complex and interconnected, and therefore fragile, than any which has preceded it. When I put this to him — acknowledging that progressive cascading failure of the system is far more likely, but that a rapid collapse cannot be ruled out — he shrugged and reiterated that ‘we are following the same path as all previous civilisations’. Yes, John, I know, but…

John Michael Greer, The Druidry Handbook.

Kind of. I live a ritualised life with my wife, I solemnly thanks the animals I eat, I’ve attended and earnestly participated in rituals in Japan (where folk religion still lives), I occasionally meditate and I’ve even been known to do the odd sun salute.

Or the upper end of the working class. I’m thinking of the kind of man who, forty years ago, would have had a train set in his attic, spoken through his nose and been interested in UFOs. The modern accoutrements of nerdishness are things like Led Zeppelin albums, Star Wars figurines, bearbricks and retro-gaming consoles. I’m stereotyping of course, but you get the idea. All quite harmless and endearing, but the usual term of abuse for such people, ‘sad,’ has some truth to it.

John Michael Greer, The World as Will.

Like aura does, or atmosphere, the kind of thing that music, one of Schopenhauer’s chief interests, expresses. These things aren’t really ‘direct’, they are still a manifest part of the self.

If PSR does not apply to a thing, that thing must necessarily be uncaused, unconditioned, and without differentiation (because differentiation implies relationality, which would require reasons), which means it must be unitary. This necessary ‘must be’ is not, however, invulnerable to objection, indeed to an all but unanswerable literalist objection to Kant’s (and Schopenhauer’s) argument, known as the Trendelenburg objection (named after German philosopher and philologist, Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg), which argues that Kant is, as modern neuroscience now accepts, correct in arguing that space and time are self-generated, but his assumption that reality ‘beyond’ space and time is still beyond the categories of existence, is unwarranted.

Kant himself provides critical response to Trendelenburg, through (following Berkeley) his formulation of the ‘no independent access problem’ (that understanding can never step outside representation and verify its own assumptions), as does Schopenhauer who points out the absurdity of assuming that the world out there simply walks into representation and doubles itself, and who argues (an argument apparently unknown to Greer?) that I am a thing-in-itself, and can therefore experience reality for ‘myself’. The problem is that experiencing the ineffable nature of the thing-in-itself for ‘myself’ leaves one unable to literally explain the nature of the experience to those who cannot access the world beyond representation; including, ironically enough, to Kant himself. One most go beyond literality, which the literalist is unable to do.

I explore all this in greater detail in Self and Unself. See The Limits of Literalism for a chewy introduction.

Will, like the subtle spiritual ‘realm’ that Greer is concerned with, is an extension—which is to say not a representation but a manifestation of—the self, and so it is, as Schopenhauer’s pitiless pessimism never ceases to remind us, selfish.

The Brahman of the Upanishads, a book which Schopenhauer loved so much;

In the whole world there is no study so beneficial and so elevating as that of the Upanishads. It has been the solace of my life, it will be the solace of my death.

Largely because of his dreadful experiences with women, starting with his nasty mother, but that’s another story.

It would be more accurate to say ‘doesn’t take non-dualism seriously’. He occasionally uses expressions like ‘beyond time and space’, but doesn’t seriously explore what that would actually mean, and talks about the non-represented world as if it operated according to the laws of this one. In his Magic Monday FAQ for example he deals with this question—How much time goes by between one life and the next?—thus;

It really varies. An infant or young child who dies usually reincarnates right away, but other than that, it depends on the rate at which new bodies are being born, and the particular needs of the individual soul. Some occult writings have it that in ancient times, two incarnations per thousand years was more or less average; more recently it’s been a lot less—thirty years is a common figure in some sources, though it can be a matter of just a few years.

Putting aside the confident presentation of pure speculation, how can one speak of time when that which produces time, the self, is dead?

Julian Jaynes, founds his mad paean to the dominator consciousness, Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, on the same misunderstanding. Jaynes argues that because consciousness comes and goes, doesn’t exist when we are in deep sleep, seems to be located in different parts of the body and so on, that it cannot be primal. In other words, for Jaynes, the evolution of consciousness was an event that occured in civilised history; prior to the Bronze Age schizophrenia men and women were basically insane.

Greer’s arguments for polytheism and against monotheism (in A World Full of Gods–An Inquiry into Polytheism) are persuasive and interesting, but, consistent with the rest of his metaphysics, he dismisses or misunderstands unitary (singular or ‘mono’) consciousness, recognised in polytheistic cultures around the world (The numinous fufuka of the Ufaina people of the Amazon, the Hindu brahma, the Polynesian mana, the New Guinean imunu, the kwoth of the Nuer people, the Mbuti pepo, the Hopi maasauu, the Pawnee tirawa, the Lakota wakantanka, the tao of the Chinese, the aluna of the Columnian Kogi) and either conflates it with the wondrous will—i.e. with an aspect of the self; which explains why Greer’s gods are so bizarrely literal—or with the equally literalist Abrahamic Old Man in the Clouds—which, as heretical forms of Judaism, Islam and Christianity all recognise, can still be taken as a potent metaphor for unitary consciousness. To put this another way, the holy spirit which the neo-druids worship, which they call awen, could be taken to be a monotheistic—albeit impersonal—God to which Silvanus, Mielikki, Eldath, Talos, Auril and all the other gods are subject. Greer would probably object, but there’s no reason not to see it that way.

Greer: ‘my books on magic aren’t especially original, and draw heavily on the insights of Dion Fortune in particular’. He also cites William Walker Atkinson, Eliphas Lévi, Hermes Trismegistus, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers and various other occultists, magicians and pagan philosophers.

Much as I respect Greer, and hate to scoff at such harmless games, the section of his Philosophy and Practice of Polarity Magic where he outlines the ‘Ritual of Robin Hood and Maid Marian’, and particularly the script he offers participants (‘Come with me into the greenwood. Leave behind everything that belongs to the outside world, just as the outlaws of old left behind everything when they fled to the depths of Sherwood forest’) is… well, like I say, I respect the guy. So make up your own mind.

See the chapter ‘Know Yourself’ in Greer’s Learning Ritual Magic Fundamental Theory and Practice for the Solitary Apprentice. He makes a cursory gesture towards ‘wordless and incommunicable’ self-knowledge, suggests you write down your strengths and weaknesses, justifies the esoteric theory of correspondences and describes the symbolism of Chesed. The chapter on ‘Spiritual Development’ in his Circles of Power is similar.

As Schopenhauer perceptively explained, but which Greer, who cannot see ethics as a question of overcoming oneself, misunderstands.

Or, to put it another way, ‘positive evil is the product of forces from outside the solar system setting discordant patterns at work within it [and, at the same time, it] is the product of unforced choices on the part of individual beings.’ From Greer’s The Cosmic Doctrine: The Evolution of a Great Entity.

In this connection I ask myself what wisdom a druid would offer if a woman were to tell him her husband had been sleeping with her sister, or if she asked for help dealing with an abusive father, or if she had just discovered she had less than a month to live, or if her child had just been killed. I can find nothing in Greer’s writings that address the horror of life, the extremes, and I can only hope he would offer something more profound or intimate than ‘the ways of the sacred grove’. It seems unlikely to me though.

A rather depressing consequence of this is, as anyone who investigates Greer’s system will very soon discover, that nearly the whole thing rests on belief. Greer, presumably, would assert that by following the basic rituals of the Golden Dawn magical tradition one can experience for oneself that, say, parallel-reality larvae are eating your soul or that our bodies are drawn from the etheric plane and the astral plane or that Thor literally exists. I have my doubts, but in any case, until one has reached the higher levels of druidry you’ll just have to take his word for it, or the word of the authors he ‘draws heavily on’. Sound familiar? Yes, it’s another religion. You don’t know, unless you’ve studied the ‘lore’ for decades—or perhaps you can’t ever know? In either case, best to just accept the word of the ordained, in this case, an old magician who’s been at this game, oh my oh my, for a long, long time now.

This isn’t to say that one cannot experience bizarre realities and then report them back to others. My point is that Greer’s system is massively overladen with hyper-abstract ideas (symbols, correspondences, polarities, etc, etc.) that the reader simply has to take on faith. In matters of importance, Greer almost never refers the reader to his or her own actual experience, or highlights that experience with original observations on the human condition. He doesn’t really explain; he explains away, by reference to his baffling system. This is all very gratifying to readers who are also not really interested in their own lives, but to anyone else it’s like reading about the logic of Star Trek physics or the turgid backstory of The Lord of the Rings.

Or, to put it another way, how was druidic prime-mover Einigen the Giant, ‘the first of all beings’ himself created?

And rejects the idea that magic is not a means of control—although not very convincingly to my mind. If you think you are the subject of hostile magic and you construct a home-made amulet to ward it off what else are you doing but controlling the situation to your advantage? Exerting your control over whoever or whatever you think the hostile magic is coming from?

I am using this term in a loose, conversational, metaphorical sense.

And that humans naturally organise themselves into hierarchies (albeit shallow hierarchies without the power to coerce). Greer, true to his middle-class values, does not, as far as I know, uses the word ‘hierarchy’ in a positive sense.

Not to mention sympathy and empathy.

Greer says he dislikes comedy intensely because, with the exception of farce, it is always founded on violence. Not true.

He describes himself as coming from ‘the ragged bottom edge of the middle class with parents who had been raised working class’, although I am referring more to his sensibility than to his origins. Meaningful enquiries into class (not to mention race and gender) do not appear in his work.

Readers will note the absence of any serious discussion, or in most cases, mention, of any great literature, at all. Chaucer, Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Boccaccio, Fielding, Goethe, Dickens, Balzac, Tolstoy, Conrad, Proust, Kafka? Nope. He’s a nature writer who doesn’t mention Clare, Wordsworth, Lawrence or Hardy and an American writer who doesn’t mention Emerson, Whitman, Thoreau or Melville. Perhaps he ‘doesn’t have the brain structure’ that would allow him to sense great artist’s mighty souls ‘automatically’? He does have the brain structure to appreciate the ideas of Machen though, and Hodgson, and Le Guin, and Blackwood, and Tolkien, and Lovecraft, and, Lovecraft, and Lovecraft.

He says that the ‘whole notion that literature and the arts exist so that writers and artists can ‘express themselves’ belongs in the trash heap, since writers and artists are no more interesting than anybody else’. Once again Greer confuses self—the self of the writer, which nobody but the writer is really interested in—and unself—the writer’s unselfish quality, which certainly does make him more interesting than anyone else, if, unlike everyone else, he can find a way down to it. Those who, like Greer, cannot, are eager to promote the fake humility of the scientist. ‘It’s not about me, it’s about the data’.

Such as his guide to ‘effective magical combat in the political sphere’. Bear in mind that this kind of thing is not peripheral for Greer, but central.