Sleep does not refresh. The room beyond the duvet is enemy territory, a hostile universe, cold and full of separate things. I will never be able to leave the bed—not ever—but in the middle of an everlasting no, I am surprised to find myself up.

Freezing in the kitchen, numb light picks out last night’s squalid crumbs. Jacqui watches the toaster. She is two or three times bigger than usual, and more solid; her resistance to the world—and, as I am the most threatening part of it, to me—fills the room. I can’t help myself though:

‘I think Jonas is going to be pretty cheesed off with you.’

‘Oh I know! Isn’t it marvellous?’ she says, brightening up instantly and swanning back upstairs.

She brought the most unlikely man back last night. He looked like everyone’s angry uncle, a thin-nosed bald lawyer type called George, who combined strait-laced financial-district aggression and suspicion, with an inability to put his body where it should go. He stood in the doorway of the kitchen, and we all thought ‘I don’t think so,’ and then he was gone to fuck Jacqui in Jonas’ bedroom.

Jacqui no more felt at home in Jonas’ sterile white German design-studio of a bedroom than he did in hers. Her room was forty-five years of gaudy; layered up like a gigantic surrealist cake—cracked bulbless Tiffany lamps, sequinned pillows, a large latex elk head mask, stolen Muslim prayer mats, broken accordions (×2), a cheese-grater in a mouldy fish-bowl, Victorian crates covered in photos, Norwegian postcards, tailor’s busts, dolls with missing eyeballs, snapped mobiles and jam jars everywhere stuffed with unwashed paintbrushes, blunt pencils and clogged dipping pens—this the base layer, the sponge; on top of which lay perhaps ten or twelve wardrobes of clashing clothing—yellow and black dresses, huge white and scarlet plastic bangles, blazing pink mohair jumpers, bumblebee kitten heels—all expensive stuff, all extraordinarily tasteless—before, finally, a sprinkling of letters, bills, crockery, crisp-packets, cd covers, crumbs, loose tobacco and a tin of canned bear paw.

George had taken one look at this cathedral of bibelots and whim-whams and said ‘I’m not fucking you in there,’ and, without missing a beat, she’d said ‘fine,’ and taken him up to Jonas.’

I haven’t eaten now for thirty-six hours and feel like someone has poured a bowl of bitter soup into my cranium. Jacqui’s toast and sausages (fried in vegetarian Jonas’ vegetable-only frying pan) aren’t doing it for me though. Apparently, my body has given up asking for food. It’s got the message now. I’m going through with this, but I’m going to take it easy, get the bus for a change.

Out in the street Igwe is resting on his broom facing two school kids, maybe eight years old, walking with their mother on the other side of the road, and he is calling out to them, ‘Hello! You are good boys! You are gooood boys!’

The mother looks back and smiles thinly, the children pay him no attention, but Igwe keeps calling out, long after they have gone, ‘Bye! Bye! Byeeee!’

Then he sees me and walks over rapidly, his skinny arm outstretched. I don’t want to talk, but Igwe is skilled in roping me in with his big pink gums theatrically mouthing words of great joy and earnest entreaty.

He triggers his elbow, going in for the black man handshake. I’m never really quite sure how to greet Igwe—or how to greet anyone; there’s just no damn protocol! Usually I just wait to see what happens and do likewise, but the black man feels ridiculous, so as usual I go in fingers down with a whitey, and as usual we settle on a halfway palm-touch which is more ridiculous and awkward than either.

‘I don’t know why you are not on your bicycle anymore,’ he says, confused, almost hurt.

‘I’ve got lots to do Igwe, I don’t have time…’

‘No time? You are going to die!’

‘Maybe.’

‘Not maybe. Yeeesssss,’ he hisses.

‘Yes, okay, I am going to die, yes.’

‘Listen to me. You look better on the bike: more alive, awake, you are wiiiider.’ He spreads his arms. ‘But today you are thin and like everyone else.’

‘I am like everyone else.’

‘No! You have conscience, and conscience is God.’

‘Don’t other people have conscience?’

‘Do we live in this darkness if the people have conscience?’

‘No, I suppose not.’

‘Hear me,’ he says, ‘if you give me 420 pounds, God will give it back to you a hundred times.’

‘Yes, I asked God if I should give you the money, and he said I shouldn’t.’

Igwe’s eyes widen like a 3-year-old’s.

‘What?’ he says, ‘You have the money?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you are not going to give?’

‘Yes, strange isn’t it?’

Igwe bursts into loud, unrestrained laughter. I smile. I don’t want to, but I do.

‘Look Igwe, I really must go.’

I slope away, Igwe calling after me down the street, ‘I like you!’

It starts raining, thin, freezing, gusting. There is no room under the bus stop shelter so I have to take the brunt of it, clenched up, resisting it. The 484 is late, so everyone is peering down the road, straining for the bus to appear, trying, through force of want, to force it into existence.

Slowly passing headlights, thin rain, chug of waiting buses, suffocating acrid smell of diesel, cigarette smoke and dog-shit. The Mumbling Man shuffles past muttering to himself; enormous nose, no chin, spindle-thin, soft, smooth milky head, guilty look in his eyes. An overweight couple; the girl’s folds of perfectly delineated fat spatulared into a tight red t-shirt proclaiming the legend ‘pin up,’ the man’s hairy jewelled hand proprietorially splayed over her wide rubber arse. A push-chair, young boy, face puffy, red-eyed and wet with rain and tears, is screaming, his skinny mother behind, wearing earphones and smoking, pays no attention. Another couple of kids are fighting—a boy of five or so is smacking his sister over the head with a plastic sword. His distracted father hears her screams and tears into the boy as the bus roaringly arrives and I press myself in. The bus pulls away. The little boy outside is looking in at me, specifically at me, while his dad shouts at him. He theatrically draws the sword across his throat and then collapses into a puddle.

It is close inside, hot, cramped. Bodies bob and jostle. Greasy matter presses down, open pores, mass, fat, organs, bile, shifting around, getting near me. Not so bad in the morning though, because most people have washed. The woman next to me looks like she has steel bars for neck-tendons, but she smells nice and I comfort myself with that, although I feel a bit sordid smelling a stranger, even if it is for existential solace.

Two black girls are talking loudly, far too loudly. The nearest has scalp-stretchingly tight plaits.

‘’E knows not to call on me. I’m not silly.’

‘Dat boy is ignorant.’

People who talk too loudly never say things worth overhearing.

A life-crushed Chinese woman sits across from them, her toes squashed into her shoes, making four plump, red, little cleavages. Next to her a couple, he distractedly explaining something, she smiling falsely, not listening, not interested. Behind them a middle-aged man looks like he is about to cry, lips pouted and trembling, eyebrows pushed diagonally upwards in blubby despair.

All the facial features seem slightly too big, or too small, or too close together. I think of God on a conveyor belt of nice symmetrical faces, getting bored, and pulling them about, tongue out to rubbery stretching sounds. He intended this batch to be angels, but, in the end, he couldn’t be bothered to do a decent job and I quite understand, because; neither can I.

I get off at Trafalgar Square, and walk north through Covent Garden to Seven Dials. People pass, and I endeavour to see them—I just can’t help myself, even though I know that each look is like diving naked into an empty swimming pool.

It’s one of the obvious facts of life, that everyone is thinking to themselves, but, like so many obvious facts of life, to really experience it is quite shocking, like the surprise you get when talking with someone and they say something which shows they haven’t been listening to a word you’ve been saying, or when someone accuses you of something you can’t possibly be guilty of. You know that life is like this, that people don’t pay attention or that they nurse bizarre ideas about you, but when it happens it’s as if it’s the first time; totally out of the blue.

They can’t think of anything better to do than admin.

And so I walk in a state of out of the blue up to the plexiglass doors of Financial Objects and into the unnaturally hot reception. I have always thought that the worst thing about work is the smell of the carpets. The moment I walk in the whole experience of job suffuses into my core self, not this or that indignity or frustration, but the total bodily horror of it. My heart clenches and the walls slide in somewhat but, as usual, momentum carries me forward, overrules the animal instinct to run, run, and I mumble my hellos on the way to my desk which, for some reason (I mean Lord knows why they gave it to me) is the best on the floor, at least to my perspective, tucked in the corner with no way for anyone to see what I am doing.

I sit down. 8:45—poor timing! A whole fifteen minutes I’ve given away of my life, and an hour and a half until the first tea break. I look out the window across Monmouth Street into the offices over the road—an insurance company, or a fashionable publishing company, or something like that—and down over the last of the commuters, struggling to work, and the first of the tourists, struggling to fun; ghosts, immaterial dreamselves floating along, passing through walls and then doing what ghosts do, staring at strangers having sex, staring at other people’s crimes, staring at famous places, secretly following old lovers around, getting pretend revenge on enemies, thrusting their bodiless heads through the insides of bodiless statues, or bodiless cows, flying their ghost eyes around neat 3d worlds or floating through empty space. That’s what ghosts do. I turn back to the internet and do the same.

9:00 hits and it’s time to pretend to work. I delay the inevitable for a few seconds by going to the stationery cupboard, past Don Broderick, a long-bodied, tall-browed, very much law-abiding American; past Geoff McCray, ‘Mr Nice,’ a tight-fisted, cynical, self loving Scot with no personality to speak of, who hides this from himself and others by being excessively helpful; past Ralph, a sad carp in tinted shades whose only topic of conversation is the house he’s redecorating or, if anyone gets close enough, his reptile-minded ex-wife; past my boss, Tina Ween, a short, plump, frizzy, ever-fretting, ever-fussing woman of indeterminate age (late twenties? early forties?); past her boss, Graham, he of the ball-bearing head and immaculate beard, who does his best to make everyone feel special and indispensable, but he only ever leaves the impression not so much of being special and indispensable, more of being a small, plastic, very much dispensable, pellet.

Of my two bosses Tina is the more dangerous, despite her faffing, tutting treatment of everything and everyone as an unruly menial. Graham is glinting, wrapped and bound, with an unswerving commitment to his professional self, but like all men, at least all men in business, he can’t really see me. He thinks—to my constant astonishment—that I am basically just like him (an anxious, driven, fundamentally untrustworthy spiritual bureaucrat) whereas Tina knows in her flesh that I am out of place here, an alien artefact from another dimension, protruding threateningly into this one.

I am most vulnerable when I am most myself. An unguarded moment of honesty, an expression of true delight or disgust and the internal censor pings on, running over what they will make of it, assessing where it rates on the Universal Scale of Non-cooperative Weirdness.

Already, walking back to my desk with my sad, futile pencil, I very much have the feeling that, you know, Christ, that I have come to this—that we have come to this—aren’t we supposed to be riding wild horses through virgin valleys, chanting in warm wet forests, or writing long, loving poems on row-boats… and not converting RTFs to PDFs all week? Or something nobler, at least, than ‘office, flat, shop, repeat’?

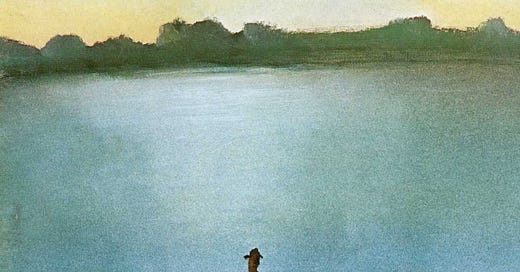

Such is my thinking at 9:08. I turn to my computer and, to calm myself, I look at some paintings by Edvard Munch and some drawings by John Bauer, but it doesn’t help. It just makes my own work—I mean my real work—look all the more characterless, cold and inept.

I want to paint great things, I want to undo minds, I yearn to stretch into the abyss, to touch the living emptiness, to bring something radiantly new to the world—to bring life as it is back to existence as it merely seems to be… but when I draw all that comes out are cold lines and colourless disgust and human forms that look like mashed plastic and sausage meat. Something is wrong.

But is it? All art is ugly now. It just doesn’t matter. Or does it? It does, yes it does. And yet. What do they want? What do they actually want?

Tina comes over. I drag what I am supposed to be doing over what I am not supposed to be doing.

‘How’s it going?’ she asks, using a pleasant question about my general life in order to mask an unpleasant question about my specific task.

‘Fine Tiny, Tina.’

Her cheeks jerk—a nervous twitch she has—‘and the batch?’ Graham comes over, because his management-antennae has detected that someone in the city is not working to full potential.

‘Oh it’s slow going, taking longer than I thought, there are so many of them.’

‘Well, can you give us an approximate ETA?’ she asks. Graham juts his head forward to offset the unmanagerly tone of her question—too pleady Teeny—and give me a bit of the old scrutinising Squint of Authority.

‘Erm…’ I calculate how long this sub-moron task will take, and add 50%. They’re not happy with the answer, but have to accept it because, thanks to some earlier work-defying hex—I asked Tom the it guy to slow my computer down—they’re not quite sure of what is going on, and so have to accept my word.

They have to accept everything. They complain, or they put on the thin ‘knowing irony’ smile, or they pull the ‘someone should do a TV show about this place’ with the old ‘isn’t it awful!’ eyes-rolled-to-heaven. Yes, they complain, they all complain, but the complaint is built on a bedrock of acceptance. They often say to each other ‘you’re insane!’ or ‘you’re mad!’ and everyone smiles. When I say it, nobody smiles. When I say ‘you’re insane,’ it’s like I’ve taken a skull out of my rucksack and tried to photocopy it.

9:45. It is already another day of erecting barricades and sheltering from the poisonous arrows of many evils. ‘Please, no need to explain’? or ‘No need to pin me squirming in anguish to the walls of your empty heart for thirty minutes when you could just get to the point’? I often want to use the latter.

10:00. My empty stomach is having a strange effect on my attention. I am getting abnormally preoccupied with triangles of light and whassername’s legs—I still don’t know her name, the girl that works on the other side of my office, let’s call her Tuesday—she’s extremely attractive, wears short dresses and is usually barefoot. Everywhere she goes she trails the mournful, sexually-frustrated stares of the largely male workforce around with the pristine rotating orbs of her buttocks. Bristly, boozy Gavin next to me is, as usual, fretting into his phone (catchphrase: ‘I worry about what day it is’). He’s not overly concerned with Tuesday’s bottom because he’s worrying about the fact that it’s Thursday, and also he regularly visits prostitutes during his lunch hour, as he explained to me, pissed off his face one evening. He calls himself a ‘punter’ and says that he is addicted to ‘punting,’ new words for me, as is ‘retroactive,’ which is the curious adjective he uses to describe the accumulation of sorrow in his life. I suppose he uses it because he’s in the sales department, like Tom and Luke are always referring to their wives and girlfriends as ‘human units, female class’ and their relationships as ‘non-compliant,’ or ‘buggy,’ or ‘legacy.’ I try to use fancy words to describe my relationships, but can’t think of anything other than ‘shameful,’ ‘abortive’ and… ‘not’.

10:15. Made it. Fifteen minutes of freedom. I say freedom, but the first thing I do is check my emails, as I do thirty or forty times a day. I break the spell of the inbox by walking over to Harold, big square Harold in his comfy cardie, with his comfy mind in his big square head. He’s one of life’s meek losers, afraid of small-talk and young people and answering the phone and all sentences that begin ‘Harold…’ make him expect the worst. He collects classical longplayers which he hides in his bag—why I’m not sure, perhaps he’s been mocked for it in the past, or maybe he intuits that the Busch quartet are out of place in this thumping florescent realm—and then he furtively shows me the corner of the record, as if he’s scored some uncut cocaine. He loves radios too, and pumps, and air-conditioning systems, and boilers. At his engineering school he was once forced to go to the National Gallery to balance his technical education with ‘art appreciation,’ and he and his friends had spent the whole trip trying to work out how the state-of-the-art air-conditioning system there worked, huddled between the Caravaggios studying a cooling duct. For Harold the death of culture is the death of engines and all things which you can no longer take apart and fix yourself.

He also likes wearing women’s clothes. Again a public house provided the backdrop to a surprising confession of a colleague’s sex life. I don’t like the pub, actually, but if it weren’t for alcohol I would never learn that Gavin is addicted to pros and Alexis is unloved and Harold here secretly raids his wife’s wardrobe of a Sunday afternoon while she’s at her mother’s, prances around their flat for two hours exactly, returns everything as was and then steels himself for a weekly sexual encounter that more closely resembles a wrestling match.

‘She’s very competitive,’ he told me. ‘Even in bed. Especially in bed. It’s not really sex, it’s… it’s hard work. She usually likes me to take a few whiskeys first, and she has some, and then she, you know, she wants me to bang her up against a wall, and her eyes are, they kind of, they’re lolling around her head and her tongue darts in—and, it’s very stressful, because she’s barking instructions at me “harder, no, not there, okay now slowly and don’t look at me like that Harold…” and, I never really know if she enjoys it, we don’t talk about it, but I don’t think so, I don’t think we really like each other, but then who does? I don’t know. Discuss!’

10:30. I return to my desk and gaze again out the window. The rain has stopped and Seven Dials is ablaze with frigid sunlight. Dave Cardwell, guitarist from The Spin Men, is on the roof of his flat over the road, wearing a leopard-skin dressing grown and neon green underpants. He smokes a cigarette, flicks it over the edge of the terrace and walks back in.

11:00. I’m starting to smell of carbolic acid and off bread. The purge seems to be working, at least if noxious bodily odours, foul smelling breath, feeling hungover and a sensation that my brain is swelling behind my eyeballs are good signs, which I believe they are. Something to do with that middle-class bogeyman, toxins. I go to the toilet and am delighted to see that I look god-awful.

I stagger over to Tina’s desk and tell her I feel dreadful. I don’t feel middle-class at all.

‘You look dreadful.’

My inner saboteur, I mean the one that works for me, tenses up in expectation.

‘I think I might need to go home, get some sleep.’

‘Yes, you do that,’ she says, ‘you can continue with the conversions on Monday.’

I have to suppress a skip as the gates of heaven open up before me and a Soho-style flashing-bulb sign, pink and yellow, materialises above the stairwell, with an arrow pointing down to ‘liberation.’ My body slumps out, but my mind is on its knees, shaking skinny fists of glory to the sky.

Is work really this bad? Since leaving ‘education’ I have filled supermarket shelves, washed up restaurant plates, cleaned veterinary kennels, scrubbed ink from factory sinks, ‘guarded’ a motorway being built, plucked turkeys, packed apples, picked tomatoes and French beans, entered data, massaged spreadsheets, sold executive hospitality packages for Royal Ascot and now—what am I doing? I honestly don’t know, but it fits right alongside these other activities, and it fits right alongside the worklife of the world. The happy people, the worthy ones, fulfilled and driven, excavating Anglo-Saxon longships and designing surgical instruments and teaching orphans to code and running gourmet peanut bars—are a cigarette paper thin meniscus floating on a vast stagnant lake of boredom (known officially as ‘disengagement’), torment (known officially as ‘active disengagement’) and illusory duty (known officially as ‘productivity’). Down here where things actually get done, I have never seen anyone joyous at work because of work. Joy is an embarrassment in the workplace; it’s even more out of place than death.

And yet people willingly go. When they can’t work, when they have to stay at home, they complain that they’re bored. They can’t think of anything better to do than admin.

I stumble out of the zone of evil and instantly feel better, in my heart at least. My body needs a quiet room, ideally on the moon.

You have been reading the opening pages to Drowning is Fine…

Angry. Funny. Nightmarish. ArseHole-ish. Painful and sad …a tremendously smart, darkly comic, and surprisingly moving tale of life in today’s London. It will definitely get your head spinning. You may even discover it’s your own life in print…

Terry Gilliam

Other Reader Reviews…

…brutally honest, funny, bleak, painful and has a clear ring of truth about it …I literally can't think of any other writer living today who understands these times with the same clarity as Darren Allen. - Amazon Review (Tom Fryer)

…bloody good …the last forty pages or so are utterly brilliant - Goodreads review (‘Derek James Baldwin’)

For all his faults, Hickman [Daniel, the protagonist] is a modern-day Blakeian mystic in a culture where this can never mean anything outside the dubious romance of self-sabotage and self-destruction, hence why Daniel’s arseholish nature rises to the fore in a novel whose conventional form only reanimates the ghost of [our] highest values. - Steve Mitchelmore (This Space: read his full review here)

I think it’s a fucking masterpiece. It’s everything I look for and long for in a novel, and so rarely find. It’s magical, it’s Art with a capital A. It's already leapt into my Holy of Holies category of beloved books. - Email (‘Jeanne’)

I loved it. I’d pretty much given up on modern novels, finding them strangely blank. - Twitter comment (‘Garry’)

A genuine story about self-development and discovery about what’s what through mistakes, calamities, grim happenings, and confusion. Essentially - what we know as - REAL LIFE… I don’t know any other [book which has] made me have a few existential crises AND made me laugh hysterically. - Amazon review (‘Jack’)

…the insights and wisdom at the core of this book make it both moving and tragi-comic and lend it great depth, often lacking in modern literature. - Amazon Review (‘David Moore’)

One of the best I read about friendship, love, and existential questions. The novel is a blend of satirical, tragical, philosophical inquires to capture the absurdity of human predicament. - Goodreads review (‘Olesia Altynbaeva’)

Intensely evocative and gripping, transporting even. - Email (‘Yin’)

A tremendous novel which disturbed me so deeply that I laid awake for many hours upon its completion… - Reader Email (‘Ben’)

I thought nobody wrote books like this any more! takes a dive into the belly of the world with grace, humour and wisdom …shades of Celine, Hamsun, Bukowski and Miller. - Amazon review (‘N J.’)