This two-part essay, previously published as Panjective Art (in Ad Radicem) is an introductory overview of the history of art, laying the ground for a few more detailed enquiries to come.

Prehistoric art

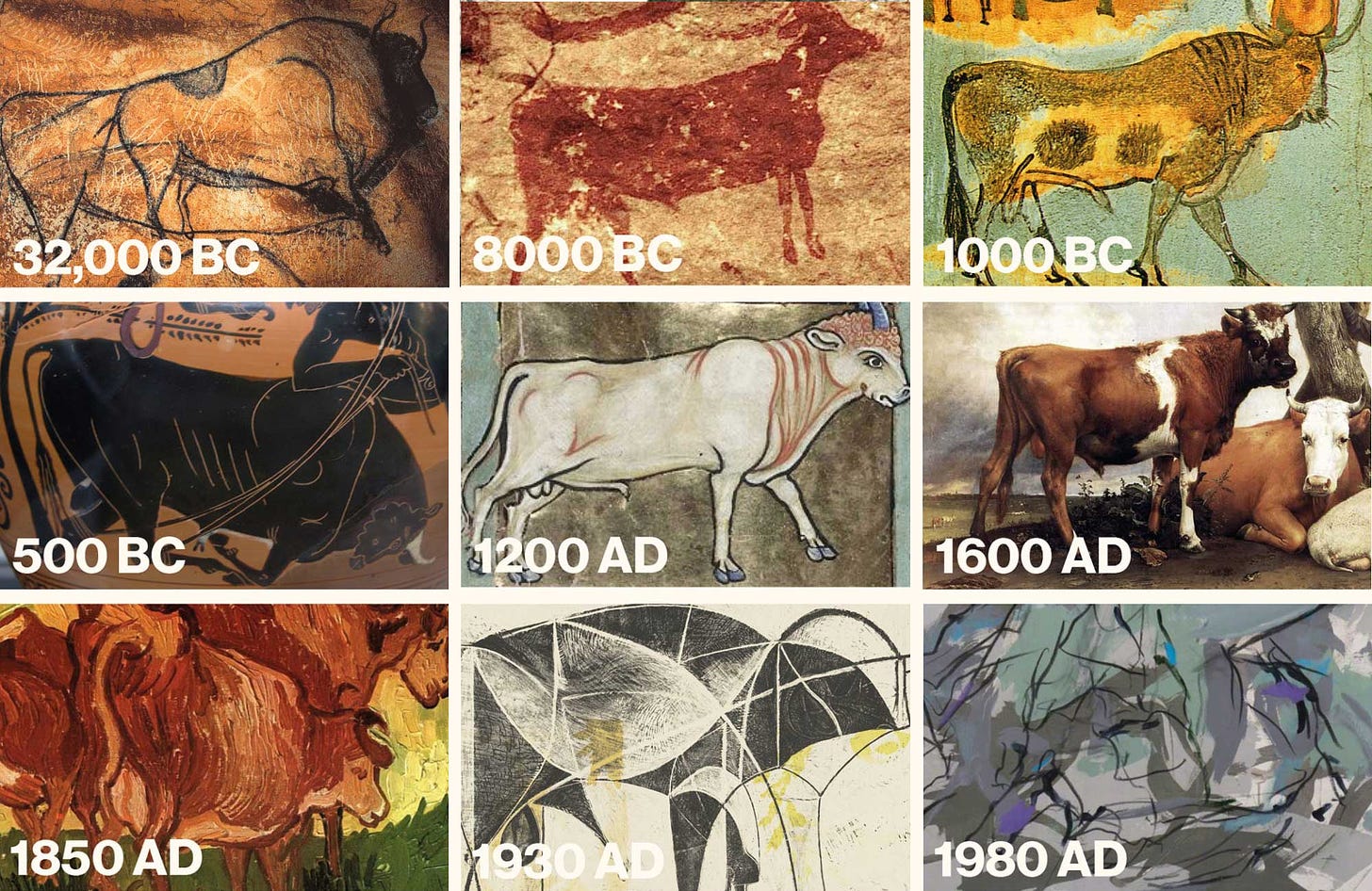

The earliest ‘artists’ did not endeavour to represent the clear objective outer form of things, in which lines and colours are distinctly and rationally reproduced, nor did they attempt to express a personal, subjective (or religiously determined) state of existential fear or desire. The earliest artistic images were expressions of panjectivity. Objects were not perceived as hard, isolated forms, but as fluid expressions of a felt reality in which the context ‘out there’ blended with the consciousness of the observer ‘in here’, and from which both the objective time and space and the subjective thoughts and feelings of the self emerged.

The bull, for example, was not the threatening lump of meat we occasionally pass on a walking holiday, nor was it a unit of economic productivity, nor was it even the mythic symbol of male aggression and power around which the cults of early civilisation formed. In prehistory the bull was the face of life and death itself, the blood of fertility bowing its horns before—and as—the moon, the roaring earth dignified and horned and, far beyond any kind of poetry, ultimately an apocalyptic mystery in the flesh. Like everything else it was itself, but it was other; man, beast and the unfathomable living thing-in-itself of ‘bullness’ that both the art and the bull expressed (just as, for example, the word ‘spirit’ meant both spirit and wind).

This enigmatic otherness was not apprehended imaginatively or speculatively, as a whimsical illusion, or sentimentally, as a totemic symbol, but erupting in the heart, with catastrophic gaiety, represented, as it is, with free vibrating strokes, a vivid inner life sweeping across fields of darkness. The power and character of the bull, like that of any animal, existed within, in this inner abyss, of the still, dark mind-at-large which primal people sought to embrace, and without, in the still, dark caves that primal people sought to be embraced by. The panjective image was an expression from and, as it were, a window into the quality of the thing-in-itself, which the viewer saw through, into his own qualitative experience.

These earliest images (such as can be seen in, for example the Chauvet cave paintings of 25,000 BC) are multi-dimensional, integrated into a complete sensory experience. Each animal is different, unique; there is no uniform design, no emblematic totemism, no appeal to the abstract mind. Painted in caves deep underground, viewable only by candlelight, they shift and glow; they live, and through the conscious experience of this life, they communicate psychologically transcendent realities to the reverent beholder; the sense that the living quality of the animal is a function of consciousness, that I am that. The greatest religious art which was to follow, and which still speaks to us from the far East and the depths of the Dark Ages, did much the same.

The sense that reality lives—that, miraculously, it has the quality of a living creature—suffuses all primal and panjective art. The universe was consciously felt and conceived as an organism; fundamentally benevolent, productive, mysterious and impenetrable to the rational mind; which is to say, female. Not that creation was ruled over by ‘a female god’, but that reality itself was understood to be somehow feminine.

There appear to have been two conceptions of this femininity. One was the enormous, round, life-woman, with ‘shelf effect’ buttocks and pendulous, milk-heavy breasts, and the other, a straight, skinny woman. Impossible to say for sure if either was understood differently. Some say that the big girls represented the universe in its creative sense and the thinner, more stylised figurines were tomb goddesses. But whatever their individual meaning and function (and a few are a bit creepy, Lord only knows what some of our ancestors were up to) the paintings and sculptures of prehistoric art, as a whole, seem to express a mysterious reality in which men and women were profoundly at home and of which they were profoundly in awe.

And yet. The archaeological record is surprisingly bare of truly ancient art. John Zerzan and Barry Long both plausibly suggest that art was as unnecessary for early people as it may one day be for us. Blended as they were with the panjective actuality of reality, they had no need for any kind of objectifying, sense-separating, representational activity; the cave paintings and mystic figurines we admire for their virtuosity may actually represent the first steps in a degradation of conscious life, the beginning of superstition, whereby images and myths, controlled by a central shaman figure, stood in for a lived experience that was beginning to slip away.

Whatever the truth of the earliest art, we can be sure that living experience did slip away and that classical art represented our tragic estrangement.

Classical Art

Around ten or twelve thousand years ago a massive shift in representation occurred. The animals of panjective sympathy became the beasts of subjective-objective symbolism. We begin to find, in the stone pillar complexes, rock buildings and burial sites, a new animal; not one of attachment but of disconnection, of abstraction. There is now the sense that we have our place and they, theirs; an inner and outer world which divides the human from the animal. The pictures become fixed and unmoving carvings, exposed to daylight. They are also clumsy, garish. Dangerous and predatory creatures—leopards, cheetahs, foxes, scorpions, lions and wolves—now become the norm. The thinking seems to be that small fields of domesticated animals and grains were protected from wild animals by more formidable animal spirits, and that the dead would help defend living people against the threatening wild. The animal in art—like woman in art—is now no longer an intimate subject of experience, but an object to be tamed, mastered or defeated; either food (what I want) or threat (what I don’t want). This is the beginning of porn.

Early ‘civilisation’ began with proto-cities like Çatalhöyük, in present-day Turkey, which were overcome by or grew into the early states of Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Semitic-Aryan societies of the fertile crescent (the forefathers of Greece and Rome). As ‘civilised’ history progressed, so the sweet, stirring strangeness of nature, innocence, mystery, femininity and life-loving art declined, along with those cultures that still valued such unselfish realities, which were crushed or assimilated by ‘the iron cage’. Artists were now cut off from the darkness of life and portrayed death, not as it had been previously—a splendid continuance of the subtle mystery of life—but as suffering, loss and torturous obscurity. The purpose of art became either to depict an objective reality or to subjectively impress, frighten and conspicuously display power and wealth. Violent clashes between crude, aggressive and increasingly abstract animals became common, along with terrible scenes of punishment and warfare, enemies being beheaded, slain and skinned alive.

‘Civilised’ art, therefore, was initially subordinated to the selfish subjective emotions of fear and desire. As civilisation evolved, the emphasis changed to equally selfish objective ideas of accuracy—which to say, essentially there was no change at all, for both occur in the represented self. By the time we reach Greece and Rome the purpose of art has become to habituate us to an entirely symbolic reality, to deify the state and glorify the body—not as bodies actually are, in their ineffable particularity and sensuality, but subordinated to a rigid ideal of what they should be. The figures and scenes are now incredibly accurate; but, like classical monuments, scooped out shells; no more truthful, fundamentally, than those of the superstitious barbarians they detested.

Does this mean there were no great works of art in early civilisation? Was all artistic output between 10,000 BC and the birth of Christ devoid of artistic truth? Obviously not—the point is that the illusory subjective-objective matrix which has dominated all cultural output since the dawn of recorded time, is inimical to unselfish panjective expression—to artistic truth. When such art appears it inevitably comes clothed in the style and form of the time—it has to—but it is essentially independent of it; which is why it is so often violently rejected by the time in which it appears.

The objective realism of classical culture ceded to a form of radical subjectivity in which symbolic forms, standing in for non-sensory experience—the Western, transcendental, Abrahamic God, or the Eastern, immanent, divine nature of the godhead—again predominated. Although superstition, state power and ideological religious subservience certainly continued—and with them pornographic art—such totalising cultural forces were largely a project of a Western ‘civilisation’ which a) broke up with the fall of Rome and b) never had quite the same grip on the Eastern psyche. Consequently, in the early medieval era, in the West and in the East, we see greater freedom of expression in art, more vivid characterisation and finer panjective quality—often grounded in sensate experience of the balance and personality of the natural world.

Panjective pre-modern medieval art of the East and West may (like the pre-civilised masks of the Inuits or the pre-Roman tomb art of Etruria) seem naive and ‘childish’, but (unlike the crude daubings of recent years) it is often overflowing with character, sweetness and an intimate sense of the living quality of ‘inanimate’ matter. We are invited to see through the medieval icon into the mystery of God or the panjective passion of the Christ. There is a felt sensitivity to the natural world, to the character of animals which, as objectivity returns to art and the humanist renaissance strikes, begins once more to fade, and charming, psychologically truthful, art, which was common in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (reaching their final majestic peak, two centuries later, with the work of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel), once again vanishes.

The watershed moment in Western art history came at the end of the first millennium after Christ, when panjectivity in Western Europe gave way to objectivity; to objectively ‘accurate’ representations of the dead Christ on the cross, or to scenes from the Bible which were supposed to merely re-mind believers of their religious and ethical commitments. In the Eastern Orthodox Church panjectivity lived on in religious icons, the truth of which was not to be learnt, or known, or even looked at, but participated with.

The West rediscovered objective imagery, and the objective eye again purported to paint ‘reality’ as it ‘really is’. Given that this ‘reality’ is and can only ever be the representation which the mind presents to man, worship of such art was and continues to be idolatry. Unifying quality necessarily fades away from the merely accurate or merely useful. This change in emphasis manifested as—and may even have helped lay the foundation for—the rediscovery of so-called ‘objective’ science and, with it, the technical discovery of ‘objective’ perspective, the great innovation of the Late Middle Ages which heralded the birth, in art, of the modern age, in which mind-made objectivity claimed to be reality itself.1

Perspectival pictures present themselves as—and are widely taken to be—more ‘realistic’, or more ‘like reality’ than non-perspectival representations; but this is false. First of all they only represent the mind-made ‘civilised’ world—there is no perspective in nature, because there are no straight lines. Secondly, these straight lines force the viewer, and the painter, to subordinate the whole of the image to a concentrated [vanishing] point. The lines of the walls, roads and tiles are not to be viewed in themselves, but as symbolic markers for the perspectival idea of the isolated viewer.2 Points on a plane are not, in perspectival images, expressions of essence but subservient signifiers of uniform, mind-made, space and time, used to emphasise the illusion of solidity and homogeneity, and to de-emphasise both the role consciousness has in creating and perceiving experience and the self has in forming space and time. The distortion of objects in perspective does not actually exist. We are, in effect, tricked into thinking we are viewing an accurate representation of reality, whereas we are actually viewing a highly abstract matrix of interlocking symbols representing an illusion.

This isn’t to say that artistic truth cannot be expressed in perspectival images (or that perspective is literally invented—clearly it is in some sense real), any more than that truth cannot be expressed in abstract language or maths. Rather, perspective is not an accurate representation but a realistic form of objective interpretation, and the cultural drive to worship this form, which began in the 1500s, ends up suffocating ‘unrealistic’ natural, sensate, qualities and alternative, personal, expressions of that which is represented; not just individually, but collectively. A felt inner experience of reality, of the body, of society and of the world is supplanted by a logically consistent structure of externally (not to mention professionally) generated and managed symbolic forms. Man ceases to sense himself, and then understand that sensation through the mythos of his own society and psyche, and instead learns to see himself, as an object among objects, comprised of atomic parts which the objective world forces upon him.

The Renaissance also saw the erosion of the artisan and the craftsman. The idea of the ‘professional artist’ was foreign to human experience before modern times. There were just men and women who made buildings, pots, paintings, and tapestries. Nobody thought to sign paintings, no famous architects left their names to posterity, and we have no idea who was responsible for most of the revered masterpieces of pre-modern times. This wasn’t just because people were less egoic—although this is true—but because they were less professional, a category of artist, whose standards of judgement were radically different to those of the traditional craftsmen, that began to emerge in the 17th and 18th centuries.

We now see a set of professional skills, a standard, begin to shape artistic output. Anyone who has not learnt those skills, in the correct manner—and increasingly, in the correct institution—is, by that very fact, unable to create art. The ‘primitive’ artist (a word which was used for non-civilised and lower-class painters) is now beneath us in the arts just as surely, and for much the same reason, as she is beneath us in the sciences. Outsiders may eventually beat their way through the heavenly gate, but they are never given the keys.

Just as professionalisation and institutionalisation removed the creation of art from the hands of ordinary people, so it removed the use and appreciation of art from the context in which it was once embedded. The beginning of the nineteenth century saw the first museum, a place we were supposed to go to enjoy cultural artefacts. No longer was art made for walls—much less for kitchen tables—it was to be seen—actually stared at—in the proper place, the gallery, presided over by professional experts. This was the start of a process that would end with artists who wished to succeed having to produce work not for places of living and the people who lived in them, but for places of consumption and the people who owned and managed them.

Any art which disrupted the increasingly dominant prerogatives of capital or which did not fit with the deformed aesthetic of owners and managers, simply didn’t count. The end result of this process was that artistic creation was completely torn from its context, from the place and time it was produced, so that it could be infinitely duplicated and reduplicated in order to associate the image of art with the transient, largely market-dependent, need of whoever was manipulating its symbolic reproduction. The transcendent, panjective purpose of art was hollowed out into a series of mere tokens which, like social media notifications, are only ever for me, for my purposes.3

The new aesthetic of capitalist art necessarily privileged form over function. The professional and possessing classes had, as they still have, a distaste for function—for material reality—built in from birth. They don’t, on the whole, do anything really useful, they don’t make or have to deal with real things, they don’t have to rely on real people for support or for the experience of their real senses for knowledge. They have a pre-programmed distrust of the future, which they view through the lens of financial security, and an inbuilt distaste for the imminence of matter and the transcendence of consciousness, all of which is reflected in their bizarre attitude towards art, which focuses almost exclusively on what the image is ‘about’, how it was made, who the artist is, what it reminds them of, how it makes them feel, where it is ‘situated’ (in history or philosophy) and of course, how much it is worth. To ask what the painting is actually of, what we are actually looking at, is taboo, a laughably naive question which has no place in serious art curation or criticism.

Perhaps you have noticed the extraordinary way the privileged classes greet art; by paying no attention, whatsoever, to what it represents, or to what is actually there in front of them? The foolish commoner might say ‘but it’s just a stuffed sheep!’ or ‘that’s just disgusting!’ while the knowledgeable art critic snorts into her Chablis. The focus of the bourgeois critic on form, style and concept mirrors the drive of the bourgeois artist to speak through form, style and concept; because pre-formal sensory experience is distasteful to them both. The same is true of film (ooh, wonderful cinematography!), story (ooh, powerful language!), and each other (ooh, nice house!). The function, much less the reality, of art and life is simply off the menu for the formal classes.

The rise of the professional artist therefore went hand in hand with the rise of the professional art critic and curator. It also travelled in tandem with another related process, the decline of objectivity in art. The beginning of the nineteenth century signalled, firstly, another cultural turn away from classical, rational mentation back towards instinctive, romantic emotion. Bach gave way to Beethoven, Gainsborough ceded to Turner and Kant yielded to Schopenhauer. The pendulum was once again swinging back to subjectivity.4

In addition, objectivity in art was being usurped by the camera, a machine which seemed to be able to capture in an instant what Titian and Raphael took weeks and months to achieve. This ‘seemed’, however, was the flaw in the realistic jewel. Artists realised that although photographs could capture the rational appearance of the object perfectly, they left no room for the fluid blended mystery of its essence, the flavour of it, the life of it5 and the human response to it. Photographs may be amusing, accurate or exciting, they might stimulate memory and, particularly if the shot is taken during an idiosyncratic or unguarded moment, be a fascinating and useful revelation of the open-day; but they rob the witnessing subject of its empathic response. Strangeness, delicacy, character, vibe, light and the living blood of the witness cannot survive the transition to technically accurate film, and although it may sometimes be possible to identify the photographer from her photograph, through her choice of subject, film and technology, the work reveals next to nothing of its creator. Photographs, by their nature, deny, or intensely limit subjective experience, just as hyper ‘realistic’ objective art, denied the subjective mystery-loving civilisations they encountered, such as Minoan Crete and Etruria.

The combined influence of professionalism, romanticism, photography and alienating technological progress (cities, railways and factories) led to a new, extreme form of subjectivity in art. Artists began to once again consider their personal experience or interpretation to be as important as the objective fact of what was happening, but unlike in the medieval and prehistoric past, this objectivity was now unreachable, profane, boring. The ‘real world’ was now the preserve of practical men of business and science, while the inner world, although rich with ‘artistic truth’, was effectively impotent. The civilised split between subjectivity and objectivity was becoming a gulf.

Part Two Next Week

Our understanding of light also changed. Medieval images show things glowing with their own light, renaissance forms are lit by external sources. See Ivan Illich, The Scopic Past and the Ethics of the Gaze.

Erwin Panofksy, Perspective as Symbolic Form. See Svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century.

See Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

And, as I’ll outline in a future essay, boredom.

In the course of his famous conversations with the sculptor, Paul Gsell remarked, apropos Rodin’s The Age of Bronze and St. John the Baptist, ‘I am still left wondering how those great lumps of bronze or stone actually seem to move, how obviously immobile figures appear to act and even to be making pretty strenuous efforts.

Rodin retorts, ‘Have you ever looked closely at instantaneous photographs of men in motion? ... Well then, what have you noticed?’

‘That they never seem to be making headway. Generally, they seem to be standing still on one leg, or hopping.’

‘Exactly! Take my St John, for example. I’ve shown him with both feet on the ground, whereas an instantaneous photograph taken of a model performing the same movement would most likely show the back foot already raised and moving forward. Or else the reverse — the front foot would not yet be on the ground if the back leg in the photograph were in the same position as in my statue. That is precisely why the model in the photograph would have the bizarre look of a man suddenly struck with paralysis. Which confirms what I was just saying about movement in art. People in photographs suddenly seem frozen in mid-air, despite being caught in full swing: this is because every part of their body is reproduced at exactly the same twentieth or fortieth of a second, so there is no gradual unfolding of a gesture, as there is in art.’

Gsell objects, ‘So, when art interprets movement and finds itself completely at loggerheads with photography, which is an unimpeachable mechanical witness, art obviously distorts the truth.’

‘No’, Rodin replies, ‘It is art that tells the truth and photography that lies. For in reality time does not stand still, and if the artist manages to give the impression that a gesture is being executed over several seconds, their work is certainly much less conventional than the scientific image in which time is abruptly suspended. ...’

Paul Virilio, The Vision Machine.